CHAPTER VII

AMONG THE HEAD-HUNTERS

hen the Americans first came to the Philippines, most of the mountain country could be reached only on foot over dangerous trails. Very large tracts were unexplored, and the head-hunting tribes, who are found nowhere but in this northern part of Luzon, pillaged the neighbouring towns. A state of order has now been established, except in parts of Kalinga and Apayao.

The Mountain Province, the home of the head-hunters, includes the sub-provinces of Benguet, Lepanto, Amburayan, Bontoc, Ifugao, Kalinga and Apayao. The officers of the provinces are a governor, a secretary-treasurer, a supervisor in charge of the road and trail work and the construction of public buildings, and seven lieutenant governors. All these officers are appointed by the governor general. They live on horseback, undergo great hardships and also take great risks.The manners and customs of these head-hunt[Pg 271]ing tribes differ somewhat. Each one, for instance, has a different mode of treating the captured head when it is brought in, but all celebrate a successful hunt with a cañao, or festival. The Ifugaos place the head upon a stake and hold weird ceremonial dances around it, followed by speech making and the drinking of bubud, as they call their wine; afterward the skull of the victim is utilized as a household ornament. Venison and chicken are served at such feasts and the large fruit-eating bats, which are considered delicacies. If one of the tribe has been so unfortunate as to have his head taken, they berate the spirit at the funeral, "asking him why he had been careless enough to get himself killed."

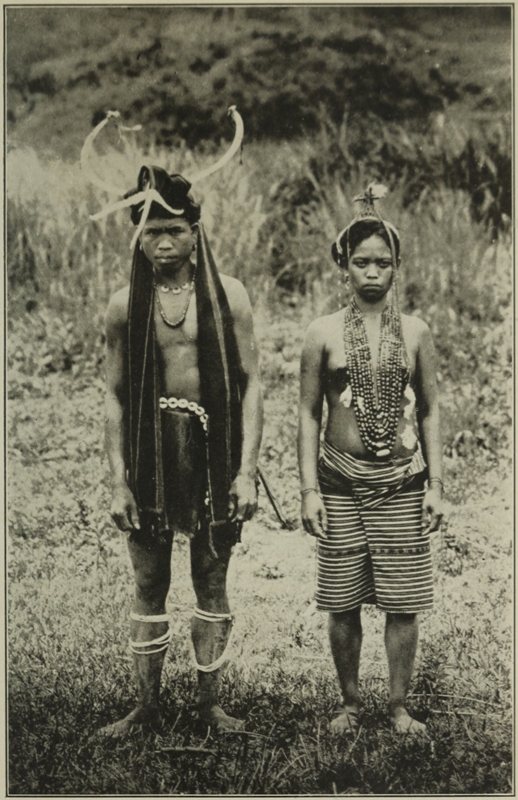

The most picturesque of the head-hunting tribes that my husband saw were the Kalingas, who are different from all other natives of Luzon. It is said that the Spaniards took fifteen hundred Moros into this part of the country more than a hundred years ago, so they may have founded this tribe. At all events, the Kalingas are superbly developed, tall and slight, some of the men having handsome and almost classical features.

Neither the men nor the women cut the hair, which, in the case of the men, is banged in[Pg 272] front and tied up with rags behind, some wearing nets to keep it out of their eyes. Although the women have abundant hair they use "switches," into which they stick beautiful feathers. The men also decorate themselves in the same way. On the back of the head they often wear little caps woven of beautifully stained rattan and covered with agate beads, and these are used as pockets in which small articles are carried. Great holes are pierced in the lobes of their ears, into which are thrust wooden ear plugs, with tufts of red and yellow worsted. Almost every Kalinga woman wears a pair of heavy brass ear ornaments and sometimes a solid piece of mother-of-pearl cut like a figure eight.

The Kalingas are particularly warlike, their very name meaning "enemy" or "stranger," and endeavours to bring them under government control were begun only a few years ago. There are still some rancherias which the lieutenant governor has not yet visited, as it seemed best to wait and bring the people to terms by peaceful means.

While we were enjoying ourselves at Baguio, the Secretary of War, Governor Forbes, Secretary Worcester, General Edwards, and my husband started north into the mountains to see[Pg 273] some of the strange tribes that were gathering from far and wide to meet the great Apo, or chief, as they called Secretary Dickinson. I give the account of the trip in my husband's own words:

On Saturday night, July 31st, after the Assembly baile, we motored to the docks and went aboard the transport Crook for the trip northward. We were made very comfortable on this big transport, with deck cabins, but we all slept on the open deck by preference and had a pleasant run till in the morning we were entering Subig Bay, a splendid vast harbour between great mountains, the narrow entrance guarded by Isola Grande. Here we landed and visited the batteries, and although it was a small island it was a stewing hot walk about it—especially as the Secretary sets a great pace—till a torrential shower came up and drove us to the commanding officer's house, where we had a bite of breakfast—and all the breakfasts at the posts which we have visited have been so good!

General Duvall had come up from Manila on his yacht Aguila, and on board of her we crossed the bay to Olongapo, where there is the present naval station. The great hulk of the famous floating dock Dewey was looming up there, just floated again after her mysterious[Pg 274] sinking which, even now, they do not seem to be able to explain.

The guard was out with the band, and the honours were paid and the marines paraded, but soon another severe tropical storm broke, and drove some of us back to the ship while the others went on to another breakfast at the Officers' Club. This storm suggested a typhoon, but there had been no warning from the Jesuit observatory at Manila, and so we rejoined the Crook out by Isola Grande and went to sea without fear.

This is the rainy and typhoon season but the warnings of severe storms are so carefully given that they have lost their terrors now-a-days; and this year, so far, there hasn't been a disturbance, much to our comfort, as it has permitted the carrying out of all our plans. It is a most unusual thing for such good weather to continue. The hot season is over, and this is called the intermediate, but it is the time of rains on this coast, the seasons differing slightly on the different coasts and in the different islands. So all that night we cruised up the coast through showers of rain and lightning, passing by Bolinao Light, which we had first sighted as we approached the Philippines.

Before daylight we stopped off Tagudin, and[Pg 275] through the darkness could be seen the dim shadow of land and mountains, and a light burning on the beach as a beacon. With dawn we saw a wonderful tropical shore develop before us, of low land fringed with palm, surrounded by beautiful mountain ranges, a tiny village on the beach, and a crowd of people gathered together. Soon a surf-boat put out and brought aboard the governors of the nearby provinces—Early and Gallman, brave, ready men, who have taken these wild people in hand and become demi-gods among them—and after a bite of breakfast we were all taken ashore through the surf, very handily, and the Secretary was welcomed by a native band and the chief men of the neighbourhood and crowds of half naked natives.

The Ilocanos of the northwest coast of Luzon are a fine, kindly race, but there had also come down from the interior a lot of small brown men to pack in our baggage, Bontoc Igorots, head-hunters and dog-eaters, of whom we were to see more in their own country. These little fellows at first seemed like dwarfs; but soon after, as we saw them better, they proved small but well formed and well nourished, strong, gentle little people. They ran forward and seized our packages and disappeared down the trail in[Pg 276] a wild, willing manner. Off they trotted while we were packed into carromatos, dragged by weedy, diminutive native horses, which are wonderfully powerful for their size. We went, after greeting the people, off down the trail, through the outskirts of Tagudin (we didn't go into the town, which was somewhat to one side, as there had been some cholera there), with its nipa houses of plaited grass, perched up above the ground, many decorated in honour of the occasion. We rattled along an excellent road (for we have certainly done wonders in road-building here), past paddy fields, where the slow carabao grazed with little children perched on their backs, past troops of natives, with their loads, standing alongside.

Governor General Forbes had made the most wonderful preparations for the trip. It was the first time that any American officials (only Insular officials previously) had gone in to these wild people, and of course the Secretary is the highest in rank that can visit the Islands since he is the one through whom the President governs the Philippines and the President can never come. The trip was unique and all the arrangements were extraordinary. For a new trail had been planned into the mountains but was not due to be done for eight months, and yet thou[Pg 277]sands of these wild men had been called in and helped to finish the road so much the more quickly (for we were the first party to pass over it, and some of the bridges had only been finished the night before we passed), eagerly and willingly, when they were told that the great Apo was coming in to visit them. Forbes had sent to Hongkong for some rick'shaws and had had men trained to pull and push them, but these had not stood the test well and we didn't have the need or the chance to use them; he also had had palanquin chairs brought over from China and men taught in a way to carry them, and these we did use on some of the steep descents. But we rode horses, excellent ones, from Forbes's own stable, almost all the way.

