[Pg 121]

THE PHILIPPINES

[Pg 122][Pg 123]

THE PHILIPPINES

CHAPTER I

MANILA AS WE FOUND IT

igh on the bridge of the Pacific Mail Steamer Siberia we stood as we passed through the Boca Chica—the narrow channel—into the historic waters of Manila Bay. On one side was the mountainous island of Corregidor, rising steeply out of the sea and masking in its tropic growth many batteries and guns, on the other was the splendid mountain, Mariveles, and in the distance fine ranges rising from the sparkling ocean. Far away on the horizon, across the huge bay, lay Manila, the capital of the Philippine Islands.

Three weeks before we had left Hawaii, two days later we had steamed by Midway Island. Then we passed a few days in Japan, and coasted along the superb island of Formosa, rightly named "the beautiful"—where great mountains dipped down into the still sea—and now we were entering the Philippines, the real objective point of the official party—there were eight of us—in which we were so fortunate as to[Pg 124] be included. We were at last going to see the interesting results of Spanish rule for three centuries, upon which were being grafted all the energy and scientific and social knowledge of the twentieth-century American.Although both Hawaii and the Philippines are under American rule, they are like different worlds. The Land of the Palm and Pine is a much bigger problem for the United States than Hawaii. The latter is nearer home, a smaller group of islands, and is quite Americanized. It is the commercial hub of the Pacific, an important coaling station, an outlying protection for the California coast. The natives are of Polynesian extraction and American education; they are quite unlike the Filipinos in character, who are Malaysian and have had centuries of Spanish influence. The Filipinos clamour for independence, the Moros and the wild tribes must be carefully handled, while the Hawaiian is contented with his lot. Besides the necessity of maintaining an army in the Philippines so far from home, one hundred and one other difficulties are to be considered. With these facts in mind, we looked forward to interesting experiences in the Islands, and we were not disappointed.

As we approached Manila, some small scout [Pg 125] boats, all flag bedecked, came out and joined us, and fell in behind in procession, then larger boats, one bringing the excellent Constabulary Band, which played gaily. Another, which had officials on board, exchanged greetings with us across the water, and others with unofficial people added their welcome. Quarantine was made easy, and all difficulties with customs officials were spared us. When we reached the dock it was massed with the people who had landed from the boats and with crowds from the town.

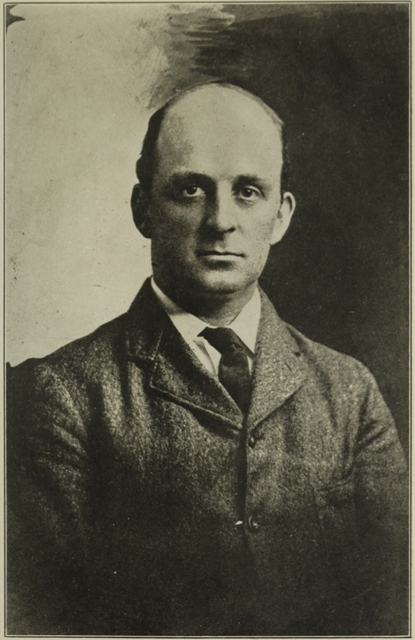

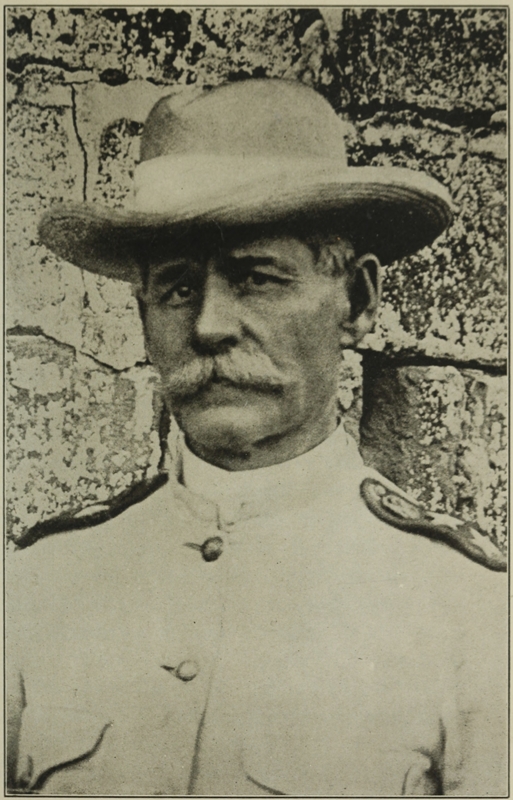

GOVERNOR GENERAL CAMERON FORBES.

GOVERNOR GENERAL CAMERON FORBES. After the reception on shipboard the Secretary and Mrs. Dickinson and the official members of the party were whirled off in autos, with a squadron of cavalry clattering along as escort. Another motor was waiting for us, and we soon joined the procession as it moved to the palace.

We were much interested in the sights in the[Pg 126] streets. There were numbers of carromatos, little covered two-wheeled carriages, drawn by stocky Filipino ponies. The streets in this part of the town are wide, and the houses have overhanging balconies, in Spanish style. In honour of the Secretary, the buildings were draped with flags. Near the wharf the land had lately been filled in, and great docks were in construction. There was a new boulevard near the old Luneta, and an avenue named after President Taft, besides a big hotel and a hospital that had then just been finished. The harbour was filled with vessels, electric cars were running, and autos were to be seen, so at first it all looked quite up to date, until you met a carabao slowly swaying down the street, hitched to a two-wheeled cart, with a brown boy in red trousers, piña shirt and a big straw hat sitting on his back—"carry boy," as Secretary Dickinson named the animal. The "carry boys" do not like white people, and sometimes charge them, stamping and goring them with their horns, but a small Filipino boy seems to have perfect control of them, and if they are allowed occasionally to wade in a puddle, which cools them off, they do not "go loco," or crazy.

It was in the palace of Malacañan, or Government House, as it is sometimes called, that Sec[Pg 127]retary and Mrs. Dickinson and ourselves stayed with the Governor General. This is a large, rambling structure in a garden by the Pasig River. Under the porte-cochère we entered a stone hall, off which were offices, then went up a long flight of stairs to a big hall looking into a court. This hall was hung with oil paintings of Spanish governors, quite well done by native artists, and in the center stood a huge one-piece table of superb nara wood, covered with gleaming head-axes and spears, bolos, krisses, campilans, and lantankas, used by the wild tribes and Moros.

Our rooms were large and empty, as was the entire palace—indeed, so are all the houses on account of the heat. The polished floors, too, are made of huge planks, sometimes of such valuable tropical woods as rosewood and mahogany, and are left bare. It took a little time to accustom ourselves to the hard beds with rattan bottoms, covered only by two sheets. They were carved and four-posted, and draped with mosquito netting. Two little brown lizards squeaked at us in a friendly manner, and crept down the walls, out of curiosity, no doubt, little ants kept busily crawling across the room in a line, and the mosquitoes that hid in my clothes in the rack during the daytime buzzed about at[Pg 128] night. The heat was great, notwithstanding the electric fan, but the sliding screens that formed the sides of the room gave us some relief. These shutters are like Japanese shoji, made of small panes of an opalescent shell to soften the intensity of tropic sunlight, with green slit bamboo shades pulled halfway down.

When I used to write or read I sat on my rattan bed under the mosquito netting; there I could look out of the parted sides of the house to the red hibiscus border of the garden stretching along the narrow Pasig. Boatmen, in conical straw hats, perched at the ends of their bancas, paddled the hollowed-out logs rapidly through the water, or floated idly by, smoking their cigarettes; these boats were loaded to the gunwale with green grasses, and had canopies of matted straw. Launches, too, came chugging past, towing the big high poops covered with straw-screened cascos. Over beyond the river was a flat all in a green tangle, with the thatched nipa houses on their stilts. For the palace stands outside the more thickly settled parts of the city, which in turn surround the walled town.

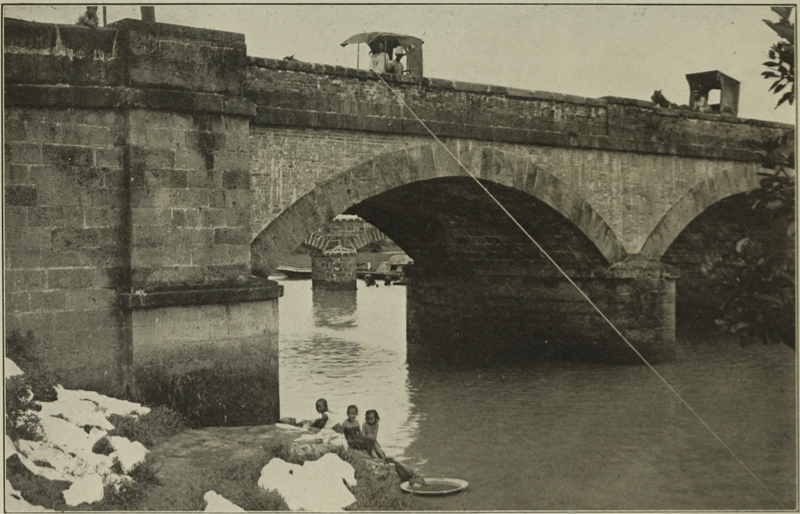

The Pasig River

Manila to-day is a curious mixture of native nipa shacks and old Spanish churches and forts with the up-to-date American buildings and [Pg 129] improvements. There are the different quarters, as in all cities of the Orient—Chinese, native and so on—and each has its own distinctive sights. The street smells, which are never lacking in a city, reminded us of India.

