Kanaka Maoli vs. Identity Thieves- Territory turned State with Oppositions documented, Pirates, Pillagers, Squatters, Justice Fails Injuring Our People...…

Review by Amelia Gora (2018) a Royal person

The following are some of the examples of the past and the ongoing injuries that our people have faced, are faced with by Aliens who did premeditate the criminal assumption of our Queen's assets, lands, etc. along with disregard for rule of law over time.

Nice to see the many defenders of our Hawaiian Kingdom whose names shall forever be remembered in our history, our thoughts, our prayers, etc.

Thanks to current U.S. President Donald Trump, he abides by rule of law and the U.S. Constitution.

The following are listed chronologically and the references are also listed below:

1893 -

Opposition to treasonous persons, conspirator's documented by Queen Liliuokalani after their planned premeditation, fraudulent set up with the help of the United States.

References:

https://iolani-theroyalhawk.blogspot.com/2018/12/hawaiian-kingdom-legal-directive-no.html

Hawaiian Kingdom Legal Directive No. 2018 - 1226 Evidence of Concerted Premeditation, Fraud, Piracy/Piracies Against Our Royal Families Researched and Documented

1897 -

Anti-Annexation/Kue Petition by 20,000+ supporters of Queen Liliuokalani:

Annexation of Hawaii | University of Hawaii at Manoa Library

The Annexation Of Hawaii: A Collection Of Documents These documents were scanned and are offered in image and/or PDF format for viewing and printing, in …

1959 -

Opposition to Statehood documented by Kamehameha descendants Harold Abel Cathcart supported by his cousin Mele Keawe Kauweloa.

Reference: Court records, Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii

1968 -

Oppositions to Mauna Kea Telescope recorded and continues today:

Opposition to the Mauna Kea Observatories - Wikipedia

- Opposition to the Mauna Kea Observatories has existed since the first telescope was built in the late 1960s. Originally part of research begun by Gerard Kuiper of the University of Arizona, the site has expanded into the world's largest observatory for infrared and submillimeter telescopes. Opposition to the telescope from residents in the city of Hilo, Hawaii were concerned about the visual appearance of the mountain and Native Hawaiians voiced concerns over the site being sacred to the Hawaiia

Mauna Kea Observatories - Wikipedia

Mauna Kea Observatories seen from the base of Mauna Kea The altitude and isolation in the middle of the Pacific Ocean makes Mauna Kea one of the best locations on earth for ground-based astronomy. It is an ideal location for submillimeter, infrared and optical observations.Images of telescope mauna kea oppositions

bing.com/imagesNative Hawaiians Lead Opposition to New Mauna Kea ...

Hawaii's Telescope Controversy Is the Latest in a Long ...

-

https://www.hawaii.edu/offices/bor/regular/testimony/201504161130/4...proposed land use will cause substantial adverse and detrimental impact to Mauna Kea. HAR §13-5-30. The unique characteristics of this sacred site will NOT be preserved and the land use will be materially detrimental to the public health, safety and welfare. Id. The size of the project will FOREVER change the natural landscape of Mauna Kea.

Mauna Kea telescope, world's biggest, closer to completion ...

VIDEO: TMT Opposition Stakes Out Mauna Kea

Mauna Kea | Mauna Kea FAQ

Telescopes on Mauna Kea . Question: What is the history of telescopes on Mauna Kea? Answer: In 1968, the State of Hawai‘i, through the BLNR, entered into a lease with the University of Hawai‘i (UH) for the Mauna Kea Science Reserve (MKSR), which is comprised of 11,288 acres of land. The MKSR covers all land on Mauna Kea above the 12,000 foot elevation, except for certain portions that lie within the …

"

TMT: THE MOTHER OF ALL MILITARY SURVEILLANCE TECHNOLOGIES

Below is a screen shot from the TMT website that states, under “Facts and Rumors:” “The TMT is a purely scientific endeavor, and managed entirely by the university partners. There is no connection at all to the military.”

Is the claim of no military connection to this telescope honest, or treasonous?

According to University of Hawaii officials, no one presented any viable arguments that the TMT risked people’s health and safety. According to Hawaii Governor Ige, planners spent 7 years investigating and justifying the “non-military” project through open public discussions, all the time misrepresenting the material fact that the U.S. and China both maintain substantial military interests in the TMT, and that the safety and security of the American people is actually at stake if this project moves forward as planned.