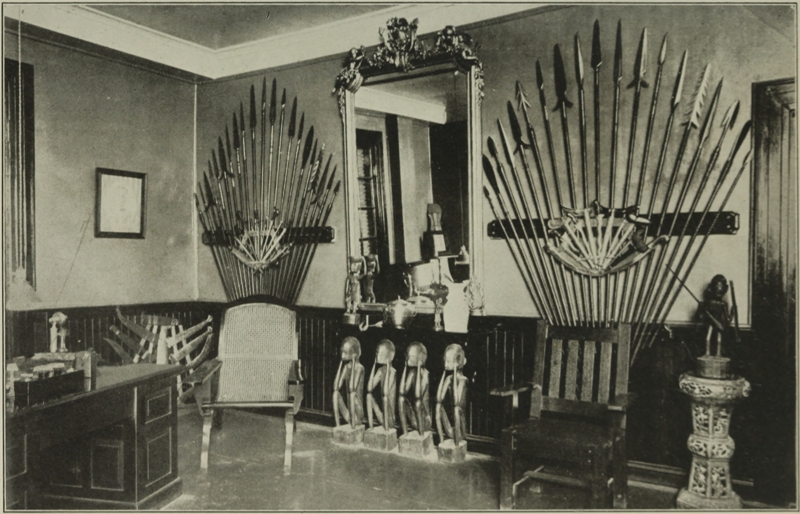

Every three kilometers, companies of Igorots and Ifugaos were stationed to act as cargadores and rush along the baggage by relays, and this they did with shouts and cheers as quickly as we traveled. Tiffin and breakfasts had been prepared all along the way. Every eventuality had been anticipated, and it was really too well done, for it made our traveling seem so easy that we had to think hard to realize into what out-of-the-way places we were going. A few days before it would have been necessary to work our way over the perpendicular old trails,[Pg 278] with difficulty finding bearers for our packs, and we would have been compelled to carry our own food, a severe trip and a hard undertaking. We went in absolutely unarmed and without escort, and yet nearly every native that we saw, after we reached the hills, carried his spear and head ax; but there wasn't a suggestion of danger. People were brought together on this occasion from different tribes who two years ago would have killed each other at sight, and yet to-day were dancing with each other.

We were accompanied by the governors of the sub-provinces as we passed through them, and an unarmed orderly and Sergeant Doyle, who had charge of Governor Forbes's horses, and generally by a shouting horde of natives. The Secretary proved a wonder; well mounted, as he was, he led on at a great pace, till it seemed a sort of endurance test. I was more than pleased to find that I stood it as I did, for we traveled four days out of the five for forty miles a day, and rode most of it a-horseback. I came out finally in much better form than when I went in.

And so, from the beach where we landed, the carromatos carried us across the low coast plain, over new bridges on which the inscriptions stated that they had been finished for the[Pg 279] passage of the Secretary and his party, and under triumphal arches made of bamboo which welcomed him; all the natives whom we passed saluted, and many wished to shake hands or only touch the hand as we passed, till we came into the foothills, and over them into a little village of nipa huts among the bamboo and tropical trees, where we found our horses waiting. Here we mounted and started off at a good pace over the well built road that trailed around cliff and crag as we worked into the mountains, a procession, a cavalcade, winding in and out. We traveled along the valley of a river, that later became a gorge with steep cliffs and precipitous sides; all the natives were out to greet the Secretary; and finally we came to a tiny village where we had a drink of refreshing cocoanut water, all the people standing about or hanging out of the windows of the simple houses, which looked very clean and neat. We trailed on along the narrow road, cut into the rock in many places, really a remarkable road, and up the gorge with the rushing river below us. The mountains rose high and opened up in lovely velvety greens, and shaded away into the blues of distance. We stopped at a little native rest house, above a ford in the river, where we found a luncheon prepared for us, but[Pg 280] it was a hurried luncheon, and on we went climbing a winding trail that zigzagged up the steep mountainside, through tropical tangle of bamboo and fern and great overhanging trees with trailing parasites—the ghost tree, the hard woods, and some with a beautiful mauve flower at the top that even Mr. Worcester couldn't tell me the name of (he said he had been so busy inventing names for the birds that he hadn't had time yet to find names for trees). And below the views opened up wider and more splendid, and range on range of mountains rose above each other, while the precipices grew deeper and more terrifying.

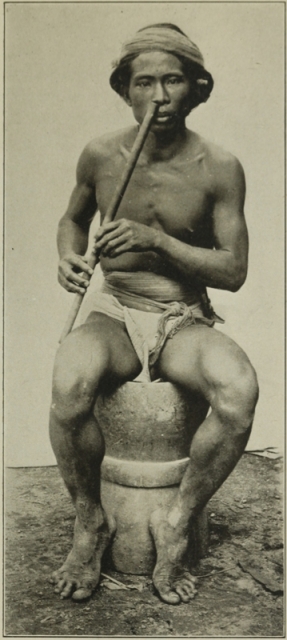

And suddenly, as we came to a turn in the trail, there appeared above us a most picturesque sight against the skyline, some Ifugao warriors, lithe, beautifully formed men, whose small size was lost in their symmetry, with spears in their hands, turbans of blue wrapped about their heads, and loin cloths of blue with touches of red and yellow in their streaming ends that hung like an apron before and like a tail behind; their handsome brown bodies like mahogany. They had belts made of round shells from which hung their bolos. These were the head men of a company of Ifugaos who had come this far to greet the party and they stood[Pg 281] so gracefully on the point above us; and around the turn we found the rest of the band, stunning looking fellows, standing at attention in line behind their lances, which were stuck in a row in the ground. Here we had another tiffin, while these warriors seized and scampered off with our luggage.

From this time on, as we traveled, we found reliefs of these picturesque people, waiting their turn at carrying, and then all would join in the procession, and shouting a cheer like American collegians, their war cry, they would rush on and frighten us to death with the risk of going over the steep places. Away off in the distance, reëchoing through the valleys, we could hear the cheers and cries, very musical, of others of our party as they traveled along. Soon we began to be greeted by the tom-toms of natives who had come out to honour the Secretary, and by their singing as we approached, and then they would dance round in a strange way as we passed on.

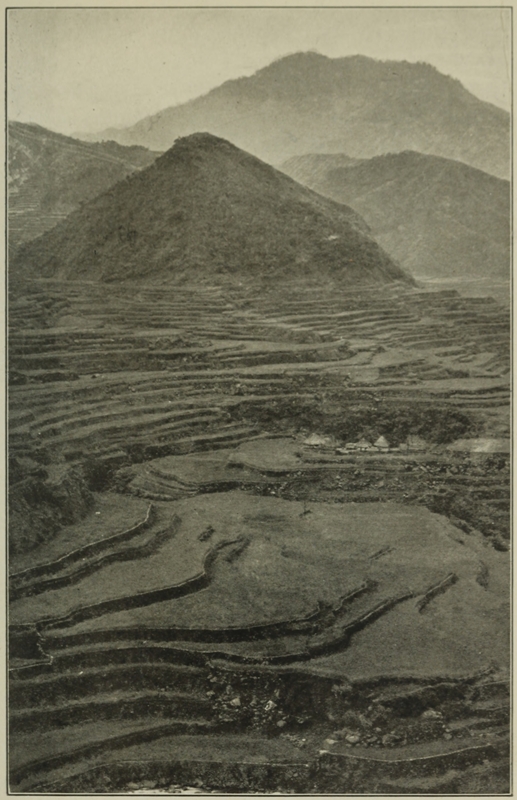

The Ifugaos had come to meet the Secretary from several days' journey away, mostly through Bontoc Igorot country, all armed, and yet there hadn't been a sign of trouble. And these Ifugaos, who two years ago were wild head-hunters, have been brought into wonderful[Pg 282] control by their governor, Gallman. There are some one hundred and twenty thousand of these picturesque people, among whom head-hunting is now nearly stamped out; though there are sporadic cases doubtless. These little savages, too, appear most gentle and tractable, most willing and laughing, in the rough tumbling of the trail; and they have proved very clever, for they were the builders of the roads over which we traveled (we were told that they could drill rock better than Americans, on a few months' practice, and that they have sat for a few days and watched Japanese bricklayers set brick, and then done it as well as the Japanese). But indeed their sementeras—their paddy fields—their terracing, which they have practised for hundreds of years, is the most wonderful in the world, and there is nothing even in Japan to compare with their work of this kind. Their great game of head-hunting has taught them cleverness, and they are full of snap and go.

The Ifugao is a great talker and has all the gestures of an orator. When he begins a speech he first gives a long call to attract attention, then climbs a stand fifteen feet high by means of a ladder. He generally begins his remarks by stating that he is a very rich man, and goes [Pg 283] on to praise himself and his tribe, and at the end of his harangue he often himself leads off in the applause by loudly clapping his hands. He has become a fine rifleman and is a fearless fighter. In clout, coat and cap, and a belt of ammunition, with legs bare, he travels incredible distances and makes a good constabulary soldier. The Governor General is anxious to form them into a militia, but they lose their grip, we were told, when they are taken down from the hills to the plain.

CONSTABULARY SOLDIERS.