The walled city has picturesque gates breaking through the old gray battlements—the massive wall was begun in 1590—and ancient sentry houses at the corners, while behind rise the white balconies of old convents and monasteries, and buildings now used for government purposes, and towers of churches. The old moats have been filled up for sanitary reasons and are being made into wide sweeps of lawn and flower gardens, and the famous Malecon, the drive beneath the city walls, which was once upon the sea front, has been removed too far inland by the filling of the harbour to retain its old charm.

"Intramuros" (within the walls) more than half the land belongs to the Church, and church buildings abound. These are really inferior, compared with those we saw in Mexico, but some of them are very old. The Augustinian Church, finished in 1605, has enormously thick walls and a stone crypt of marvelous strength.

In the center of the town is Plaza McKinley, but the main business street is the narrow[Pg 130] Escolta, made to look still narrower by the overhanging second stories of the buildings.

We visited the botanical gardens, a shaded park with winding paths beneath acacias and mango trees. We drove, too, through the narrow streets of the suburb of San Miguel, where we looked into tangled gardens of tropical plants, behind which were houses with broad verandas and wide-opening sides, covered by a wonderful screen of a sort of mauve morning glory, which blooms, however, all day long.

The native houses are built of bamboo with braided grass walls and thatched roofs, and are raised on stilts because of the rainy season. We went to order some embroidery one day of a Tagalog woman. Climbing a ladder into a small house, we saw the whole family sitting on the floor, working over a long frame. In some of these shacks they have a small room for visitors, with chairs and a table, and cheap prints of the Virgin on the walls. Under the house are kept usually a pig and a pony. One woman was very successful—she not only had waist patterns to show and to sell, but had a standing order from Marshall Field, in Chicago. We also visited a still more prosperous embroidery house, built of stucco, with a courtyard. These people were Spanish mestizos.[Pg 131]

A visit to the cigarette factory to which we were taken by Mr. Legarda showed us one of the characteristic industries of the city and gave us an idea of the deftness and quickness of those who are employed in this work. The little women who pack the cigarettes can pick up a number of them and tell in a twinkle by the feeling just how many they hold, and the cigar wrappers work with greatest rapidity and sureness and make a perfect product. It was all very clean and fresh, with hundreds of employees in the large, airy rooms. A band played as we went through the building, and we had a generous luncheon and received innumerable presents from the managers.

Opportunity was given us for sundry little exploring trips into the suburbs of Manila.[11] We rode on horseback, in company with Secretary Dickinson, Governor Forbes and General Edwards, among little native shacks, through overgrown lanes beyond the city, and along the beach, where we saw fishermen's huts and men mending their nets, to the Polo Club. The[Pg 132] Governor, who was most generous in giving money of his own to benefit the Islands, not only built the clubhouse and laid out the field at his own expense, but even imported Arabian horses and good Western ponies. This club is a fine thing to keep army officers in good condition and give them exercise and amusement, as well as to bring good horses into the Islands. The clubhouse, of plaited grasses, bamboo and wood, is on the edge of the beach, from which one can see the beautiful sunsets across the bay and catch the faint line of the mountains in the distance. It all seemed very far-away and tropical and enchanting.

The English-speaking residents of Manila have various other clubs, among which the Army and Navy, the English, and the University are perhaps the most important. The Officers' Club, at Fort McKinley (seven miles from Manila) has a superb situation, commanding a fine view of the mountains.

As we landed in Manila early Sunday morning, we were in time for service in the Episcopal cathedral, which had just been built. This is a handsome building in the Spanish style, large and airy, with an effective altar. It was erected by an American friend of Bishop Brent, the Episcopal bishop, who has done fine work in the[Pg 133] Islands. According to a story that is related of this good man, he made a journey at one time into the interior of Luzon, where he found the natives sadly in need of instruction in ways of personal cleanliness. As soon as he reached the mail service again, he wrote to America for a ton of soap, which was duly shipped to him and used for the purification of the aborigines.

I was glad to visit also Bishop Brent's orphan school, consisting principally of American-mestizo children. The native women, when deserted by their white lovers, generally marry natives, who often ill-treat these half-white children, and sometimes sell them as slaves. Miss Sibley, of Detroit, was in charge of this school, which was in a big, comfortable house near the native shacks on the edge of the town, and had twelve pupils at that time.

A convent of Spanish nuns on a small island in the river, interested me greatly. It was then under the supervision of the government, for it was at that time not only a convent but also a poorhouse, a school for orphans, an asylum for insane men and women, and a reformatory for bad boys. The embroidery done at the convent was better than that made by the natives in their houses, as the thread used was finer. The nuns charged more than the natives, but they[Pg 134] would also cut and sew, thus finishing the garments. Articles embroidered by native women were never made up by them, but had to be taken to a Chinese tailor.

The linen must first be bought, however, so I tried to do a little shopping in the city, but found it very unsatisfactory. The shops are poor, and, as one traveler has said, you can get nothing you want in them, but plenty of things you don't want, for which you can pay a very high price.

One day I was taken to a cockpit, where a cockfight was to come off. This is one of the characteristic amusements of the Filipinos, which they have engaged in since the year 1500. It is so popular that it would be difficult to put a stop to it all at once, but it has been restricted by the government to Sundays and legal holidays, which is something of a victory. (They are also passionately fond of horse racing, in regard to which other restrictions have been made.) Outside, beggars, old and blind, were crawling over the ground; natives strolled around, petting their birds, which they carried under their arms; and vendors with dirty trays of sweetmeats wandered about. We bought our tickets and passed into the rickety amphitheater.[Pg 135]

Cocks were crowing, and such a howling as went on, the audience all looking toward us as we entered. It seemed as if they were angry with us for stepping into the arena, and yet there was no other way to reach the seats. Our guides pointed to a shaky ladder that led into a gallery, but we preferred to sit far back in the chairs about the pit. There were natives, Chinese, and mestizos present. We soon discovered that they were not angry with us, but we had entered at a moment when the betting was going on, and the cocks in the ring were so popular that there was great excitement.

Each cock was allowed to peck the neck of the other and get a taste of blood, while they were still held under their owners' arms. The fighting cocks did not look quite like ours. They were armed for the fray with sharp "slashers" attached to their spurs. When the betting had subsided the cocks were left to themselves in the ring, and they generally went for each other at once. What a hopping and scuttling! Feathers flew, the crowd cheered, and the cocks went at each other again and again until they were hurt or killed. The referee then decided upon the victor. Sometimes the cocks did not seem to interest the crowd, and then their owners would take them out of the[Pg 136] ring before fighting; at times the cocks refused to fight. It was not so exciting as I had expected, and when we considered that the birds were to be eaten anyway, it did not seem so cruel and terrible as I thought it would.

Speaking of cocks being eaten, the principal foods of the Filipinos are fowls and eggs, as well as rice, fish and carabao meat, but as the "carry-boys" are good workers they are not often eaten. Pigs are kept by the Filipinos, and are put on a raised platform for about six weeks before killing, so as to keep them clean and fatten them with good food. Salads, crawfish and trout, as well as cocoanut milk, red wine and wild coffee, are among the things they live on. Army people in the Islands often have, in addition, wild deer and wild boar which are shot by the American officers, besides excellent game birds, such as the minor bustard, jungle fowl, wild chicken, quail, snipe and duck.

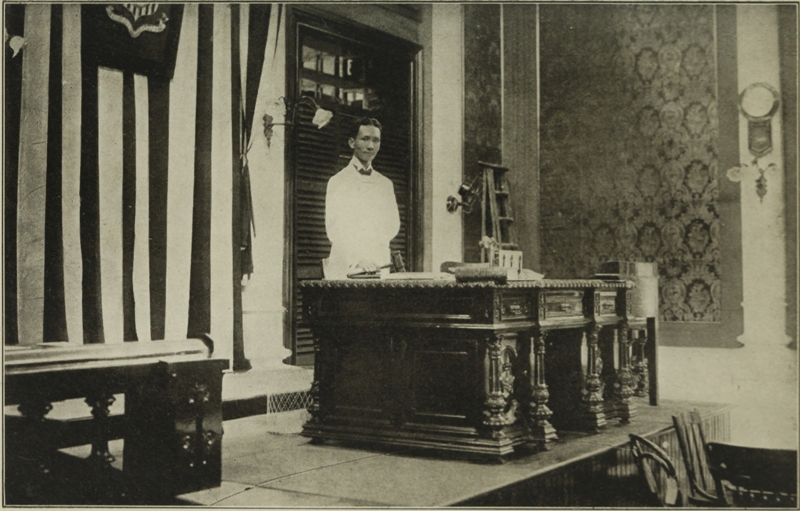

MALACAÑAN PALACE.

MALACAÑAN PALACE. After most of the guests had arrived, there was a rigodon of honour, in which all took part. The rigodon is the dance of the Filipinos, and of so much importance to them that it was considered essential that the Secretary and his party should be able to join in it. Accordingly, we had all practised it on the ship before reaching Manila. It is said that ex-President Taft won much of his way into the hearts of these island people by his skill and evident delight in this dance, which is something like a graceful and dignified quadrille, with much movement and turning.

To show that traveling in an official party is not "all play and no work," I may just note the program carried out by the men on the day fol[Pg 138]lowing this reception. Rising at six o'clock and taking an early breakfast, they went on board the commanding general's yacht and cruised across Manila Bay to visit the new defenses on the island of Corregidor, which rises a sheer five hundred feet out of the water. For hours they moved from one place to another in the heat, inspecting huge guns and mortars and barracks and storehouses, all hidden away so as not to be seen from the sea, although great gashes in the cliffs showed where the trolley roads and the inclined planes ran. It is really the key to our possessions in the Far East. Thousands of men were working like ants all over the place. It was two o'clock before the party reached the tip-top, where they had a stand-up luncheon at the quarters of the commanding officer. Then they came back to the yacht, and fairly tumbled down just wherever they happened to be for a siesta. They were then taken to Cavite, ten miles away, which is one of the two naval stations. There they landed again and visited the picturesque old Spanish fortifications and the quarters.