Pull the telescope apart and you will discover the lies. TMT’s main components are certifiably military, and more importantly, their military implications and planned operations are not only apparent, but dooming.

At the heart of this military undertaking, this largest ground based telescope in history, is the principle technology called adaptive optics." read more at the above link.

1969 - Kalama Valley and others initiative

Soli Niheu:

"We organized the residents of Kalama and as a result, people like Moose Lui, Mama Lui, George Santos, and the Richards family (Black and Ann) played key roles in the struggle. We also had support from some of the local groups, aside from the House. One, for example, was a group called Concerned Locals for Peace with the family of Nick Goodness. Others were some church groups from Aina Haina and Niu Valley, and, of course, Marion and John Kelly also supported that struggle. Eventually more groups came to support."

Reference: http://www2.hawaii.edu/~aoude/ES350/SPIH_vol39/08Niheu.pdf

Kue - Honolulu Magazine - November 2004 - Hawaii

Resistance Notes 1969-1970 | i L i n d

There is a very good essay on the significance of the Kalama Valley struggle with almost that exact title, “The Birth of the Modern Hawaiian Movement: Kalama Valley, O’ahu.” It was written by Haunani Kay Trask. (I have not always agreed with Haunani.

"It all started in Kalama Valley in 1971. When George Santos, an area pig farmer, refused to leave in the face of planned development by Bishop Estate, his stand struck a chord with people, and the valley became the focal point for activist groups such as Kokua Hawai'i. At the time this photo was taken, access to the valley had been restricted by activists and the few remaining residents, and the atmosphere inside was tense. Above, activist Kalani Ohelo gives an impromptu salute."

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

1971 -

"March 1971 The drama of the Kalama Valley evictions captured the popular imagination, bringing together organizations that might not have otherwise collaborated. For this protest at the State Capitol, at left, Save Our Surf, originally founded to preserve surf sites, joined forces with activists from Kokua Kalama. Protesters were generally respectful, staying clear of the roped-off artwork in the center of the rotunda. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

Kokua Hawaii

Keaulana, et. al. Families fighting evictions in Kalama Valley - 32 arrested.

Hawaii News

Activist Kalani Ohelo, 67, was at forefront of Hawaiian Renaissance

ADVERTISING

Clyde Maurice “Kalani” Ohelo, who grew up in a public housing project in Palolo and became an early symbol of the Native Hawaiian political movement in the 1970s, died April 7 of diabetes-related illnesses at his home in Waimanalo. He was 67.

Ohelo was among 32 people arrested May 11, 1971, for protesting evictions in Kalama Valley — a bellwether of the Hawaiian Renaissance.

Former Hawaii Gov. John Waihee said Ohelo was an articulate and effective speaker.

“He was up from the streets. He could describe what life was,” Waihee said.

Lawrence Kamakawiwoole, a friend of Ohelo’s who taught ethnic studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, said, “He overcame a lot health-wise, and people really listened to what he had to say.”

Born blind, with club feet and a cleft palate, on July 8, 1950, his family said Ohelo’s vision was restored at age 5 after his grandparents took him to a church service in Kalihi where ministers prayed for healing miracles.

In prior interviews, Ohelo recalled how he read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica while recovering at home from several corrective surgeries and undergoing physical therapy. He developed his verbal skills through speech therapy.

As a teenager living in low-income housing in Palolo, he was recruited by VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) to motivate high school dropouts to obtain a high school equilavency diploma, or GED. Ohelo was paid a stipend of $80 a month to become a community organizer, which is how he came to meet other activists such as the late John Kelly of Save Our Surf, Randy Kalahiki of Key Canteen, and Kamakawiwoole, who was organizing Kokua Hawaii to fight the evictions in Kalama Valley.

Kamakawiwoole said he and Ohelo were frequently invited to speak to various groups, including prison inmates, about the Kalama Valley struggle.

“Kalani knew how to speak to those who lived on the edge of society. He was very bright intellectually,” Kamakawiwoole said. “He came from that background.”

Kokua Hawaii helped to stop several evictions in minority communities, including Ota Camp in Waipahu and Waiahole-Waikane in Windward Oahu, and also led a sit-in to preserve ethnic studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa in 1972.