CONSTABULARY SOLDIERS. When finally we reached the plateau and had crossed a river bed we were met by the people of the village of Cervantes—many girls in gay dress riding astride on their midget ponies, and men and boys on their rugged little mounts. These escorted the party under the triumphal arches into the grass streets of the pretty village, where the simple public buildings were decorated, and the local band played, till we finally were taken to the houses where we were to spend the night, the Secretary and the Governor and Clark and myself going to the Lieutenant Governor's. He was married to a Filipina wife. And here I must say that we met several of these Filipina wives of white men, and they had most perfect manners and self possession and real grace (and this one was a good cook). The house was a best class native house and more comfortable than we had anticipated, though there were sounds and smells that rather disturbed us. There was a reception and baile at the municipal building in the evening, where we had to go and dance a rigodon, each partnered off with some dainty little Filipina lady. And then we did hurry home to rest, for we had been up since half after four[Pg 285] that morning and were to start next morning a little after five.

The next day's trail was very fine, for we started off over a river which we crossed on a flying bridge, a swinging car on a cable, while the horses were forded; and then we had splendid but slow climbing up the gorge of one river after another, coasting the mountainside, where we could see the mark of the trail many miles ahead above us and part of our procession trailing along in single file or rushing along with distant shout, as the little willing native cargadores carried their loads up and up. Above us rose Mount Data, with its mysterious waterfall that seems to come right out of its peak, and clouds circled about us, and below the valleys streaked away into the distance and the ranges rose higher and higher, and the play of light and shadow was beautiful on the greens and grays and browns and blues of the distances. We began to see rancherias, the native villages, perched up on the hills, the thatched roofs like haystacks, with blue smoke at times coming through; and paddy fields began to climb the upper valleys in their terraces, with the pale green rice, and fringes of the banana palm of which the hemp is made. In places the red croton was planted on the terraces for luck,[Pg 286] and in the ravines which we crossed there were cascading falls and pools.

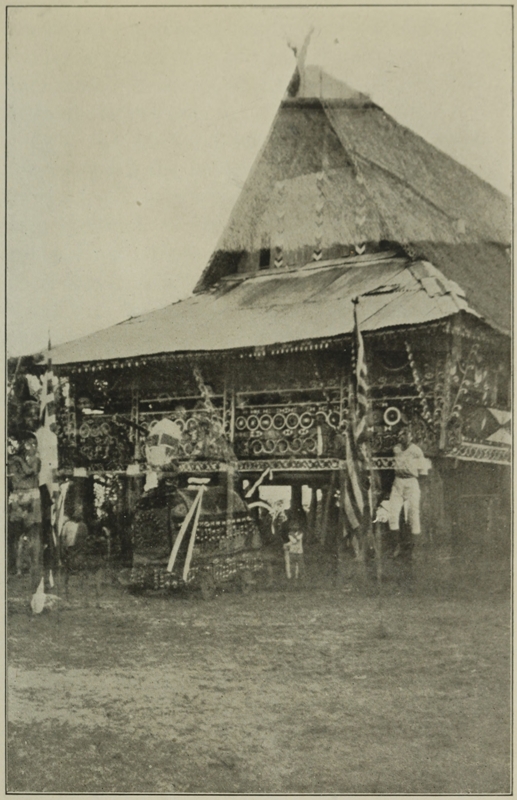

We rose higher and higher over another range, and at the tip-top of the trail another group of Igorots were dancing and playing their tom-toms as we passed, and rushed alongside to touch fingers. Soon we passed through a village built in a stony gorge where a river ran down. The houses consisted of conical thatched roofs supported on four wooden piers with ladders leading up into the roofs where the people lived. The foundations were terraced in stone and the paths were stone-terrace, and it all looked very neat and clean. On our way back we stopped for tiffin at this same village and had the women come and show us how they weave, for it was a place famed for its weaving. This time our tiffin was farther on, at a rest-house with a splendid view, and it had been laid out so prettily with temporary flower beds and bamboo arches. The Belgian priest from a town nearby had come to join us at luncheon, and although he spoke no English I had a pleasant time with him in French, for he proved to be a sort of relative of our cousins the de Buisserets; his name was Padre Sepulchre, one of a band of Belgians belonging to no order but educated highly for missionary [Pg 287] priesthood, who have been sent out, since our occupation, by the Pope, and many of whom are rich and gentlemen born. This one had already in two years spent some twenty thousand dollars gold of his own money in his town. Another such missionary we met at Bontoc, and several at other places, and all are said to do good work.

RICE TERRACES.

RICE TERRACES. So we trailed all day, till toward half after five we turned a point and came to Bontoc, after a procession of natives had come streaming out some miles up the gorge to meet the party. Bontoc is the capital of the Mountain Province and was the goal of our journey.

The native town is very dirty and is acknowledged to be one of the worst of the native [Pg 289] villages; in the more savage places the towns are said to be cleaner. We walked through it, where the terraced stone walks pass by stone pits where the pigs wallow, and by thatched houses which have no exit for the smoke and so are filthy and in dreadful condition. We saw the communal shacks in which the unmarried and widowed members live with their peculiar rights, and the sties where the old men resort to talk, and we stood outside the wretched place where the skulls are kept, and some heads, all black and smoked, were brought out in a basket from the secret recesses for us to see.

IFUGAO COUPLE.

IFUGAO COUPLE. Into Bontoc for this great occasion had been brought warriors and women from the Kalingas and Ifugaos, with Igorots from about, some from a distance of several days' travel; and for the first time these warring tribes, who only two years before were taking each other's heads,[Pg 290] came peacefully together, and watched each other with as much interest as they watched us.

The adventures of the American lieutenant governors read like romances, and here they were before us with their following: the Kalingas more dangerous and warlike than the Ifugaos, and the Ifugaos more picturesque and interesting than the Igorots, and all together making a never-to-be-forgotten scene.

There were, too, several small companies of native constabulary, for these hill men make splendid soldiers and take great pride in their arms and uniform, and have proved loyal to the death. All the different tribes and the constabulary had turned out to receive the Secretary, and it was a vociferous and noisy yelling crowd that streamed about in irregular procession. We were, some of us, taken to a government house that was comfortable, and took our meals at a club which the officials have built and which is quite pathetically complete, and that evening we did little before turning in—the first evening since we had landed in the Islands when we were able to turn in at a reasonable hour with the prospect of sleeping as late as we pleased next day.

Next day was a day of festivities, a cañao, for from morning till night there was dancing[Pg 291] by these fantastic peoples, whom so few white men have ever seen. We were waked early enough, alas! by the ganzas—the tom-toms—and there were parades of the different tribes through the town. A small grandstand had been erected in the plaza, and there we stood with the Secretary and the few white teachers and the missionaries from about, while the procession was reviewed.

The constabulary came first, dressed only in loin cloths of different colours below the waist, but with the regulation khaki uniform blouse and cap above. They are officered by Americans and a few natives, and are most military, notwithstanding the strange appearance of their bare legs. Some companies were very well drilled, and they gave exhibitions of different manuals as well as any regular white soldiers might have done.

The wild Kalingas came past next, most picturesque, with their feather headdresses of red and yellow, and spears and head axes, and their brightly coloured loin cloths, and the women in scant but gay garments, and not at all ashamed in their nakedness. And these gave their characteristic dances, with outstretched arms, hopping and prancing about in a circle, all the time looking down into the center of the[Pg 292] circle about which they dance (where the head of the decapitated is supposed to be). There were innumerable tom-toms, which they play with variations, so as to make much rhythm and movement, and the women joined in the dancing, more moderately, some with big cigars in their mouths and looking extremely indifferent. Then, when they danced in a circle, some would prance into the center with shield and ax and pretend attacks upon each other, and leap about and grow excited; and this sort of thing they kept up all day (and part of the night, too) off and on.[21][Pg 293]

The Ifugaos followed and passed by, and gave their dances, which are the same with a difference, but each was ended with a mighty shout, after which one of the head men would step forward and deliver a rattling speech, and they greeted the Secretary variously but cordially—for they like our American rule, indeed, they have never had any other, for the Spaniards never attempted to come in and control them.

IFUGAO HEAD DANCE.

IFUGAO HEAD DANCE. Then the Bontoc Igorots followed and gave exhibitions with noisy demonstrations, and two presidentes, or chiefs, who six months before were trying to kill each other, danced and pranced together, while the tom-toms beat and others hopped and circled round. Most of the men were tattooed, each tribe in its own peculiar manner, certain marks indicating that their bearer had killed his man and taken a head—some bore marks of many heads; one man dancing was known to have taken seventeen. Many of the women, too, were tattooed with a feather-like pattern.

And so the dances went on. In some the participants postured fighting and then represented wounded men; in others all were head men together; some were rapid in motion, some slow, but all had real grace, that grace of the wild man; and all were finely formed and well-nourished and healthy looking. When the dancing was over, the groups of savages in their fantastic dress squatting around the plaza behind their spears stuck in the ground, with bolo and head-ax and tom-tom, and the women standing about, made a wonderful scene.