A baile, or ball, was given in honour of the Secretary by the Philippine Assembly, at their official building, where all the ladies of our party wore the Filipina dress. This is ordinarily [Pg 139] made of piña cloth, a cheap, gauzy material, manufactured from pineapple fiber. The waist, called camisa, is made with winglike sleeves and a stiff kerchief-like collar, named panuela. The skirt may be of any material, quite often a handsome brocade, and among the Tagalogs a black silk open-work apron finishes the costume. The white suits and uniforms of the men and the bright-coloured dresses made this ball a gay and lively scene. The band played incessantly, and after the Secretary and Mrs. Dickinson had stopped receiving at the head of the stairs, there was a rigodon, which we all danced in as stately a manner as we could. But my most vivid recollection of the ball is of the heat and the pink lemonade, which poisoned a hundred people and made me deadly ill all that night.

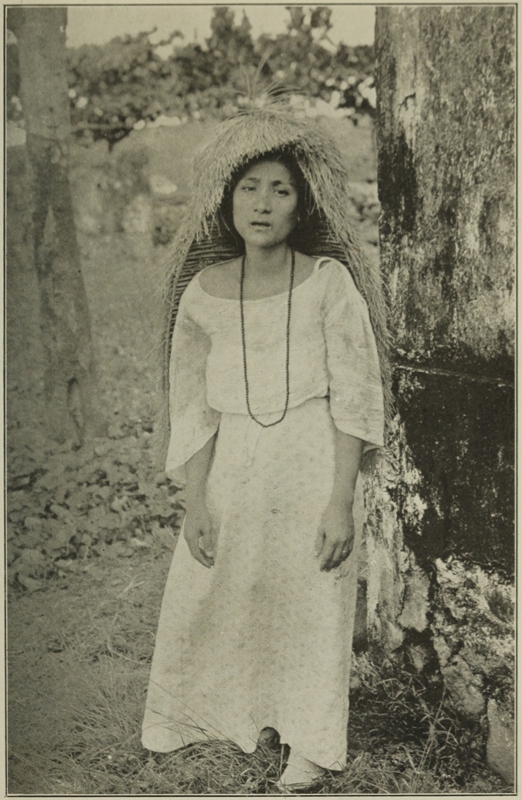

MRS. ANDERSON IN FILIPINA COSTUME.

MRS. ANDERSON IN FILIPINA COSTUME. The Government Dormitory for Girls, which we visited, I found most interesting. There were one hundred and fifty, eight sleeping in each room. These girls came from different provinces all over the Islands. As there are so many distinct dialects, some of them could understand one another only in English, and no other language is allowed to be spoken. One of the girls made a speech in English welcoming the Secretary and did it extremely well. Having learned, among other things, to cook, they gave us delicious tea and cakes and candies on a half-open veranda among the vines and Japanese lanterns. Some were taking the nurses' course, which seemed to be the most popular. These pretty girls danced for us in their stiff, bright-coloured costumes, swaying and waving their hands, and turning and twirling in their languid but dignified manner. It appeared to be a mixture of a Spanish and a[Pg 141] native dance, and was altogether quite charming.

A morning with Mr. Worcester at the Bureau of Science was most delightful. This bureau is so much more than a museum of scientific specimens that I cannot begin to do justice to it in a single paragraph. It was started at first as a Bureau of Government Laboratories in charge of the chemical and biological work of the government, the departments of zoölogical and botanical research were subsequently added, and finally the Bureau of Ethnology and the Bureau of Mines were incorporated with it. Not only were all these departments coördinated under one head, preventing overlapping and securing economy and efficiency of administration, but this work was correlated with that of the Philippine General Hospital and the College of Medicine and Surgery. When this comprehensive plan was formed all the scientific work of the government was carried on in "a hot little shack," and the scheme was commonly referred to as "Worcester's Dream," but at the time of our visit the dream had come true. The departments were manned by thoroughly trained men from the States, and the Bureau of Science was one of the world's greatest scientific institutions.[Pg 142]

The Philippine Bureau of Science "is now dead." When the Democratic Administration took charge it was announced that all theoretical departments, such as ethnology, botany, ornithology, photography and entomology (!) were to be "reduced or eliminated." It was afterward made plain that all work which was considered practical would be continued, but the mischief had been done, the men who made the institution had left, and under present conditions it is impossible to secure others who are equally competent in their place. Our only consolation is to be derived, as Mr. Worcester himself says, "from contemplating the fact that pendulums swing."

Though so recently established, the museum contained in 1910 a wonderful exhibit of the plants and animals of the Islands. We took a peep into the butterfly room, where we admired some rare and lovely ones with a feathery velvet sheen the colour of the sea. We saw also the huge brown Atlas moth touched with coral, like a cashmere shawl, with eyes of mother-of-pearl on his wings. We noticed that the females were larger than the males, and even those of the same variety often differed greatly in colour. In one case a female was big, and[Pg 143] brown and violet in colour, while her mate was small, and blue and yellow.

In the next room were beetles, some of which were like the matrix of turquoise, and others had shimmering, changeable shades of green and bronze. There were beetles like small turtles, and long, horned beetles like miniature carabaos.

Afterward we visited the birds. Bright-coloured sun birds, with long beaks, which feed on the honey of flowers; clever tailor birds, small and brown, with green heads and gray breasts, which sew leaves together with vegetable fiber to make their nests; birds of whose nests the Chinese make their famous soup, and the blue kingfishers, of whose brilliant feathers these same Chinese make jewelry; fire-breasted birds, too, and five-coloured birds. There were birds that build their nest four feet or more under the ground, and hornbills, that wall up their wives in holes in the trees while they are hatching their eggs, the males bringing them food and dropping it through a small opening. There, too, I saw the fairy bluebird.

Near by, we visited an orchid garden, and passed under gates and bamboo trellises dripping with every kind of orchid. The Philip[Pg 144]pines are the paradise of these remarkable plants, and many are the adventures that collectors of them have had in the interior of these Islands.

Then we passed into the Jesuit chapel and museum. We were greeted at the door by several black-robed priests, who smiled and bowed and talked all at once. They escorted us first to the museum, where there were cases of shells—heart-shaped shells, trumpet shells, scalloped shells big enough for a bathtub—all kinds of shells, and the paper nautilus, which is not a shell but an egg case. Then there were land shells, polished red and green, Venus' flower baskets, exquisite glass sponges, corals of all kinds—fine branches of the red and the white—and an enormous turtle that weighed fifteen hundred pounds.

In the cases at the side of the room were animals of the country—flying monkeys, with sucking pads on their toes to help them climb the trees, big, furry bats and flying lizards. A tiny buffalo, which was discovered only a few years ago up in the hills, and a small spotted deer were in the collection. A big monkey-catching eagle, white and brown, was here, and the paroquet that carries leaves for her nest in her red tail, as well as a pigeon with ruffs of green and[Pg 145] blue about her neck, and a bald crown, which was caused, the natives say, by flying so high that her head hit the sky.

Numerous entertainments and receptions were crowded into that too short visit to Manila. July 25th had been declared a national holiday. A musical program was given in honour of the Secretary by five thousand Manila school children. One afternoon Mrs. Dickinson received some of the Filipina ladies, who sang and played on the piano quite well.

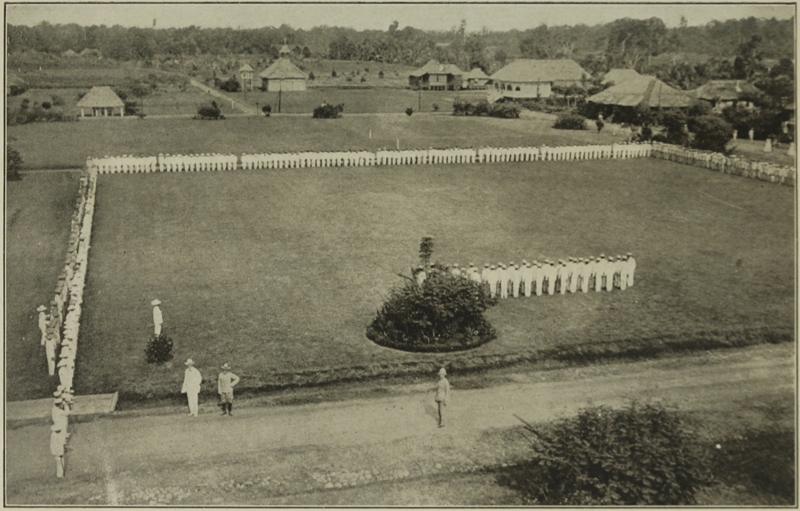

Another day the officers and ladies at Fort McKinley entertained the party at luncheon at the Officers' Club. Before luncheon there was a military review in which the troops from all over the islands participated, followed by some good shell firing out in the chaparral, as under war conditions, and a display of wireless work. A special drill was given by Captain Tom Anderson—the son of General Anderson—whose company was one of the best drilled in the army, and went through the manual and marching with only one order given, counting to themselves in silence the whole seventeen hundred counts, all in perfect unison.[12]

[Pg 146]

In the Secretary of War's speech that afternoon he took occasion to say, "General Duvall, you have not said too much in favour of the Army. You have not overdrawn the picture, for a steadier moving column or brighter eyed men and a more soldierly set of men I have never seen anywhere."