Ohelo is survived by his wife Radine Kawahine Kamakea-Ohelo; his children, Atta Ohelo, Kamaluonalani Williams, Sanoe Murry, Ryan Kamakea, Pamai Fita, Oheloula Hewett, Ahonui Ohelo, Ku‘ike Kamakea-Ohelo and Kaleopa‘a Kamakea-Ohelo; 15 grandchildren and a great-grandaughter.

Services are scheduled for 10:30 a.m. April 28 at Windward Community College in Hale A‘o.

Reference: https://www.staradvertiser.com/2018/04/15/hawaii-news/activist-kalani-ohelo-67-was-at-forefront-of-hawaiian-renaissance/Kekoolani Genealogy of the Descendants of the Ruling ...

HALA IA PUA ALII KAMEHAMEHA This Kamehameha Chiefly Offspring Is Gone (Moses Keaulana) Moses Keaulana was born in Koleaka, Honolulu, in 1876; he had reached the age of 43 and more. Here is his genealogy. Kamehameha the Conqueror is the one who married Kauhilanimaka and was born Kahiwa Kanekapolei**.

Laverne Ka’anohiokala Keaulana Lui « Honolulu Hawaii ...

She was born in Kalama Valley. She is survived by sons Marc and Wayne Spatz, Dane and T.R. Ireland, and Luke Anthony Keaulana; daughters Michelle Ireland and Shanna Arthur; hanai daughter Desire’e Luana Shortt; brothers Moses Keaulana and Joseph Lui; sister Moana Keaulana-Dyball; and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

John Kelly of Save Our Surf,

Randy Kalahiki of Key Canteen,

Kamakawiwoole,

1972

"April 23, 1972Activist Terrilee Kekoolani denounces a proposed development at Wawamalu (Sandy Beach), which would have built between 5,000 and 7,000 upscale houses near the popular fishing and surfing spot."

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

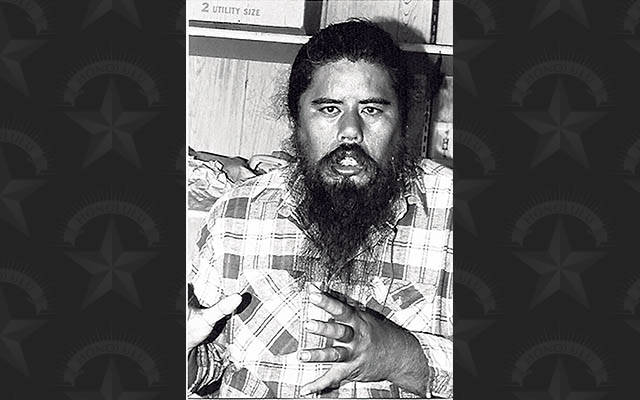

"1973George Helm, pictured here without his iconic beard, became one of the Hawaiian movement's most prominent figures, thanks to his music career and his activism with the Protect Kahoolawe Ohana. He participated in the group's Kahoolawe protest landings, and was lost at sea during one such trip in 1977. The object of Helm's political crusade has been realized-the Navy finally completed its handover of Kaho'olawe in April 2004, after a 10-year, $460-million cleanup. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

1975

"May 1975A property dispute goes up in flames on Mokauea Island, off Sand Island. The state, frustrated with the repeated eviction and return of a resident group of fishermen on the island, hired a contractor to burn down the makeshift houses in an attempt to permanently evict them. Here, Mokauea resident Billy Molale brings Greevy and SOS activists John Kelly, Antonio Andres and Lorna Omori in for a closer look. The families were allowed to return to the island a year later under a long-term lease. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

1976

Protect Kahoolawe Ohana

Reference:

http://uluulu.hawaii.edu/documenting-activism-the-early-days-of-the-native-hawaiian-movement

1977

"

May 1977

Another source of anger for Hawaiians was the military's use of Kaholawe as a bombing range. Hawaiian grassroots organizations such as the Protect Kahoolawe Ohana protested by landing on the island in defiance of no trespassing orders and symbolically reoccupying the land. These men in traditional Hawaiian gourd headpieces stand outside the federal court building in support of their friends inside, on trial for criminal trespassing. "