After the dances and speeches the head men came up to the Secretary and handed him weapons as gifts, sometimes their own, with [Pg 295] which they had often fought. Mr. Dickinson, of course, received the chiefs and the head men and women afterward, and presented them with shells and blankets and plumes in return. The bartering among them was rather amusing, as they tried to exchange what they had received and didn't want.

WEAPONS OF THE WILD TRIBES.

WEAPONS OF THE WILD TRIBES. We started out at daylight next morning and hiked back by the same trail; but the views seemed finer in their repetition than even when we first passed through them. We had had most superb weather, although it was the rainy season, and had enjoyed the grand panoramas to the full; but the last afternoon it came on to pour down in torrents, which we enjoyed too as an experience, for we came safely to Tagudin, where the people and the band joined in sending us off, as they had received us, and we were safely taken out through quite a heavy surf and put on board the Coast Guard boat Negros, and had a glass with ice in it again.

[Pg 296]

CHAPTER VIII

INSPECTING WITH THE SECRETARY OF WAR

ugust thirteenth is a holiday in the Philippine Islands, for it is "Occupation Day," the anniversary of the fall of Manila and its occupation by the American army. The special event is a "camp fire" in the evening at the theater, when the Philippine war veterans gather together and have addresses and refreshments. After a dinner with Tom Anderson at the Army and Navy Club, with its picturesque quarters in an old palace, intramuros, we attended this performance, sitting in the Governor's box and listening to the happy self-laudation of the "veterans," who all wore the blue shirt and khaki of war times.

It was toward midnight when we finally left and went out to our vessel, for we were off for a trip among the southern islands on the cable steamer Rizal. We sailed by the light of a full moon, and for a while had a merry bobbery of it outside, after passing Corregidor. Soon, though, we turned a point and had the monsoon[Pg 297] following. In the morning we woke to find ourselves steaming past the fine scenery of southern Luzon, with the volcano of Taal in the distance. Several times during the Spanish occupation this volcano dealt death and destruction, and as late as 1911 it claimed many victims.Our first landing place was at Kotta, on Luzon, where we started ashore in a small launch. It was a beautiful river of palms, but our boat got stuck in the mud and we were delayed. We finally reached the shore and were put into automobiles. Then it was that I began to feel as if I had joined a circus parade. Escorted by bands and soldiers, our motors moved slowly along the streets. Everywhere people lined the way, while the windows of the houses fairly dripped with heads.

We passed many little villages that looked prosperous, and processions of carts, showing that the people were active and busy. The road ran over picturesque bridges, for part of it was an old Spanish trail rejuvenated. At all the villages they had made preparations to receive the Secretary, bands were out, the children stood by the roadside and waved, and the women stood in rows to greet us. The municipal buildings were decorated, the piazzas hung with festoons and lanterns. They all[Pg 298] wanted to give us comida and let off speeches, but it was impossible to live through such hospitalities, so we only halted at each place a few minutes to shake hands.

The stop for the night was Lucena, the home of Mr. Quezon, Philippine Commissioner to the United States Congress. He traveled with us, and we found him very attractive. The general opinion was that Quezon, Legarda, and Osmeña were "playing to the gallery" for political capital, but at the same time they were supporting our administration. It is a good deal like some of our friends in Congress, who make speeches along lines that they know are absolutely untenable.

After climbing into a bandstand, where we stood surrounded by people peering up at us, flowery speeches began, demanding independence. They were the first of the kind we had heard. The Filipinos are good speakers and keen politicians. Among other remarks, an orator said: "Many things occur to my mind, each of which is important, but among them there is one which constitutes a fundamental question for the Filipinos and the Americans. It is a question that interests equally the people of the United States and the people of the Philippine Islands. It is a question of[Pg 299] life or death for our people, and it is a question also of justice, for the people of the United States. The fundamental question is evidently, gentlemen, the question of a political finality of my country....

"We are very grateful for your visit, Mr. Secretary, and we hope that the joy that we felt on your arrival may not be clouded, that it may not be tempered, but rather that it shall be heightened, by seeing in you a true interpretation of the desires of the Philippine people, hoping that on your return to the United States after your visit to the Philippine Islands, you will tell the truth as regards the aspirations of the Philippine people."

In answering, the Secretary talked about the different subjects of interest, such as the agricultural bank, land titles, etc. He continued:

"It is very gratifying to me, coming from America, and representing the Government in the position in which I stand, to hear such testimonials as you have given in regard to the men that America has sent to assist you in advancing your interests.... America has been careful to send men in whom confidence can be reposed according to their previous character; and I want to say to you further, that America[Pg 300] has given you here just as good government as she has given to her people at home.[22] In all established governments fair and just criticism is welcome and I shall not therefore bear any spirit that would be resentful of any just criticism.

"I shall be very glad while I am here to meet those who have the real welfare of the Islands at heart and the development of this country. I have many things to do and the time is comparatively short, but I shall endeavour so to conduct affairs as to be able to give audience to all law-abiding people who may desire to make any representations to me. I shall be at convenient periods here where I shall be accessible, and any communications which are addressed to me personally will receive proper consideration. Now that states in a general way the object of my visit and the disposition that I propose to make of my time while here. General Edwards, who is with me, as you know, is the Chief of the Insular Bureau. Certainly he, more than any other man in America, understands conditions in the Philippines, and his whole time, thought and mind are concentrated [Pg 301]upon the problems connected with your welfare, and he is working all the time to advance your interests. His familiarity with conditions from the time of America's occupation, the establishment of civil government, the settling of the various commercial questions that have arisen from time to time, make him the most effective champion for the Philippine interests in America, and he has not hesitated in Congress whenever your interests are at stake, to stand up and contend for your interests with vehemence that ought to make him eligible to all option as a Philippine citizen....

"You have there a brilliant representative (Mr. Quezon), who is capable of presenting your views and aspirations, and of enforcing your wishes with the most cogent arguments of which your cause is susceptible....

"Now as to immediate independence: we Americans understand by immediate, right away—to-day. Do you want us to get up and leave you now—to depart from your country? You would find yourselves surrounded by graver problems than have hitherto confronted you, if we should do so. I don't positively assert, but I suggest that you yourselves pause, and think whether you might not be reaching forth and grasping a fruit which, like the dead[Pg 302] sea fruit, would turn to ashes upon your lips."[23]

It was at Lucena that my husband and I went to Captain and Mrs. S.'s house for the night. We sat on the piazza by moonlight, among beautiful orchids, listening to the band playing in the distance, and gossiping. I was interested in the servant problem, and Mrs. S. had much to tell me that was new.

"Our native servants would much rather have a pleasant 'thank you' than a tip," she said; "if a tip is offered, the chances are that it will be refused, for the boys feel that they would do wrong to accept it. They are very keen, though, about their aguinaldos—presents—at Christmas. Every native who has done a hand's turn for me during the year will turn up Christmas Day to wish me a feliz Pasquas, and I am expected to give him a present. My whole day is for my servants and their children, who seem to multiply at that time. When I asked my cochero, 'Lucio, how many niños have you?' he answered, 'Eleven, señora.' 'But how many under fourteen, Lucio?' 'Eleven, señora!' He wanted all the presents that he could get," she laughed.

"But if they don't take tips, do they get good wages?" I asked.

[Pg 303]

"Not according to American ideas. A Filipino boy will work for small pay, and stay a long time, in a cheerful home atmosphere. They are good servants, too," she continued, "if you take the trouble to train them. I trained a green boy to be a good cook by taking an American cook book and translating it into Spanish. They have a great reverence for books, and that boy thought he was very scientific. I've had him many years. We loaned him money to build his hut near us. He was a year paying it off, but he paid off every cent. Now he has four children for Christmas gifts. When I went away on a visit, he asked me to bring him a gold watch from America. So many years with us gave him that privilege. As we were gone some time I think he feared we might not return, so he wrote us a letter." Seeing my interest, she got the letter and read it to me:

"My Dear Sir Capt.:

"In accompany the great respect to you would express at the bottom. It is a long time since our separation and I'm hardly to forget you because I have had recognized you as a best master of maine. So I remit best regard to you and Mrs. and how you were getting along both, [Pg 304]and if you wish to known my condition, why, I'm well as ever.

"Sir Capt. If you will need me to cook for Mrs. why I'll be with you as soon as I can find some money.

"Please Sir Capt.

"Will you answer this letter for me?

"Very respectfully

"Yours, Pedro."

"Will you answer this letter for me?

"Very respectfully

"Yours, Pedro."