The reception by General and Mrs. Duvall was a brilliant affair, chiefly of the army and navy. The handsome house with its wide verandas stood in a garden overlooking Manila Bay.

On the Luneta there was, one evening, the largest gathering that had assembled on that historic plaza since the days of the "Empire," for the Secretary of War was expected to be there. The people hoped that he brought with him a proclamation of immediate independence to be announced at that time. The Luneta had once been at the edge of the water, but a great space had been filled in beyond it, and buildings were going up—a large hotel, which would make all the difference in the world to tourist travel in the Philippines, and a huge Army and Navy Club—so that it was planned to remove the Luneta farther out some day, again to the water's edge. On this particular evening, the oval park was crowded with picturesque people,[Pg 147] almost all the men in white, the soldiers in their trig khaki, and the women in their gaily coloured dresses and panuelas. Rows of carriages circled round and round, as the two bands played alternately. After a time we left our automobiles and walked in the throng. A magnificent sunset was followed by the gorgeous tints of the afterglow, and dusk came on and evening fell while we watched and were watched. Soon a thousand electric lights, that were carried in rows around the plaza and over the kiosks of the bands, sparkled out in the darkness. The beauty of the scene, the animation of the crowd, driving or walking in groups, and the refreshing coolness after the heat of the day, made this a lasting memory.

[Pg 148]

CHAPTER II

THE PHILIPPINES OF THE PAST

ow have the Philippines come to present such a unique combination of Spanish and Malay civilization? Let us look into their past. We find for the early days myths and legends, preserved by oral tradition. Two quaint stories told by the primitive mountain people, which show how they believe the Islands first came into being and how the first man and woman entered into this world, are worth transcribing for their naïve simplicity:

"A long time ago there was no land. There were only the sea and the sky. A bird was flying in the sky. It grew tired flying. It wanted something to rest upon. The bird was very cunning. It set the sea and sky to quarreling. The sea threw water up at the sky. The sky turned very dark and angry. Then the angry sky showered down upon the sea all the Islands. That is how the Islands came."This second tale is even more child-like:

"A great bamboo grew on one of the Islands.[Pg 149] It was very large around, larger than any of the others. The bird lit on the ground and began to peck the bamboo. A voice inside said, 'Peck harder, peck harder.' The bird was frightened at first, but it wanted to know what was inside. So it pecked and pecked. Still the voice said, 'Peck harder, peck harder.' At last a great crack split the bamboo from the bottom to the top. Out stepped a man and a woman. The bird was so frightened that it flew away. The man bowed very low to the woman, for they had lived in different joints of the bamboo and had never seen each other before. They were the first man and woman in the world."

These natives believe there are good and evil spirits, and they invoke the agency of the latter to explain the mystery of death. They say the first death occurred when the evil spirit lightning became angry with man and hurled a dangerous bolt to earth.

The first suggestion of real history is found in the traditions that tell of Malays from the south who came and settled on these islands. It is said a race of small black people were already here—the Negritos—who resembled the African negroes, and who retired into the hills before the invaders.

Next we hear of a Mohammedan priest who[Pg 150] came to the southern Philippines and gave the people his religion. His followers have to this day been called Moros.

It was more than two centuries before Captain Cook visited Hawaii, that white men discovered the Philippines. Magellan, the famous Portuguese navigator, while sailing in the service of Spain, landed on Mindanao and Cebu, and took possession of the group in the name of the Spanish king. Before starting from Seville on this voyage around the world, Magellan had already spent seven years in India and sailed as far as Sumatra, so he already knew this part of the world. This time he was in search of the Spice Islands and of a passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. He had touched first at Teneriffe and then crossed the Atlantic to Brazil, making his way along the coast of South America. There were many hardships and difficulties to contend with, and mutiny in the fleet resulted in several deaths. But, as we all know, he persevered, and on the 15th of October, 1520, discovered the straits which were named after him.

The Ladrones were reached after fourteen tedious weeks, and on St. Lazarus' day, in 1521, the Philippines were sighted and named by him for the saint. In the early times they were[Pg 151] sometimes referred to by the Spaniards as the Eastern, and later as the Western, Islands. They were finally named the Philippines by Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, after his king, Philip the Second.

Magellan was quite unlike Captain Cook, whose visit to Hawaii has been mentioned. He was a nobleman and full of the religious enthusiasm that fired the Spaniards of his day. He was accompanied by several friars, who at once began missionary work among the natives, and only a week after his arrival the Cebuan chief and his warriors were baptized into the Christian faith. Unfortunately, Magellan took sides with the Cebuans in their warfare against a neighbouring tribe, and in the battle he was killed. After his death, the same chieftain turned on Magellan's followers, but some escaped to their ships. Out of two hundred and fifty men who had set sail three years before, only eighteen, after suffering incredible hardships on the long journey by way of India and the Cape of Good Hope, returned safely to Spain.

The next explorer who touched at the Islands was the Englishman, Sir Francis Drake, of Spanish Armada fame, who sailed in 1570 on a voyage round the world. We also hear of an[Pg 152]other Briton, William Dampier, a noted free-booter, who, in 1685, tried to cross the Isthmus of Panama with Captain Sharp. Three times he sailed round the world, and touched at the northern as well as the southern Philippine Islands.

Magellan, Drake and Dampier gave the western world much knowledge of the Far East, but did not remain long enough in the Islands to have any great or lasting influence over the natives. The work of civilizing them was left to Legaspi and the Spanish friars, who were the first real settlers.

In 1565, the Philippines were occupied by an expedition under Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, alcalde of the City of Mexico, who was charged to open a new route to Java and the Southern Islands. On his return voyage he was to examine the ports of the Philippines, and, if expedient, to found a colony there. In any case he was to establish trade with the Islands. The viceroy of Mexico charged him that the friars with the expedition were to be treated with the utmost consideration, "since you are aware that the chief thing sought after by His Majesty is the increase of our holy Catholic faith and the salvation of the souls of those infidels."

Cebu was occupied, and Manila was taken and[Pg 153] made the seat of government. The occupation of the Islands was not exactly by force of arms, for there was no fighting, although they found the islands well populated and the people more or less armed. The natives seemed to recognize and submit to a better government and religion than they had ever known. The reports of the Spaniards of the time speak of the success of small expeditions of perhaps a hundred men, who took over whole provinces. These soldiers were accompanied by Spanish priests, who settled among the people, preaching Christianity in the native tongues. The friars persuaded them to give up their continual feuds and submit to the central authority which the friars represented.

Legaspi brought with him from Mexico four hundred Spanish soldiers. Later eight hundred more arrived, and civilian Spaniards, both married and single, sailed to the Islands as settlers. In 1591, according to the records of Spanish grants, there were 667,612 natives under Spanish rule, and twenty-seven officials to enforce the laws and preserve order. It was reported that in a majority of the grants there was peace, justice and religious instruction. There were Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan friars as well as secular clergy. These[Pg 154] men were not only priests but also fighters and organizers, and did fine work for many years, until long-continued possession of power gradually made the orders corrupt and grasping.

Upon their first arrival, the Spaniards found the people established in small villages, or barangays, where the chief lived surrounded by his slaves and followers. It was considered wise to continue this system, ruling the villages through the local chieftain, whom the Spaniards called cabeza de barangay. Churches were erected, convent houses were built about them, and the natives were urged to gather near by. It was ordered that "elementary schools should be established, in which the Indians will be taught not only Christian doctrine and reading and writing but also arts and trades, so that they may become not only good Christians but also useful citizens."

So at the end of the sixteenth century the Philippines were at peace. The natives were allowed to move from one town to another, but they were required to obtain permission, in order to prevent them from wandering about without religious instruction. The tendency of the Malays is to separate into small groups, and they have never been dwellers in large [Pg 155] towns. The Spanish priests, therefore, found a constant effort necessary to keep them concentrated about the churches "under the bells."

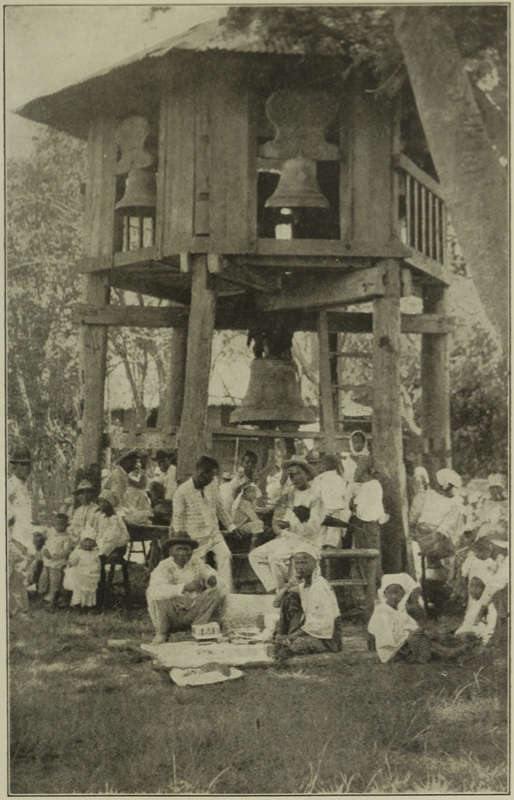

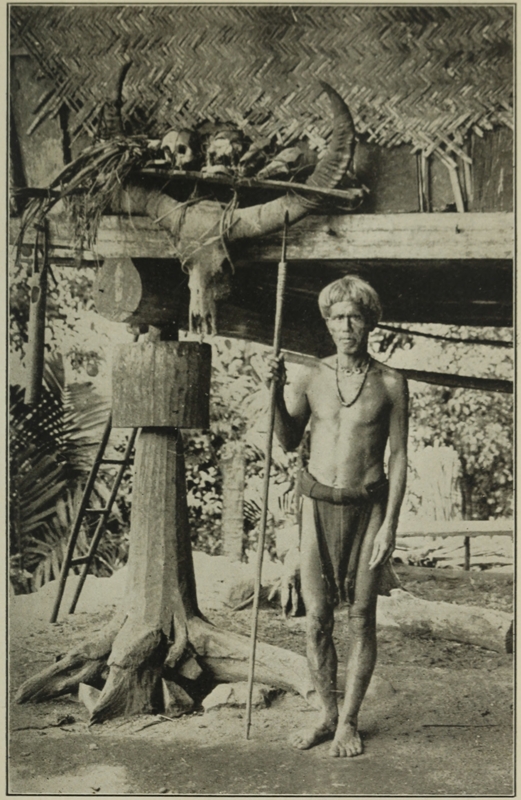

"UNDER THE BELLS."