Another source of anger for Hawaiians was the military's use of Kaholawe as a bombing range. Hawaiian grassroots organizations such as the Protect Kahoolawe Ohana protested by landing on the island in defiance of no trespassing orders and symbolically reoccupying the land. These men in traditional Hawaiian gourd headpieces stand outside the federal court building in support of their friends inside, on trial for criminal trespassing. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

"Nov. 10, 1979This unidentified woman lived in a ramshackle shelter in the fishing settlement on Sand Island. Her house was bulldozed by the state less than three months after this photo was taken. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

1980

"Jan. 1980

By 1979, Sand Island had become home to a rapidly growing settlement of fishermen and other locals, who claimed it as their birthright, much to the dismay of the state. Although the island was artificially constructed between 1940 and 1945, the source of the coral dredgings, the Keehi Lagoon area, was part of the ceded lands. The state was not impressed with the argument, and after repeated eviction notices, it bulldozed about 135 houses on Sand Island, on Jan. 23, 1980, arresting those who refused to leave their houses. "

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

"An unidentified man stands outside Iolani Palace on the 100th anniversary of the United States' annexation of Hawaii. As the Hawaiian sovereignty movement has developed and matured, the focus of protest demonstrations has shifted from the State Capitol to Iolani Palace, the Hawaiian monarchy's last seat of government. "

"Jan. 1993

By 1993, the anti-eviction efforts and other land disputes of the past two decades had helped unite and organize the Hawaiian community, and the focus of Hawaiian activists had shifted to the larger issue of Hawaiian sovereignty."

Many Hawaiians/kanaka maoli including "Ka Lahui Hawaii, one of the biggest grassroots sovereignty organizations, commemorated the 100th anniversary} of the 1893 usurpation of the Hawaiian monarchy by marching to 'Iolani Palace" from various locations such as the Royal Mausoleum and other areas surrounding the Palace.

About 10,000 were in attendance. Included in the processions were large diesel trucks circling the city blocks blasting their horns in tribute to the large gathering.

On that day our people were united.

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/ and

Research/observation by researchers including myself and others.

1996

"June 1996Greevy began documenting the beach community at Makua in 1996, when the state announced plans for eviction. He writes, "Some residents were hesitant to be photographed or have their humble living quarters pictured. This resident, Barbara Avelino, was very proud and quite willing for me to make an image of her and her home."

Reference: http://www.honolulumagazine.com/Honolulu-Magazine/November-2004/Kuae/

Hawaiian dies during eviction - INDEPENDENT & SOVEREIGN

ANAHOLA FAMILY LOSES FATHER AS WELL AS RIGHT TO LAND - …

December 17, 1996 - Affidavit/Lien filed Document No. 96-177455 (281 pages) at the Bureau of Conveyances, Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii which includes genealogies, Crown Land owners names, genocide evidence, premeditation, frauds, evidence, etc.

Many other Affidavits/Liens filed.

2015

Haleakala Telescope Oppositions:

At least 8 protesters arrested at summit of Haleakala - KHNL

www.hawaiinewsnow.com/.../29840248/opponents-of-haleakala-telescope...At the Central Maui Baseyard about 150 people have gathered in opposition of the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope that's currently being built on the summit of Haleakala. …- Reference: http://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/29840248/opponents-of-haleakala-telescope-construction-attempt-another-blockade/

Hawaiian Opposition to Telescope – Sierra Club Maui Group

(from the Kilakila O Haleakala website) ‘The law of Aloha is in the land.’ Kealoha Pisciotta. Respect for Kanaka Maoli Spiritual Practices. Panelists explained that from a kanaka maoli perspective, the summit of Haleakala is considered ‘wao akua,’or the realm of the gods.Solar Telescope - Haleakala - Kula Community Association

143' Solar Telescope on Haleakala Summit Other Related Content The final EIS contains much information on the Solar Telescope's configuration, benefits and impacts: visual, wildlife, National Park, upcountry traffic, Hawaiian culture, noise, etc.Dozens protest against massive telescope being built atop ...

Most Powerful Solar Telescope on Earth Rises Atop Hawaiian ...

Hawaii's Telescope Controversy Is the Latest in a Long ...

What’s Astronomy’s Future in Hawaii – Hawaii Business Magazine

Native Hawaiians and others opposed to the massive Thirty Meter Telescope gathered near the 9,000-foot mark, their encampment near Hale Pohaku, the small campus where observatory workers stay when they’re not at the summit. In March, the protesters blocked the …

Kanaka Maoli Reject Obama's move to claim Hawaiians to be other than a separate nation, etc. through the Minister of Interior.