"On returning from the United States I took Pedro back," Mrs. S. went on, "but I found I needed extra house boys. The first who presented himself was Antonio, aged seventeen. He was a very serious, hard-working boy, whose only other service had been a year on an inter-island merchant ship. I took him at once, for servants from boats are usually well trained. He turned out well, and in a few months asked if he could send for his little brother to be second boy to help him. I said he could, so in due time Crispin smilingly presented himself. No questions passed as to salary or work. He was installed on any terms that suited me. A few weeks later, Antonio asked if he could bring his cousin in just to learn the work, so that he could find a place. I consented, and in time came Sacarius, gentle and self-effacing, and [Pg 305]apparently intent on learning, and always handy and useful. Again a favour was asked, this time that the father of Antonio might come as a visitor for a three weeks' stay. He was very old, would not eat in my house, only sleep in the servants' room, so again I consented. Father must have already been on his way, permission taken for granted, for his arrival was almost simultaneous. I found him sitting in my kitchen in very new and very clean white clothes, the saintliest old tao, with no teeth, white hair, and a perpetual smile. He rose and bowed low to me, but he couldn't speak Spanish or English, so called his son to him to salute me for him formally. I returned it and made him welcome to my house. He bade them tell me he had journeyed far to tell me of his gratitude for my goodness to his family and that he had such confienza in me that he had instructed his sons never to leave me. The old fellow enjoyed himself thoroughly, and spent so much of his son's money that Antonio shipped him home in a week."

"Are they spoiled by living with Americans?"

"Yes, but it shows most in their clothes. Antonio dresses almost as well as his master," laughed Mrs. S. "But he does not attempt to work in his best clothes, wearing the regula[Pg 306]tion muchacho costume without objection, even though some of the army officers' muchachos are allowed to dress like fashion plates, and clatter round the polished floors in their russet shoes. A muchacho will spend his whole month's pay for a single pair of American russet shoes. They love russet, and the shoe stores flourish in consequence."

"How about their amusements?" I inquired.

"Whenever they can get off they go to baseball games and the movies. The little girls wear American-made store dresses now, and great bunches of ribbon in their hair, white shoes, and silk stockings. Some families who in the early days had hardly a rag on their backs now own motors. I don't believe you could force independence on them! The señoritas trip home from normal school with their high-heeled American pumps, and paint enough on their faces to qualify for Broadway. The poor children have to swelter in knitted socks, knitted hoods, and knitted sweaters, just because they come from America. Filipino children are wonderful, though—they never cry unless they are ill. They are allowed absurd liberty, but they don't seem to get spoiled. The Filipina women love white children intensely; the fair[Pg 307] skins seem to charm them, and they really can't resist kissing a blond child."

We certainly enjoyed our stay at Lucena. Mrs. S.'s house was so clean and homelike, with its pretty dining room and its broad veranda, and the big shower bath which felt so refreshing. We went to sleep that night watching the palm leaves waving in the moonlight.

In the early morning we all got into automobiles again and ran over fine roads built since the American occupation. We left the China Sea and crossed the island to the Pacific, climbing a wonderful tropical mountain, where, by the way, we nearly backed off a precipice because our brakes refused to work, and we frightened a horse as we whizzed on to Antimonan. The churches here had towers something like Chinese pagodas, and the big lamps inside were covered with Mexican silver. All these island towns have a presidente and a board of governors, called consejales, and each province has a governor.

Manila hemp is one of the principal products of this prosperous province, and it is chiefly used to make rope. The plant from which this hemp is made looks very much like a banana plant. The stalk is stripped and only the tough fibers are used. They employ the cocoanut a[Pg 308] good deal to make oil, which is obtained from the dried meat, called copra. They had a procession of their products here at Antimonan, which was very interesting.

The hemp and cigar importations were first carried on by Salem captains in the fifties. The great American shipping firm in those days was Russell, Sturgis, Oliphant and Company. The Philippines were out of the line of travel, however, and few people went there except for trade. In fact, as far as I know, only one book was written by an American about the islands before the American occupation.

On the Rizal next morning, when I looked out of my porthole at dawn, it seemed to me as if I were gazing at an exquisite Turner painting. Mount Mayon[24] was standing there majestically, superb in its cloak of silver mist, which changed to fiery red. It is the most beautiful mountain in the world, more perfect in outline than Fuji. Mrs. Dickinson was so inspired by its beauty that she wrote a poem, a stanza of which I give:

"Mount Mayon, in lonely grandeur,

Rises from a sea of flame,

Type of bold, aggressive manhood,

[Pg 309]Lifting high a famous name

'Bove the conflict of endeavour

Ranging round its earthly base,

Where heartache and failure ever

Stand hand-clasped face to face."

Rises from a sea of flame,

Type of bold, aggressive manhood,

[Pg 309]Lifting high a famous name

'Bove the conflict of endeavour

Ranging round its earthly base,

Where heartache and failure ever

Stand hand-clasped face to face."

LANDING AT TOBACO.

LANDING AT TOBACO. When our party dispersed for dinner L. and I were "farmed out" to the superintendent of schools, Mr. Calkins. The houses built for Americans were all of wood with broad piazzas, much like summer cottages at home, with the[Pg 310] hall in which we dined in the center and the bedrooms leading off it.

So much has been written about the schools and the wonders in education in the Philippines that I shall not try to enlarge on this interesting theme, other than to add my tribute to the government and the teachers, and also to the people who are wise enough to take advantage of the opportunities offered. Each little Juan and Maria, with their desire to learn, may soon put to shame little John and Mary, if the latter are not careful.

"It has not been a fad with them, as we feared it would be," one of the teachers told me; "they have stuck to it. Many grown-ups in the family make real sacrifices to keep their juniors in school. My little Filipina dressmaker is educating all her sister's children and sending her brother to the law school. At first, too, we feared there would only be a desire to learn English and the higher branches, but with a very little urging they are learning domestic science and the trades, showing that they have a mind for practical matters after all."

I begged her to tell me more about the natives, since she understood the people so well, and what she said is worth repeating.[Pg 311]

"Even in his grief the Filipino is a cheerful creature," she began; "curiously enough, too, a death in the family is an occasion for general and prolonged festivities. An orchestra is hired for as many days as the wealth of the family permits, and a banquet is spread continuously at which all are welcome, even former enemies of the deceased. Strangers from the street can come; I've often wondered if the beggars imposed on this custom, but there are very few of them, and they seem to respect it. The music drones on day after day. Sometimes only one instrument will be left, the other players going out to smoke, or eat, or rest; but they reassemble from time to time and keep it going. There is always much dancing, for the natives are great dancers and were not the last to learn the one-step and hesitation. Even in their heel-less slippers they are very graceful. Of course masses are said, for they firmly believe that these will take their departed to heaven. With this belief they are so happy, knowing the dear one is better off in heaven than here, that Chopin's funeral march is quickly turned into waltz time, and the fiesta waxes merry!

"In Spanish times each district had its band, which always played at the church festivals.[Pg 312] Each church had its patron saint, and there was always a saint's day fiesta going on in some district. In the churchyard booths were spread as at our country fairs. Everything from toys to all kinds of chance games, of which they are so fond, was sold. The band played continuously and the people came in crowds. The Americans have catered to this spirit in the yearly carnival which is given every February. This carnival is more than a fiesta, though, for it is also an exhibition of their produce and handiwork. Their hats have always been famous, as has their needlework, and under American encouragement the basket-work exhibit has become one of the finest in the world. Some hemp baskets, woven in colours, look as if they were made of lustrous silk. I can't say which I like best, the finest of our Alaskan Indian, or Apache, or Filipino baskets. Their shell work is lovely, too, and their buttons are coming into the world's market for the first time.

"The Filipinos are also learning at the School of Arts and Trades to carve their magnificent woods most skilfully, and are making furniture which will soon be coming to the States. In the early days a few Chinamen had the monopoly of furniture carving and making. They copied the very ornate pieces brought to[Pg 313] Manila by the Spaniards from Spain and France in the native mahogany called nara, and in a harder and very beautiful wood called acle, or in a still harder one known as camagon, a native ebony. American women soon began to search the second-hand stores and pawn shops for the originals, and had them polished and restored at Bilibid Prison. The expense, considering, was small. A single-piece-top dining table of solid mahogany is often nearly eight feet in diameter and two or three inches thick."

Another of the teachers told me something of her experiences in the early days, when she went out with her father, who was one of the first American army officers there.

"When we landed we lived in an old Spanish palace," she said, "which of course we proceeded to clean. That was the first thing all Americans did on landing. We took eleven army dump-cart loads from the palace of every kind of dirt conceivable. Then we began washing windows and mirrors and lamps, which I am sure had never been touched with water before. The servants were so amazed that they were of very little use. They were mostly Chinese, and had never seen white women work before. The sight of such energy staggered[Pg 314] them. Just when we got things running smoothly, father was called home, and our cleaned house fell to his successor's wife, who wept and said she had never been put in such a dirty place.

"It was after this that my real adventures began. Father McKimmon was opening public schools, and wanted English taught. So he went among the army girls and just begged us to give up a few of our good times and do some of this work. I didn't see how I could teach people when I didn't know their language, but he explained how simple it would be, and we could learn Spanish at the same time.