"UNDER THE BELLS." Until the revolt of 1896, Spain never found it necessary to hold the Islands by armed force; her dominion there was based rather on her conquest of the minds and souls of men. There had been a few uprisings, however, and early in the eighteenth century a Spanish governor and his son were murdered by a mob. But notwithstanding occasional difficulties, in the main there was peace until the civil service of the Philip[Pg 156]pines was assimilated with that of Spain. Then officials became dependent upon their supporters at home, and were changed with every change of the ministry. Some Spaniard writing at the time said that with the opening of the Suez Canal Spanish office holders descended on the Islands like locusts.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Spanish army had grown to 17,859 of all ranks, only 3,005 of whom were Spaniards, and there was a constabulary of over 3,000 officers and men, who were almost entirely natives. The rule of Spain was secured by a native army. There could have been no widespread discontent, or that army would not have remained true to its allegiance, especially as its recruits were obtained by conscription.

The chronicles remind us, however, that the Spaniards did not have things all their own way. In the early days, they were at first friendly with the Chinese, and Mexico carried on a flourishing trade with China by way of Manila until the pirate Li Ma Hong raided the Islands. The Spaniards were on good terms with the Japanese until the latter massacred the Jesuit friars in Japan. When the Shogun Iyeyasu expelled the priests he sent away even those who were caring for the lepers, and as a final insult, he[Pg 157] sent to Manila three junks loaded with lepers, with a letter to the governor general of the Philippines, in which he said that, as the Spanish friars were so anxious to provide for the poor and needy, he sent him a cargo of men who were in truth sore afflicted. Only the ardent appeals of the friars saved these unfortunates and their contaminated vessels from being sunk in Manila Bay. Finally the governor yielded, and these poor creatures were landed and housed in the leper hospital of San Lazaro, which was then established for their reception and which remains to-day.

The Spanish governors were also hampered by the lack of effective support from the older colony of Mexico, which was so much nearer than the home land that they naturally turned to it for aid. One of them wrote pathetically to the King of Spain:

"And for the future ... will your Majesty ordain that Mexico shall furnish what pertains to its part. For, if I ask for troops, they send me twenty men, who die before they arrive here, and none are born here. And if I ask for ammunition, they laugh at me and censure me, and say that I ask impossible things. They retain there the freight money and the duties; and if they should send to this state what is yours,[Pg 158] your Majesty would have to spend but little from your royal patrimony."

The Portuguese were a source of anxiety to the colonists until Portugal fell into the hands of Spain. The Dutch, too, who were growing powerful in the Far East, even took Formosa, which brought them altogether too near, but they were driven out of that island by the great Chinese pirate Koxinga.[13]

From the time of Legaspi to the end of Spanish rule there were occasional attacks upon the Chinese residing in the archipelago, who were never allowed to live in the Islands without exciting protest and dislike, based partly upon religious, partly upon commercial grounds. During the last one hundred years of Spanish supremacy, the greatest danger to their power was the presence of the Chinese. Efforts to [Pg 159]exclude them were never effective or long enduring, and yet it was felt that the men who came as labourers and traders were the advance guard of an innumerable host. In business the Malay has never been the equal of the shrewd Chinaman, and although the latter might be converted and take a Spanish name, yet it was always gravely suspected that a search would find joss sticks smoldering in front of the tutelary deity of commerce hidden behind the image of the Virgin in his chapel.

So the Chinaman, like the Jew in medieval Europe, carried on his trade in constant danger of robbery and murder. This antipathy did not, however, extend to Filipina women, many of whom married the foreigners. Among the leaders in the Filipino insurrection against the United States, Aguinaldo, two of his cabinet, nine of his generals, and many of his more important financial agents were of Chinese descent.

In 1762 the English swooped down upon Manila, but they held the capital only two years, for, by the Treaty of Paris, the lands they had taken were returned to Spain. It is said the English conquest, brief as it was, brought good results to the Islands.

Before going on to the struggle against the[Pg 160] friars, I wish to quote from my father's letters describing his experiences in the Philippines twenty years before American occupation.

"At Sea, December 2, 1878.

"From Manila we went in a boat up a short river, which had its rise in a large lake, about twenty-five miles long, that we crossed in a steamer. I think I never saw such quantities [Pg 161]of two things as were on that lake—namely, ducks and mosquitoes.

"From the lake we continued our journey in two-horse vehicles, like the volantes of Havana, and in these we went from village to village, on our way to the mountains. We were very well treated. The Spanish authorities at Manila provided us with whatever we required. The villages were clusters of thatched huts around a church, and the religion seemed to be a curious mixture of Roman Catholic Christianity and pagan superstition, as I concluded from the style of the pictures with which the churches were adorned. These were chiefly representations of hell and its torments. Devils, with the traditional tails and horns, and armed with pitchforks, were turning over sinners in lakes of burning brimstone....

"We found the natives very musical; they sang and played on a variety of instruments, and they were rather handsome. The women had, without exception, the longest and most luxuriant hair I ever saw in all my travels. You know it is a rare thing among us for a woman to have hair that sweeps the ground, but here the exception is the other way; nearly every woman I saw had hair between five and six feet in length.

[Pg 162]

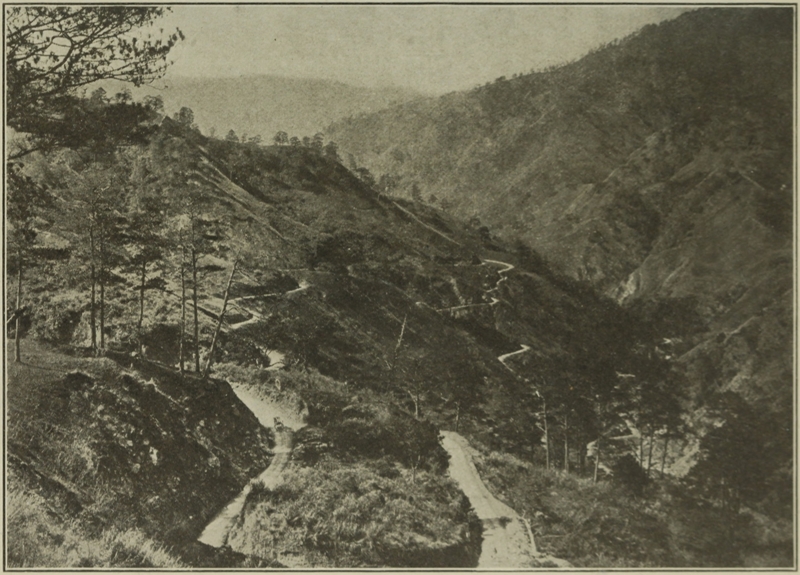

"I was told that back among the mountains there existed tribes whom the Spaniards have never been able to conquer, and no one dares to venture among them, not even the priests. Our road was constantly ascending, and as we advanced toward the interior the scenery became beautiful. Peaks of mountains rose all about us; plains and valleys stretched out, covered with tropical vegetation; picturesque villages, clustering around their churches, were visible here and there; and in the distance were glimpses of the sea, sparkling and bright in the sun.

"I was told of a wonderful ravine among the mountains that was worth seeing and I decided to visit it, especially as it was a favourable time; the river, by which it had to be approached, was then high, and its fifteen cascades, which usually had to be climbed past, dragging the canoe, were reduced to four. I took three natives with me, and we ascended successfully. I have called it a ravine, but a gorge would be a better term, for it is worn directly through the mountain by a large river, and the rock rises up on each side, as sheer and straight as if cut by machinery.

"After I had ascended a certain distance, I stopped for a time to examine all the wild mag[Pg 163]nificence about me. The rocky wall on each side was so high that when I looked up I could see the stars shining in that bright noonday, as if it were night. Huge birds came flapping up the gorge far above my head; and yet they were far below the top of the mountain of rock. I do not know how many feet it rose, but I never saw any precipice where the impression of height was so effectually given—it seemed immense.

"Beneath us was the deep, broad stream, looking very dark in the twilight that such a shadow made, and I could not help feeling awestruck. But the opening of the gorge framed as smiling and cheerful a landscape as could possibly be devised, to contrast with the inner gloom. It was a wide, varied and splendid view of the country beyond, sloping to the distant sea, and all of it as aglow with light and colour as sea and land could be, beneath a tropic sun.

"Descending the river on our way out, I had a characteristic adventure, which will make me satisfied for a time. We had passed two of the rapids in safety, but as we approached the third, the canoe struck on a rock or something in the current, bow on, and swinging round, half filled with water. The natives in the end of the canoe nearest the rock sprang out and clung to the vines which hung over its sides, but the other[Pg 164] man and I went over the fall in the half-swamped canoe, and were wholly at the mercy of the stream, with an unusually good prospect of getting a good deal more of it.