"It was fun to work with the Spanish nuns. They were so interested in us, and their quaint, old-fashioned methods with the children amused me constantly. Arms were always folded when they rose to recite, and it was always 'Servidor de usted'—at your service—before they could sit down. The nuns soon became pupils of ours, too. When the Spanish prisoners liberated by our men from the Filipinos were brought to Manila they were quartered in our school for a hospital. I never saw such starved wrecks. Many of them—young men—had no teeth left.

"More Americans were arriving on every transport, and a most delightful society was[Pg 315] forming of army and navy people, government officials, and naval officers of every nation, in addition to the original Spanish population and the small colonies of many countries. There were parties of all kinds, and as we trained our cooks into our own ways we ventured on dinner parties. I shall never forget the first dinner I went to that was cooked in Spanish style. There was every kind of wine I ever heard of, but no water. I wanted some, but it was not to be had. My host apologized for not having provided any, but no one dared drink the city supply. We sat down to table at nine and rose at twelve, and when the men joined us at one they were all much amazed that I made the move to go home.

"I left Manila to visit my brother in the provinces. Traveling in those days was very different from what it is now. After leaving the Manila-Dagupan Railroad there were no motors to go up the mountain; instead of that, I rode an ancient American horse till I was tired and burning with the sun. Then my brother put me in a bull cart, and I sat on the floor of that till the sun was preferable to the bumping. I arrived at four in the afternoon and was put down in an empty room with my trunk and a packing box. Being a good army[Pg 316] girl, that packing box had all the elements of comfort, but first there was cleaning to be done. My brother was the commanding officer in that town, his house being at the corner of the Plaza, and an outpost. So he sent me a police party—that is, ten native prisoners and an American sentry; they were armed with brooms and buckets. I said, 'Sentry, this room is very dirty. The Captain sent these men here to clean it for me.' 'Yes, mam,' said the sentry. 'Well,' I told him, 'I want the ceiling cleaned first, even the corners!' He turned to his gentle prisoners with 'Here, hombres, you shinny up that pole and limpia those corners!' He didn't know much Spanish, but limpia means clean, and is the one essential word. I soon unpacked my box and turned it into an organdie-draped dressing table, after out of it had come all that made the room livable.

"That night I was sleeping the sleep of the very tired when I was awakened by a blood-curdling shout, a gun was thrown to the floor, and a man's voice yelled for help. I simply froze—I couldn't move hand or foot. The voice was in the outpost guard room, just under my own. Of course, I was sure the whole guard was overpowered and being boloed. I waited for them to come to me as I lay there. Then[Pg 317] I heard a man's voice call from an upstairs window, 'What's the matter down there?' and the answer, 'Number Four had a nightmare, sir—thought there was a goat on his bunk.' Just as I was going to sleep again I threw out my hand in my restlessness, and to my horror, clasped it round a cold, shiny boa-constrictor. Every large house has one in the garret to keep down the rats. This time I gave the scream and sprang out of bed. But no snake was to be found, and I decided it must have been the bed post. But what a night that was!"

We reëmbarked at Legaspi and sailed on to the island of Samar, which is in the typhoon belt. Catbalogan is a town which has been visited by very severe typhoons and terrible plagues, but by very few people. It is a small place, far away and forgotten, but the island of Samar is where the massacre of the Ninth Infantry occurred—the massacre at Balangiga by the natives in 1902. There were triumphal arches of bamboo and flowers, and speeches in the town hall, Governor Forbes speaking in both English and Spanish. Afterward eight small boys and girls dressed in red, white and blue danced for us enchantingly the Charcca and the Jota, clicking their little heels and snapping[Pg 318] their little fingers in true Spanish style. Delicious sweetmeats were offered on the veranda, real native dishes, and we drank cocoanut milk and ate cocoanut candy, preserves, nuts and cakes. Two half-Chinese girls who spoke English took very good care of us.

As we left we looked out over the sea to the setting sun and watched a lonely fisherman standing on a rock throwing his net.

Next morning from the Rizal, we saw across a stretch of calm water the blue ranges of the mountains of Bohol. Native bancas glided silently about, and a straw-sailed boat drifted idly round the point, where the picturesque gray walls of the oldest Spanish fort in the Philippines stood guard. Its sentinel houses at the corners were all moss grown, and pretty pink flowers were breaking out of the crevices of the rocks.

We landed at Cebu, which is the oldest town in the Islands, and passed down a street lined with ancient houses whose second stories arcaded the sidewalk. They were all in good condition, in spite of their age, for they were built of the wonderful hard woods that last forever. In fact, Cebu has the look of a new and prosperous place, for there have been fires which burnt up many of the ramshackle houses[Pg 319] and gave a chance to widen the streets and replace the old structures with permanent looking buildings. The American government has done wonders in deepening the harbour and building a sea wall, behind which concrete warehouses are going up.

There was a scramble to a review near the barracks, then another scramble to a reception at the house of the colonel commanding—a very nice but hot occasion—and then still another scramble to the dedication of a really excellent schoolhouse.

A young priest took us to see the famous idol, the small black infant Christ. We went to the convent of the Dominicans near the church, and passed through its pretty, unkempt court, up a staircase with treads and handrail richly carved in a wood which was hard as iron, and black with age. It was handsome work, such as we had been looking for and hadn't seen before. In the sacristy, too, and the robing room, there were screens and paneling with richly detailed carvings. Passing down the galleries of the convent, where we could see some of the friars at work, we entered the special chapel where this holy image is kept. Several doors were taken off a rather gaudily gilded altar, until at last the little figure was revealed.[Pg 320] Its back was toward the room and it had to be carefully turned—a small, brown, wooden doll, all dressed in cloth of gold, and bejeweled like the Bambino of Rome. It is considered a most sacred and wonderful heaven-sent idol.[25]

As we had heard speeches by Filipinos and head hunters, I was curious to know what the Chinese would have to say, and that night there was an opportunity to find out, for we were invited to a dinner given by the Chinese merchants. I quote from the speech made by Mr. Alfonso Zarata Sy Cip, which was specially interesting:

"The Chinese have traded with these Islands since long before Confucius and Mencius," said Mr. Sy Cip; "and for centuries we have been coming here and assimilating with the Filipinos, and to-day we are deeply interested in the welfare of the country. The Chinese have been called a nation of traders, the Jews of the East, but we are more than traders. We are labourers, artisans, farmers, manufacturers, and producers.

[Pg 321]

"A very large percentage of the growth and development of the commerce and material interests of the Islands is due to the efforts of our countrymen.

"The infusion of Chinese blood has strengthened and improved the Filipino people.

"Chinese labour is recognized all over the world as the best cheap labour in existence. Since American occupation of these Islands you have excluded our labour from entering. Why? Not for the reason that it would tend to lower the standard of living among Filipino labourers, because the standard of living among Chinese labourers in the Philippines is higher than among the Filipino labourers. Hence the introduction of Chinese labourers would tend rather to improve conditions in this regard. You do not exclude him for the reason that he works for lower wages than the labourers of the country, because, on the contrary, the Chinese labourer in the Philippines receives higher wages than the native labourer, hence the introduction of Chinese labourers would tend rather to improve the condition of the native labourers as far as wages are concerned. You do not exclude him for the reason that he will not become assimilated with the natives of the country, because centuries of experience have[Pg 322] shown that Filipinos and Chinese do assimilate and readily amalgamate, and the result, as I have already said, is an improvement of the Filipino people. If you are excluding Chinese labourers from the Philippines because of political reasons then I confess such reasons, if they exist, have been carefully guarded as secrets from the public.

"Lack of room is not a reason for excluding Chinese labourers, nor is lack of need for their services. In the great island of Mindanao alone it is doubtful if five per cent of the tillable land is under cultivation, and in other places it is the same. A large part of the rice consumed in these Islands is imported from other countries, yet we have here the finest tropical climate in the world and the most productive soil. Let a sufficient number of Chinese labourers come into the Philippines and we will guarantee that in ten years we will be sending rice to the gates of Pekin and Tokyo."

Toward night we sailed on the Rizal from Cebu for the land of the Moros. Out in the Sulu Sea, one felt very near heaven when the sky turned hazy gray in the afterglow, and the distant islands mauve, only their peaks flaming like volcanoes from the hidden sun. Then the big stars came out, like Japanese lanterns, and[Pg 323] left a comet-like trail upon the dancing waters.

From their holes below the cabin boys, Ah Sing and Sing Song, would pop out like slim white mice with their long black pigtails, with little cot beds tucked under their arms which they would place in rows upon the deck. Ah Sing would say, "Cheih ko koe" (that will do), and Sing Song would answer, "Hsiao hsin" (be careful). Later, when the moon rose out of the sea and the Southern Cross appeared on the horizon, shadowy forms glided silently up the companionway. But the silence did not last. Some one would call to Sing Song in pidgin English:

"Boy! go catchy whiskey, Tansan; top side, talky man little more fat!" And some one else would say to Ah Sing,

"You fool boy, you catchy me one bath."

Ah Sing seemed to understand. He would wag his head and answer, "You good man, no talky all the time, makey me sick." And he would disappear.

At sight of a tall, genial man, the people in their cots would sing out, "Doctor Heiser's a friend of mine, a friend of mine, a friend of mine," etc. American judges, and Filipino congressmen and generals were of the company.[Pg 324] Occasionally a whisper, very often a giggle, sometimes a clinking of glasses, and good night kisses, were heard, and then the sand man closed our eyes.

[Pg 325]

A MORO DATO AND HIS WIFE, WITH A RETINUE OF ATTENDANTS.

A MORO DATO AND HIS WIFE, WITH A RETINUE OF ATTENDANTS.

CHAPTER IX

THE MOROS

n reaching Mindanao, the land of the Moros, we went ashore at Camp Overton, where we were met by army officers and dougherties drawn by teams of six mules. After a hand-shake at the commanding officer's home, we were furnished with a big escort of cavalry and started climbing up, up, among the hills. Soldiers were hidden in the tall grass all along the way to make sure that nothing would happen to "the great White Sultan with the big Red Flag," as the Moros called the Secretary. Army men could not go out alone, even in those days, for they were attacked by bands and killed, principally to get their weapons, which the Moros were very keen to possess. The datos, the head men of the Moro tribes, were allowed to have guns, but none of the other natives. A storm came up, however, not long ago on Lake Lanao, at Camp Keithley, and for fear that his boat would upset, General Wood had a great deal of ammunition thrown over[Pg 326]board, which, it was discovered, was subsequently fished up by the natives.

The Moros are Mohammedan Malays. They came in their boats from islands further south, and in 1380 were converted to Islam by an Arab wise man, Makadum,[26] who made his way to Sulu and Mindanao.One hears then of Raja Baginda, who came from Sumatra in 1450; his daughter married Abu Bahr, the law giver, who established the Mohammedan Church and, after his father-in-law's death, became sultan and founded a dynasty. In the old days the Moros were all pirates and slave traders. Both Spanish and American authorities have tried to suppress slavery, but it still exists. It is said a woman will bring about forty pesos.

A dato's slaves to-day are well treated, and form part of the family. A slave, moreover, has a chance to rise in the social scale, for Piang, whom we met, was once a slave, but became a powerful chief and a friend of the Americans.

The ruler of all the Moros is the Sultan of Sulu, whom we did not see because he was in Europe at the time we were in the Islands. It is said that a few years ago he would some[Pg 327]times appear in the market on the back of a slave, with an umbrella held over his head. Here he would stay while the people kissed his hands and feet. He may have changed his customs since his trip.

Dampier, who visited the northern islands of the Philippines, has also left us notes of his stay on Mindanao, which are still true in the main. He says:

"The island of Mindanao is divided into small states, governed by hostile sultans, the governor of Mindanao being the most powerful. The city of Mindanao stood on the banks of the river, about two miles from the sea. It was about a mile in length, and winded with the curve of the river. The houses were built on posts from fourteen to twenty feet high, and in the rainy season looked as if built on a lake, the natives going their different ways in canoes. The houses are of one story, divided into several rooms, and entered by a ladder or stair placed outside. The roofing consists of palm or palmetto leaves.... The floors of the habitations are of wicker-work or bamboo.

"A singular custom, but which facilitated intercourse with the natives and vice versa, was of exchanging names and forming comradeship[Pg 328] with a native, whose house was thenceforth considered the home of the stranger."

Alimund Din's name stands out in this meager Moro history beyond all others, for he was the first and only Christian ruler in this land. Even before he became a Christian he was a reformer, and suppressed piracy. He not only coined money but had both an army and a navy, and lived in such splendour as probably has not existed since those days, among the Moros.

Alimund Din ruled about the middle of the eighteenth century, in the time of Philip V of Spain. In return for ammunition to enable the Spanish to keep down piracy, he allowed the Jesuit fathers to enter his country. In time, however, they caused trouble among the Moros, and civil war broke out, as Bautilan, a relative of Alimund Din's, preferred the Mohammedan religion to the new ideas of the Jesuits. Alimund Din and his followers took flight in boats, and in time reached Manila, where they interceded for Spanish protection. The Spaniards showered him with presents, gave him a royal entrance into the city, and finally converted him to Christianity. Later, he was sent back, escorted by Spanish ships, but Bautilan's fleet attacked them. As the Spaniards suspected Alimund Din of becoming a Christian not [Pg 329] entirely for Christianity's sake, they threw him into prison. The throne was restored to him in 1763 by the English, who occupied this part of the island for a short time.

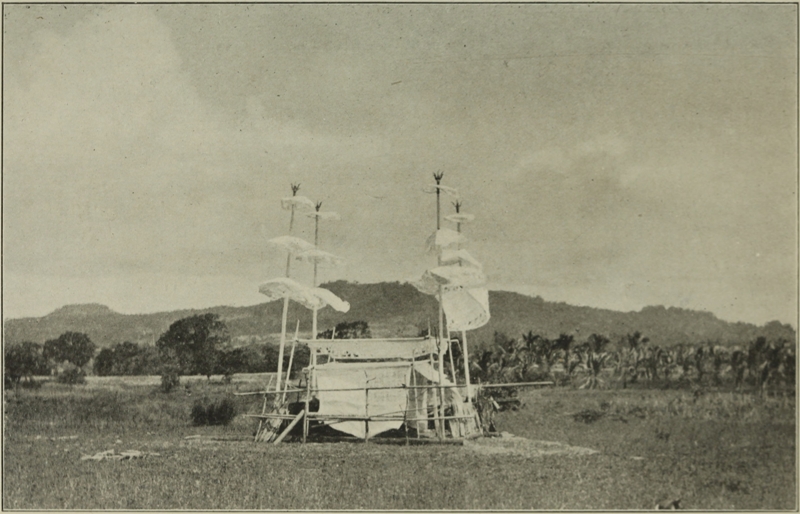

A MORO GRAVE.

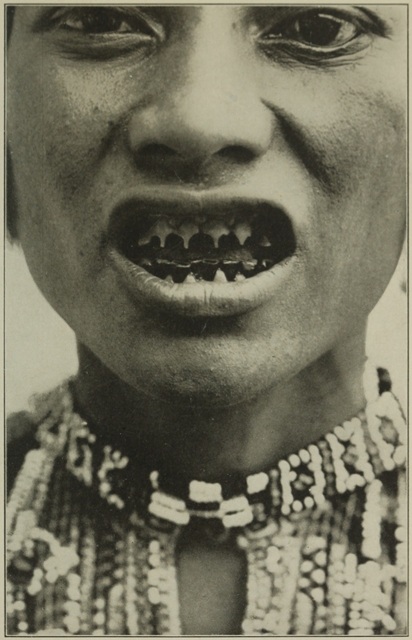

A MORO GRAVE. The Moros are smaller than the East Indian Mohammedans, but are strong and slight, and have fine features. They appear especially cruel and determined because their teeth are black from buyo. In war time, many of the women fought beside the men, and it is supposed to be they who mutilated the Americans found dead on the field after battle. The peo[Pg 330]ple whom we met on the road with their ponies loaded with hemp seldom smiled and did not bow, but they looked us straight in the eye, and there was no touch of sulkiness about them.

It is very difficult to distinguish the men from the women, as they dress much alike. But you see few of the latter on the road, for being Mohammedans, most of them are kept at home. They are not veiled like other Moslem women, except when first married.

The costumes of the Moros differ to such a degree—and for no reason that I could discover—that it is difficult to describe them. Many wear tight trousers, which are something like those of the Spaniards—so tight that they are sewn on the men and never come off until worn out—and are often bright red or yellow in colour. On the other hand, some wear very loose, baggy trousers or skirts of different shades. Indeed, they are the most gaily dressed people I have ever seen, and their brown skins set off the vivid yellows and greens and reds and magentas and purples of which their trousers and jackets and turbans and handkerchiefs are made. The jackets have a Chinese appearance. The turbans might be old Aunt Dinah's of the South. The sashes, which are woven in the Moro houses, are of silk, bright[Pg 331] green and dark red being the predominant colours. They are knotted on one side, generally a kriss or a bolo being held in the knot, and are tied about the waist so tightly that the men look almost laced, and perhaps that accounts for their womanish appearance.

When the American army first occupied this region they treated the Moros well and found them friendly. Take for instance Zamboanga in the south, an especially interesting region. When the American soldiers entered, the Spanish guard left the garrison, and the Spanish population and the priests followed. The Americans found outside the town gates a large barbed wire bird cage, where the Moros had been compelled to leave their arms before entering the town at night, to avoid an uprising. The government of Zamboanga at this time was reorganized by the American officers. A Filipino presidente was appointed, a dato to head the Moros, and a Captain Chinese, as he was called, to manage his people, who were mostly merchants and pearl fishers.