"The fall once passed through, the current drove us toward the shore, if that is what you would call a precipice of rock, running straight down far below the surface of the water. I succeeded in grasping the vines and pulling the canoe after me by my feet. The water was quite close by the rock, and the other two men, crawling down to us, hung on with me, and bailed out the boat till it was safely afloat, and then we went down the rest of the way without accident."

Before the middle of the last century, life in the Philippines must have been, for Spaniards and natives alike, one long period of siesta. The sound of the wars and the passing of governments and kings in Europe must have seemed to these loiterers in a summer garden like the drone of distant bees. After that period conditions changed rapidly. In 1852, the Jesuits returned to the Philippines; in 1868, the reactionary Queen Isabella II fled from Spain, because of the rise of republicanism; in 1869, the Suez Canal was opened. All these events had[Pg 165] their influence, but the return of the Jesuits was of dominating importance.

Throughout the nineteenth century the sole idea of the Tagals was to get rid of the friars, and for several reasons, which I will explain as briefly as possible. The Roman Catholic clergy are divided into regular and secular. Members of the secular clergy are subordinate to the bishops and archbishops, through whom the decrees of the Holy See are promulgated. The regular clergy, monks and friars, are subordinate to provincials elected for comparatively short terms of office by members of their own order. The Jesuits form a group by themselves but belong rather to the regular than the secular.

Over three hundred years after the conversion of the Filipinos, the Spanish monks and friars considered it still unsafe to admit natives into the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. The secular clergy were mostly natives, the regular clergy were Spaniards. Naturally this condition of affairs in time produced friction.

To understand the case in regard to the Jesuits, it is necessary to go back nearly a century. In 1767, the King of Spain issued a decree expelling the Jesuits from his possessions. Their property was confiscated, their schools were closed, and they were treated as enemies of the[Pg 166] state. They had been among the earliest missionaries in the Philippines, and were probably the wealthiest and most influential of all the clergy there. Their departure left no priests for the richest parishes in the provinces of Cavite and Manila, which had been their sphere of influence. The question at once arose as to who would succeed them, and as it happened, the Archbishop of Manila who had to answer it was a member of the secular clergy, a Spanish priest to be sure, but of liberal tendencies. Consequently, he filled the parishes with native priests, who continued to occupy them until the return of the Jesuits.

Now the parish priest was the most influential man in the community. As native priests used this influence to build up the prestige of the seculars, the ecclesiastical feuds which arose became embittered by racial antagonism.

When a royal order was received permitting the return of the Jesuits it became at once necessary to find places for them in the ecclesiastical government. Spain decided that the parishes of Cavite and Manila should be henceforth filled by members of the order of Recollets, who were to transfer their missions in Mindanao to the Jesuits. The Archbishop protested against this increase in the power of the[Pg 167] regular clergy, and the Governor General assembled his council to act upon the protest. All the members of the council who were born in Spain voted against the Archbishop. All those born in the Philippines voted for him. The regulars gained another victory over the seculars; the native was publicly informed that he was not fit to administer the parishes of his own people, and he saw himself definitely assigned to the position of lay brother or of curate. Whatever threads of attachment there had been between the opposing factions broke on the day of that decision, and every native priest from that moment became a center of disaffection and of the propaganda of hatred of the friars. This was perhaps the real beginning of the movement which continued, now secretly, now openly, until it broke out in actual revolt in 1872. The Spaniards put down this uprising of the Tagalogs with such cruelty that they feared a later retaliation, and sought help from the friars. This the friars gave them, in return for added wealth and power, which was granted, of course, at the expense of the vanquished natives.

Worcester writes in one of his earlier books, "During the years 1890-93, while traveling in the archipelago, I everywhere heard the mutter[Pg 168]ings that go before a storm. It was the old story: compulsory military service; taxes too heavy to be borne, and imprisonment or deportation with confiscation of property for those who could not pay them; no justice except for those who could afford to buy it; cruel extortion by the friars in the more secluded districts; wives and daughters ruined; the marriage ceremony too costly a luxury for the poor; the dead refused burial without payment of a substantial sum in advance; no opportunity for education; little encouragement for industry and economy, since to acquire wealth meant to become a target for officials and friars alike; these and a hundred other wrongs had goaded the natives and half-castes until they were stung to desperation."

The dissensions in the Philippines which ended in the rebellion of 1896-7 began with disagreements among the Spaniards themselves. A progressive party arose before which the clerical or conservative party slowly but steadily lost ground, and the legislation of modern Spain was by degrees introduced into the Islands. The country was not able to endure the taxation which would have been necessary to raise the revenues to carry out this legislation. Hence laws which were passed against the advice of[Pg 169] the Spanish clergy in the Philippines were left largely in their hands for execution, not because they were loved or trusted, but because they were the only Spanish functionaries who knew the language and the people and whose residence in the Islands was a permanent one. If the friars had used their power wisely and unselfishly, there would have been no trouble, but they used it too often simply to keep the people down and extort money, for which they gave little return.

By degrees the mestizos took sides. The Chinese mestizos soon grew restive under this priestly government, and aided the progressive Spanish party in Manila. As time passed they had it borne in upon them that revolution might pay.

The insurrection of 1896-7 was planned and carried out under the auspices of a society local to the Philippines, called the "Katipunan," the full title of which may be translated as "Supreme Select Association of the Sons of the People." According to Spanish writers on the subject, it was the outgrowth of a series of associations of Freemasons formed with the expressed purpose of securing reforms in the government of the Philippines, but whose unexpressed and ultimate object was to obtain the[Pg 170] independence of the archipelago. As if to accomplish this purpose, a systematic attack was made on the monastic orders in the Philippines, to undermine their prestige and to destroy their influence upon the great mass of the population. The honorary president of the Katipunan was José Rizal, whose name was used, without his permission, to attract the masses to the movement.

Rizal was born in 1861 not far from Manila. He came of intelligent stock. After his early training at the Jesuit school in Manila and the Dominican university, Rizal went to Spain, where he took high honors at the University of Madrid in medicine and philosophy. Post-graduate work in France and Germany followed.

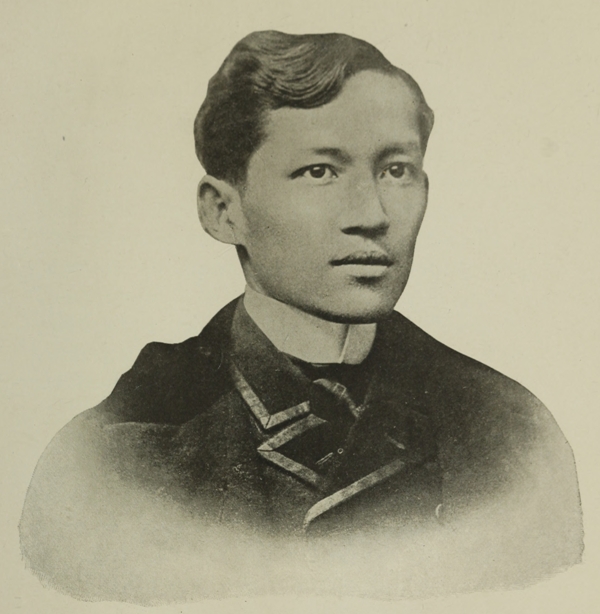

JOSE RIZAL.

JOSE RIZAL. In 1891, Rizal began the practice of medicine in Hongkong. Meanwhile, the Spanish authorities, in their desire to get him into their power, worked upon his feelings by persecuting his mother. The trick was successful, and he returned to Manila, where he was soon arrested, and banished to the island of Mindanao.

The most powerful leader of the insurrection was Andres Bonifacio, a passionate and courageous man of little education. He sent an agent to Dr. Rizal to aid him in escaping from his place of exile and to request him to lead the Katipunan in open revolt. Rizal refused, believing that the Filipinos were not yet ready for independence. Bonifacio resolved to proceed without him.

Bonifacio assured his audience that when he gave the signal the native troops would join them. It was of great importance to the success of his plan that the army, as in 1872, was engaged in operations against the Moros. There were available in Manila only some three hundred Spanish artillery, detachments amounting to four hundred men, including seamen, and two thousand native soldiers. The plot was discovered, but Bonifacio escaped from Manila, and sent out orders for an uprising in that part[Pg 172] of Luzon which had been organized by the Katipunan. Manila was attacked, but the rebels were repulsed. Martial law was proclaimed in eight provinces of Luzon, followed by wholesale executions. Many of those arrested on suspicion "were confined in Fort Santiago, one batch being crowded into a dungeon for which the only ventilation was a grated opening at the top, and one night the sergeant of the guard carelessly spread his sleeping-mat over this, so the next morning some fifty-five asphyxiated corpses were hauled away."

Just before the outbreak, Rizal received permission to join the army in Cuba as surgeon, but on the way there was arrested and brought back to Manila. His fate was now sealed. The trial by court-martial was a farce. On a December day in 1896 he was led to execution.

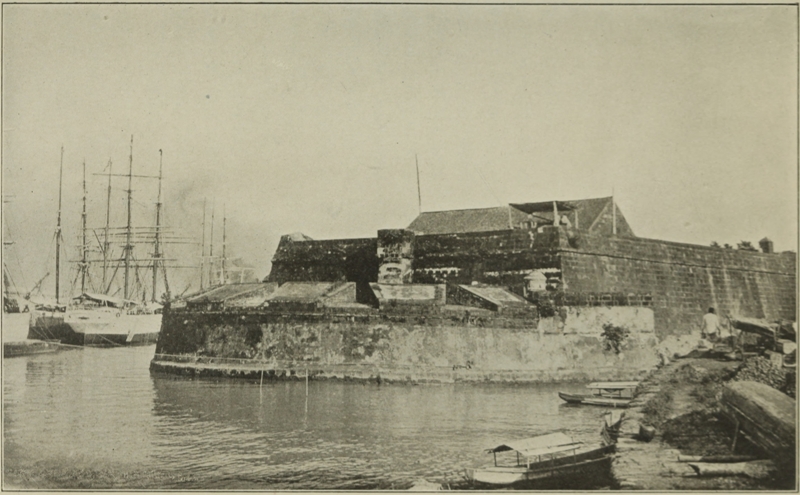

FORT SANTIAGO.

FORT SANTIAGO. The seacoast towns were under the leadership of Emilio Aguinaldo, a young radical, who was already a recognized leader among the local disaffected. The Spaniards had not expected this outbreak in Cavite. Aguinaldo had personally assured the governor of the province of his devotion to Spain, but when fighting began isolated Spanish officers were killed and their families carried into captivity. The difficulties, of the Spaniards were increased by the fact that the defense of Manila and Cavite until reinforcements arrived, would be largely in the hands of native troops, among whom the Katipunan was known to have been at work. But the troops of the old native regiments—the men who for years had followed Spanish officers—were on the whole faithful, and it was largely due to them that Manila and Cavite were held.

The leaders in the insurrection were of that class who called themselves ilustrados, enlightened, a class whose blood is, in almost every case, partly Spanish or partly Chinese. The supremacy of the friars was passing, and men of this class intended to be the heirs to[Pg 174] their domain. The idea of forming a republic and even of adopting the titles appropriate to a republic to designate the functionaries of a Malay despotism was an afterthought.

Reinforcements arrived from Spain, and by June 10, 1897, the insurrection was broken, and Aguinaldo with his remaining adherents had taken refuge at Biacnabato, some sixty miles from Manila. He was now without a rival, for Bonifacio had dared to attempt his life, had been brought before a court-martial, had been condemned to death and had disappeared.

Aguinaldo, who now called himself not only Generalissimo of the Army of Liberation but President of the Revolutionary Government, had adopted guerilla warfare, and the Spanish commands were forced to follow an enemy who was never dangerous to large bodies, but who always was to small ones—an enemy who, wearing no uniform, upon the approach of a large body became peaceful labourers in the fields along the road, but were ready to pick up their rifles or bolos and use them against a small party or a straggler. Still, whatever they had fought for at first, the insurgent leaders were now fighting for their own safety.

The governor general sought in various ways to gain the support of the country. He called[Pg 175] for Filipino volunteers, and, curiously enough, they responded with enthusiasm. The rapidity with which they were recruited was probably largely due to the activity of the friars. This added to the hatred of them felt by the class of natives represented by Aguinaldo.

Between June and December, 1897, the time was spent in an obscure bargaining, the outcome of which was the so-called Treaty of Biacnabato, which Primo de Rivera—the governor general—has stated was merely a promise to pay a money bribe to the insurgents if they would cease a combat in which they had lost hope of success but which they could still prolong to the detriment of the resources and the prestige of Spain.

The result of the bargainings was that Spain agreed to pay eight hundred thousand Mexican dollars for the surrender of Aguinaldo and his principal leaders and the arms and ammunition in their possession. An amnesty was proclaimed. Aguinaldo and his leaders were sent to Hongkong under escort, where they declared themselves loyal Spanish subjects. Primo de Rivera returned to Spain. As he received in return for the money only about two hundred rifles and a little ammunition, it is not probable that he made any of the promises of[Pg 176] changes in the government of the archipelago which the Filipinos have insistently stated since then were the real objects of the agreement.

Whatever may have been the true motives which actuated the Spanish governor general in adopting this method of terminating a successful campaign, he succeeded in purchasing only an armistice and not a peace. On January 23, 1898, a Te Deum was sung in the cathedral of Manila to mark the reëstablishment of peace in the archipelago.

The insurgent leaders had been bought off and their followers had surrendered their arms.

As Spanish dominion in the Philippines was now about to close, let us stop a moment to inquire what it had brought to the Islands. It may have been hard and utterly unprogressive, but it turned the tribes of Luzon and the Visayas from tribal feuds and slave-raiding expeditions to agriculture.

To accomplish these results required untiring energy and a high enthusiasm among the missionaries. They had lived among savages, speaking their tongue, until they had almost forgotten their own. Spain had ceased to be everything to them; their order was their country. Spanish officials came and went, but the ministers of the Church remained, and as they[Pg 177] grew to be the interpreters of the wants of the people, in many cases their protectors against spoliation, power fell into their hands. It is rather interesting to learn that in 1619, in the reign of Philip III, it was proposed to abandon the Philippines on account of their useless expense to Spain, but a delegation of friars from the Islands implored him not to abandon the twenty thousand Christians they had converted, and the order was countermanded.

Spanish dominion left the people Christians, whereas, if the Islands had not been occupied by Spain, their people would in all probability to-day be Mohammedan. The point of view of the Spanish friars may not be ours, but when their efforts are judged by the good rather than the evil results, it can still be said that Spain gave Christianity and a long term of peace to the Philippine archipelago. The Filipinos are the only Christian Asiatics.

But Philippine history was to take an unexpected turn. The Spanish-American war broke out, and a new factor appeared upon the scene in the shape of Commodore Dewey and his fleet. We all know the story of the battle of Manila Bay, but we may just recall it briefly.

It was the night of April 30, 1898, that the American Asiatic squadron, which had received[Pg 178] its orders at Hongkong, arrived off the Philippines. They took a look first into Subig Bay, but seeing no enemy, they made their way into Manila Bay by the Boca Grande entrance. There were rumours of mines in the channel and big guns in the forts, but Dewey took the chance, and the fleet steamed in at night. The ships formed two columns, the fighting ships all in one line, and the auxiliary vessels about twelve hundred yards behind. They moved at the rate of their slowest vessel.

Black thunder clouds at times obscured even the crescent moon that partially lighted their course, but occasional lightning flashes gave the bold Americans a glimpse of frowning Corregidor and the sentinel rock of El Fraile. The ships were dark except for one white light at the stern of each as a guide to the vessel next in line. As the Olympia turned toward El Fraile her light was seen by a Spanish sentry. A sheet of flame from the smokestack of the McCulloch, a revenue cutter attached to the fleet, also betrayed its presence to the enemy at the same moment. El Fraile and a battery on the south shore of the bay at once opened fire, which was returned by the ships to such good purpose that the battery was silenced in three minutes. Slowly, steadily, Dewey's ships steamed on, and[Pg 179] at dawn discovered the gray Spanish vessels lying in front of the naval arsenal at Cavite, over on the distant shore to the right. Admiral Montojo's flagship, the Reina Cristina, and the Castilla, and a number of smaller vessels, formed a curved line of battle, which was protected in a measure by the shore batteries. The Spaniards had one more ship than the Americans, but the latter had bigger guns.

Silently the American squadron advanced across the bay, with the Stars and Stripes flying from every ship. At quarter past five on the morning of May 1st, the Spanish ships fired their first shots. When less than six thousand yards from their line, Dewey gave the famous order to Captain Gridley, in command of the Olympia: "You may fire when you're ready, Gridley."

Two hours later, the Reina Cristina had been burned, the Castilla was on fire, and all but one of the other Spanish vessels were abandoned and sunk. Dewey gave his men time for breakfast and a little rest, then shelled and silenced the batteries at Cavite. Soon after noon the Spaniards surrendered, having lost 381 men and ten war vessels. Seven Americans were slightly wounded, but none were killed. So ended this famous battle.

[Pg 180]

CHAPTER III

INSURRECTION

dmiral Dewey took a great liking to General Anderson, "Fighting Tom" (L.'s cousin), the first military officer to command the American forces in the Philippines. On one occasion the Admiral fired a salute well after sundown (contrary to naval regulations) to compliment him on his promotion to the rank of major general, and scared the wits out of some of the good people ashore. General Anderson has given me a few notes about his experiences at that time, which are of special interest.

"When in the latter part of April, 1898, I received an order relieving me from duty in Alaska and ordering me to the Philippines, I was engaged in rescuing a lot of people who had been buried by an avalanche in the Chilcoot Pass. I took my regiment at once to San Francisco, and there received an order placing me in command of the first military expedition to the Philippines. This was the first American[Pg 181] army that ever crossed an ocean. We were given only two days for preparation. We were not given a wagon, cart, ambulance, or a single army mule, nor boats with which to land our men. I received fifty thousand dollars in silver and was ordered to render what assistance I could. I had never heard of Aguinaldo at that time, and all I knew of the Philippines was that they were famous for hemp, earthquakes, tropical diseases and rebellion."We stopped at Honolulu on the way over, although the Hawaiian Islands had not been annexed. The Kanakas received us with enthusiasm and assured us that the place was a paradise before the coming of the missionaries and mosquitoes. From there we went to Guam, where we found nude natives singing 'Lucy Long' and 'Old Dan Tucker,' songs they had learned from American sailors.

"When we reached Cavite the last day of June, Admiral Dewey asked me to go ashore and call on Aguinaldo, who, he assured me, was a native chief of great influence. Our call was to have been entirely informal, but when we approached the house of the Dictator we found a barefooted band in full blare, the bass-drummer after the rule of the country being the leader. The stairway leading to Aguinaldo's[Pg 182] apartment was lined on either side by a strange assortment of Filipino warriors. The Chief himself was a small man in a very long-tailed frock coat, and in his hand he held a collapsible opera hat. I saw him many times afterward and always thus provided. He asked me at once if I could recognize his assumption. This I could not do, so when a few days later I invited him to attend our first Fourth of July he declined. He further showed his displeasure by failing to be present at the first dinner to which we American officers were invited. There for the first time we met Filipina ladies. They were bare as to their shoulders, yet in some mysterious way their dresses remained well in place. In dancing there was a continuous shuffling on the floor because their slippers only half covered their light fantastics, rendering them more agile than graceful.