Mindanao was under a military-civil government that worked wonders, for in a few years many of the Moros were brought under control, and they became loyal Americans, although they had always been bitter enemies of the Filipinos[Pg 332] and the Spaniards. They say they have found the Americans brave, and have not been lied to by them, and so they seek our protection. Although the Moro and the head-hunter are so different, they are alike in one respect—if they care for an official and have confidence in him they do not want him changed. It is the man they are willing to obey rather than the government. Of course, there are thousands of them, fierce as ever, back in the mountains, and they are still fanatic and wild. Even among those who are under control, the greatest care has to be exercised, for they have the hatred of the Christian deep in their hearts, and they may run amuck at any moment and kill till they are killed; but this is a part of their faith, they ask no quarter, and nothing stops them but death.

Besides the danger of their attack by religious mania they have a great desire for rifles, as I have said, and they are always "jumping" the constabulary, attacking small parties suddenly from ambush and cutting them down with their knives, or killing sentries; so that constant care has to be used, and the sentinels walk at night in twos, almost back to back, so as to have eyes on all sides. A few weeks before we arrived there had been several cases of "jumping."[Pg 333]

An American army officer told me the fights with the Moros generally occurred on the trails among the hills; as the foliage is so thick, it is easy for the natives to conceal themselves on either side, sometimes in ditches, and give the Americans a surprise. For this reason, a drill was found necessary for single file fighting. Every other soldier was taught to respond to the order of one and two. When an attack was made, the "ones" shot to the right, the "twos" to the left. This proved successful. The same officer said the Moros would often use decoys to lead the troops astray. Seeing fresh tracks, they would hasten on in pursuit, and be led away from their supplies, while their enemy would be left behind to attack them in the rear. Walking on the mountain trails was very hard on the soldiers' shoes, and on one of these expeditions their boots gave out, so they were obliged to make soles for their shoes out of boxes and tie them on with leather straps.

Up, up we drove; the clatter of the cavalry could be heard in front and behind, and the dougherty, how it did rattle! It was a pretty sight to see the party traveling through the tropical forests and winding across the green uplands, with their pennons and the Secretary's[Pg 334] red flag (which made a great impression on the natives, we heard), and the wagons rumbling along, with a rearguard behind and the scouts in the distance. John, the coloured man, snapped his whip, and the mules trotted along, and the air became cooler, and we drove over a plain where real mountain rice was planted. Occasionally a Moro shack could be seen in the distance.

At an outpost, where we stopped to change mules, we saw a beautiful waterfall, perhaps the loveliest that I had ever seen, called Santa Maria Cristina. From a greater height than Niagara it plunged down into a deep valley of giant trees. It reminded me of a superb waterfall near Seattle.

At last we reached Camp Keithley, on the mountain plain, a forlorn lot of unpainted houses with tin roofs and piazzas, but beautifully situated, like some station in the Himalayas. There was splendid mountain scenery disappearing into the distances, and views of the ocean far away, and, on the other side, the great lake of Lanao, an inland sea more than two thousand feet above the ocean, with imposing ranges about. This lake, which has always been the center of Moro life, is surrounded by native villages, and the military post is impor[Pg 335]tant and much liked by the officers quartered there.

The Secretary, my husband and I were billeted on Major Beacom, the commanding officer—Mrs. Dickinson had not felt quite equal to the trip. The Major's house was very attractive, and his little German housekeeper gave us excellent food and made the orderlies fly about for our comfort.

We went almost at once to the market place, which was intensely interesting. The gorgeous colours and gold buttons of the costumes were magnificent. Brass bowls for chow were for sale, and betel-nut boxes inlaid with silver, and round silver ones with instruments attached to clean the ears and nose. There are four compartments in these betel-nut boxes—for lime, tobacco, the betel nut, and a leaf in which to wrap the mixture called buyo.

Here we saw the spear and shield dance. The dancer had a headdress that covered his forehead and ears, making him look quite ridiculous, absolutely as though he were on the comic opera stage. With shield and spear he danced as swiftly and silently as a cat, creeping and springing until your blood ran cold, especially as you knew he had killed many a man.[Pg 336]

In the afternoon, after reviewing the troops and inspecting the quarters, we crossed a corner of the lake and landed at a Moro village. It was raining hard and the mud was deep. We waded through a street, followed by the people in their best clothes—one in a black velvet suit, another in a violet velvet jacket. I saw only two women in the streets; they were not veiled nor brilliantly dressed, but had red painted lips and henna on their nails. The Moro constabulary here wore red fezzes and khaki, and the officer in command at the time was of German birth.

A MORO DATO'S HOUSE.

A MORO DATO'S HOUSE. Into one of these houses we were invited. We mounted the ladder to the one large room in the front, into which the sliding panel shutters admitted the air freely, so that it was cool and shaded. Here sat the wives and the slaves in a corner, playing on a long wooden instrument with brass pans, which they struck, producing high and low sounds, with a little more tune than the Igorots. The big room was bare, except for a long shelf on which was some woven cloth and a fine collection of the native brass work, for this is the center of the brass-workers.

We moved on through the little town of nipa houses to visit old Dato Manilibang, whose house was not as fine as those we had seen before, but where we were admitted into two rooms. From the entrance we streaked muddy feet across the bamboo-slatted floor into his reception room, where a sort of divan occupied one side—on which the Secretary was asked to sit. Behind this cushioned seat were piled the boxes with the chief's possessions, and here he sits in state in the daytime and sleeps at night. The women, who were huddled together on one[Pg 338] side of the room, wore bracelets and rings, and one was rather pretty.

At dawn we were up and off again. What a day! We had two hours on a boat crossing a lovely lake, surrounded by mountains, on the shore of which some of the wildest Moros live. Our boat was a big launch, a sort of gunboat, which, strangely enough, the Spaniards had brought up here and sunk in the lake when the war came on, we were told, and which had been resurrected successfully. It was a steep climb up the opposite side of the lake, but most of us scrambled up on horses, till we topped the ridge and came to Camp Vickers, a station with fine air and outlook but rather small and pathetic.

The picturesque Moros had gathered here to greet the Secretary, and their wail of welcome was something strange and weird. A dato would come swinging by, followed in single file by his betel-box carrier, chow bearer and slaves. Some of the chiefs rode scraggly ponies, on high saddles, with their big toes in stirrups of cord almost up under their chins, and with bells on the harness that rattled gaily. And, of course, the tom-toms kept up their endless music.

We had two more hours of horseback riding—we hoped to see a boar hunt, but owing to [Pg 339] some misunderstanding, it did not come off. Then, after a stand-up luncheon at Major Brown's, we started down the trail again in a dougherty.

BAGOBO MAN WITH POINTED TEETH.

BAGOBO MAN WITH POINTED TEETH. The tree-dwellers just referred to are the Manobos and the Bagobos with pointed teeth—for Mindanao is not entirely inhabited by Moros; there are supposed to be no less than twenty-four tribes on this island alone. They build in trees, to escape the spear thrusts of their neighbours through the bamboo floors. We were to make their acquaintance later.[Pg 340]

A drenching rain came on that afternoon, through which the escort jogged along, while we clung in our dougherties, nearly shaken to pieces, and reached Malabang, on the other side of the island, as much fatigued as if we had been on horseback all the way. The military post here was most attractive, with the prettiest of nipa houses for the officers, and the parade lined with shading palms, and flower-bordered walks—a charming station. We were quartered with Lieutenant Barry and his wife, a delightful young couple, in their thatched house, and dined with Major Sargent, the commanding officer, who has written some good books on military topics.

The Celebes Sea was calm and lovely when we left Malabang. We passed along the coast of Mindanao toward a long lowland that lay between the high mountains of the island. This was the plain of the Cotobato, a great river which overflows its banks annually like the Nile and has formed a fertile valley that could be turned to good account. The mouth of the river is shallow, so that we were transferred to a stern-wheel boat that was waiting, and began to work our way up, against the rapid current, past low, uninteresting banks that were proving[Pg 341] rather monotonous, when suddenly we turned a point and saw the town of Cotobato.

The Moros and the other tribes were in their full splendour here. Soon, down this tropical river, where crocodiles dozed and monkeys chattered and paroquets shrieked, there came a flotilla from the Arabian Nights, manned by galley slaves. On the masts and poles of one of the barges floated banners, and under the canopy of green sat a real Princess. Some of the boats were only dugouts with outriggers, but they were decorated, too, and all the tribes were dressed in silks and velvets of the brightest colours.

There was great excitement and much cheering as we approached the landing stage, and the troops stood at attention, while the rest of the shore was alive with the throng of natives in all the colours of the rainbow. The Secretary inspected the troops, and we saw for the first time the Moro constabulary, wearing turbans and sashes, but with bare legs; nevertheless, they looked very dashing. Indeed, the Moros were so different in character and appearance from any people we had seen before that they might as well have come down from the stars.