A GROUP OF FILIPINA LADIES.

A GROUP OF FILIPINA LADIES. "Soon after I got to Cavite, I was invited with the officers of my staff to attend a dinner given in my honour. At the symposium I was [Pg 183] asked to state the principles upon which the American government was founded. I answered, 'The consent of the governed, and majority rule.' Buencamino, the toastmaster, replied, 'We will baptize ourselves to that sentiment,' upon which he emptied his champagne glass on his head. The others likewise wasted their good wine.

"When General Merritt arrived he first came ashore at a village behind the line we had established where Aguinaldo was making his headquarters. Rain was falling in torrents at the time, but Aguinaldo, who must have known of the presence of the new Governor General, failed to ask him to take shelter in his headquarters. Naturally General Merritt was indignant and directed that thereafter any necessary business should be conducted through me. This placed me in a very disagreeable position. At first I thought I could conciliate and use the Filipinos against the Spaniards, but General Merritt brought an order from President McKinley directing that we should only recognize the Filipinos as rebellious subjects of Spain. Aguinaldo reproached me bitterly for my change of conduct toward him, but because of my orders I could not do otherwise, nor could I explain the cause.[Pg 184]

"We soon drifted into open hostility. I found but one man who appeared to understand the situation, and he was the much hated Archbishop Nozaleda. After we took Manila he invited me to come to see him. He remarked in the course of our conversation that when we took the city by storm he expected to see our soldiers kill the men and children and violate the women. But instead he praised us for having maintained perfect order. For reply I quoted the Latin, 'Parcere subjectis, et debellare superbos.' Which prompted him to say in Spanish to a Jesuit priest, 'Why, these people seem to be civilized.' To which the Jesuit replied, 'Yes, we have some colleges in their country.'

"The statement that we seemed to be civilized calls for an explanation. I found many Filipinos feared American rule might prove more severe on them than the Spanish control. In a school book that I glanced at in a Spanish school was the enlightening statement that the Americans were a cruel people who had exterminated the entire Indian population of North America."

The battle of Manila Bay was fought and won, as we well remember, on May Day. Through the kind offices of the British consul the Spanish admiral came to an understanding with Dewey.[Pg 185] Surgeons were sent ashore to assist in the care of the wounded Spaniards, and sailors to act as police. The cable was cut, and the blockade was carried into effect at once. The foreign population was allowed to leave for China. German men-of-war kept arriving in the harbour, until there were five in all. It was known that Germany sympathized with Spain, and only the timely arrival of some friendly English ships, and the trenchant diplomacy of our admiral, prevented trouble.

All the rest of that month, and the next, and still the next, the fleet lay at anchor, threatening the city with its guns, but making no effort to take it. The people lived in constant fear of bombardment from the ships which they could so plainly see from the Luneta on their evening promenades. But they could not escape, for Aguinaldo's forces lay encamped behind them in the suburbs. In fact, the refugees were seeking safety within the walls of the city, instead of fleeing from it, for while they had no love for the Spaniards, and were fellow countrymen of the rebel chieftain, they preferred to take their chances of bombardment rather than risk his method of "peaceful occupation."

Of course there was no coöperation between the Americans and the Filipinos, although both[Pg 186] wanted the same thing and each played somewhat into the other's hand. Admiral Dewey refused to give Aguinaldo any naval aid, and the insurrectos on at least two occasions found it profitable to betray our plans to the common enemy.

The delay in taking the city was caused by Dewey's shortage of troops. He could have taken it at any time, but could not have occupied it. The Spanish commander made little attempt at defense. A formal attack on one of the forts satisfied the demands of honour. When the city surrendered, on August 13th, the Americans were in the difficult position of guarding thirteen thousand Spanish soldiers, of keeping at bay some fourteen thousand plunder-mad Filipinos, and of policing a city of two hundred thousand people—all with some ten thousand men!

The way in which it was accomplished is in effective contrast with European methods. When our troops broke the line of trenches encircling Manila they pressed quickly forward through the residence district to the old walled town, which housed the governmental departments of the city. Here they halted in long lines, resting calmly on their arms until the articles of capitulation were signed. It took but[Pg 187] an hour or so to arrange for the disposition of our troops among the various barracks and for the removal of the disarmed Spanish garrison to the designated places of confinement. Then command was passed along by mounted officers for the several regiments to proceed to their quarters for the night. In columns of four they marched off with the easy swing and unconcern of troops on practice march. A thin cordon of sentinels appeared at easy hailing distance along the principal streets, and the task was accomplished.

By noon next day they had a stability as great as though they had been there for years. Not a woman was molested, not a man insulted, and the children on the street were romping with added zest to show off before their new-found friends. The banks felt safe to open their vaults, and the merchants found a healthily rising market. The ships blockaded and idling at anchor in the harbour discharged their cargoes, the customs duties being assessed according to the Spanish tariff by bright young volunteers, aided by interpreters. The streets were cleaned of their accumulated filth, and the courts of law were opened. All this was done under General Anderson's command, and it seems to me is much to his credit.[Pg 188]

A daughter of General Anderson's, who was there at the time with her father, writes: "Days of intense anxiety followed the opening of hostilities. The Filipinos were pushed back more and more, but we feared treachery within the city. We heard that they were going to poison our water supply, that they were going to rise and bolo us all, that every servant had his secret instructions. Also, that Manila was to be burned. There proved to be something in this, for twice fires were started and gained some headway, and we women were banished to the transports again."

Aguinaldo had demanded at least joint occupation of the city, and his full share of the loot as a reward for services rendered. We can imagine his disgust at being told that Americans did not loot, and that they intended to hold the city themselves. If there had been no other reason for refusing him, the conduct of his troops in the suburbs would have furnished a sufficient one, for they were utterly beyond control, assaulting and plundering their own brother Filipinos and neutral foreigners, as well as Spaniards, and torturing their prisoners. But this refusal, justifiable as it certainly was, marked the real beginning of the insurrection[Pg 189] against American rule, though there was no immediate outbreak.

Aguinaldo was a mestizo school teacher when, in 1896, he became leader of the insurrection against Spain. The money with which Spain hoped to purchase peace was to be paid in three instalments, the principal condition being that the Filipino leaders should leave the Islands. This they did, going to Hongkong, where the first instalment was promptly deposited in a bank. The second instalment, to Aguinaldo's great disgust, was paid over to Filipinos left in the Islands, and the last one was not paid at all. This was just as well for him, because his fellow insurrectionists were already demanding of him an accounting for the funds in Hongkong, and had him summoned to court for the purpose. This proceeding he wisely avoided by leaving for Europe in disguise.

He got only as far as Singapore, however, for there—in April of '98—he heard of the probability of American interference in the Islands and interviewed our consul. The go-between for this interview was an unscrupulous interpreter, whose intrigues were destined to have far-reaching effects for us. It has been charged that both our consul at Singapore and[Pg 190] the one at Hongkong committed this nation to a policy favouring Philippine independence, but the whole question of American pledges finally resolves itself into a choice between the word of an American admiral and a Chinese mestizo.

When Spain had failed to pay over to Aguinaldo the balance of the peace money, he had promptly gone to work to organize another revolution from the safe harbourage of Hongkong. His flight to Singapore had interrupted this, but now, with the Americans so conspicuously there to "help," it was a simple matter to put his plans in operation.

A month after the battle of Manila Bay Aguinaldo proclaimed himself "president" (in reality military dictator) of the "Filipino Republic." But this republic existed only on paper. Dewey accurately states the condition of affairs when he says, "Our fleet had destroyed the only government there was, and there was no other government; there was a reign of terror throughout the Philippines, looting, robbing, murdering." A form of municipal election was held, but if a candidate not favoured by the insurgents was elected, he was at once deposed. One candidate won his election by threatening to kill any one who got the office in his place. Persons "contrary minded" were not allowed [Pg 191] to vote. These happenings hardly suggest a republican form of government, but they are typical of conditions at that time.

AGUINALDO'S PALACE AT MALOLOS.

AGUINALDO'S PALACE AT MALOLOS. Meanwhile his lack of recognition by the Americans, and his exclusion from the spoils of war, so far as Manila was concerned, showed him that his only hope of achieving his ambitions lay in driving these interlopers from the Islands. But for the time being, while awaiting a propitious moment for attack, he occupied himself and his men by conquering the Spaniards in the outlying provinces. Since there was no coöperation among the Spanish forces, he was quite successful. Having proclaimed the republic with himself at the head, he felt justified in maintaining, with the aid of his booty, a truly regal state in his palace at Malolos, aping the forms and ceremonies of the Spanish governors in Manila.

As fast as Church property, or property belonging to Spaniards, fell into his hands, it was[Pg 192] confiscated and turned over to the State—if Aguinaldo can be considered the State. His houses and those of his generals were furnished from Spanish possessions, all title deeds were systematically destroyed or hidden, and administrators were appointed for the property.

At the beginning of the new year (1899), he turned his attention to the Americans, and Manila. Because our forces seemed reluctant to fight, the Filipinos, like the Mexicans to-day, believed that they must be cowards and afraid to meet them. A Mexican paper has recently told its readers what a simple matter it would be, if war were declared, for their troops to cross the border and crush such slight opposition as may be offered to the capture of Washington. So it is no wonder that the Filipinos felt confident of success, especially after their victories over the Spaniards in the outlying regions.