Reference: http://iolani-theroyalhawk.blogspot.com/2016/09/no-matter-how-much-lipstick-you-put-on.html

2017

Mormon's are Not the land owners. Dawn Wasson a Kamehameha descendant opposed over time.

Royal person(s) including Dawn Wasson NOT Subject to the ...

Feb 16, 2017 · The First Circuit Court of Hawaii and Hawaii Reserves Inc. and Property Reserves Inc., business entities of the LDS Mormon church, made a decision to make claim to Kuleana lands in Laie.

2018

Present and Ongoing issues:

U.S. President Cleveland Gave Hawaii back twice (2x) to Queen Liliuokalani

http://iolani-theroyalhawk.blogspot.com/2017/10/us-president-cleveland-gave-hawaii-back.html

Premeditation documented, John Foster - Secretary of State documents U.S. Presidents, Secretary of States, Generals, etc. and he orchestrated, directed the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani in 1893

References: https://iolani-theroyalhawk.blogspot.com/2018/12/hawaiian-kingdom-legal-directive-no.html etc.

-

https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/Chang_Ltr_to_Holder.pdfhereby countersigns Professor Williamson Chang’s reporting of the commission of felonies in accordance with §4—Misprision of felony, Title 18 United States Code, that provides: “Whoever, having knowledge of the actual commission of a felony cognizable by a court of the United States, conceals and does not as soon

-

blog.hawaii.edu/aplpj/files/2015/09/APLPJ_16_2_Chang.pdf2015 Chang 73 “Great Debate to Save the Older America.”6 Yet, those American voices of opposition in 1898 have long been forgotten. Despite being such a major event, the debate over annexation, and the views of those who stood in opposition, have virtually disappeared from American history. 7

-

https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/35643/...JUDICIAL TAKINGS: ROBINSON V ARIYOSHI REVISITED Williamson B.C. Chang* I. INTRODUCTION The Hawai'i experience in terms of judicial takings is of national significance.

-

https://www.hawaii.edu/offices/bor/regular/testimony/201504161130/4...Testimony and Appendix of Williamson B.C. Chang, Professor of Law, University of Hawaii at Manoa, William S. Richardson School of Law, on “The Management of Mauna Kea and the Mauna Kea Science Reserve,” April 16, 2015, 11:30, University of Hawaii at Hilo.

-

https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/.../1/IndigenousValuesLOS.pdfIndigenous Values and the Law of the Sea Williamson Chang October 13 2010 Page 3 resources within such waters, but not to the waters themselves.10 Finally, the high seas are free for navigation, fishing and other forms of exploitation.11 The Western concept of land, sea, and …

Williamson Chang's pdf for Mauna Kea Testimony and Ret ...

Williamson Chang | the umiverse

50th State Fraud - A Visit With Williamson Chang - YouTube

-

https://www.mcbhawaii.marines.mil/Portals/114/WebDocuments/IEL...Kilikina Kekumano discussed Hawaii‟s legal history with America and questioned the United States‟ claim to the land since the US admits to violating the neutrality of the …

IOLANI - The Royal Hawk: Ten (10) Legal Issues of the ...

Feb 12, 2018 · Ten (10) Legal Issues of the Kingdom of Hawaii that All Civilized Nations Must See, Read, Share - a Review - by Amelia Gora and other Researchers - Williamson Chang (ret. Prof.), Kilikina Kekumano, Francis Boyle (Int'l Atty.), et. als.Focus on Kumu/Teachers: Kilikina Kekumano - The Royal Hawk

Hawaiian Kingdom: Important Historical Events - Keep for ...

Apr 26, 2018 · Kilikina Kekumano found Queen Liliuokalani's Opposition to Annexation "red ribbon documents" - it is a lien. She maintains that we are Hawaii Ko Pae Aina. 2015 - Misprison of Treason/Treason committed by Nai Aupuni/Na'i Aupuni, et. als. - Kilikina Kekumano.Did anyone ask the Hawaiians? - townhall.com

Kekumano is concerned that the racial preferences and race-based government will create “at least strong animosity between the people who have always lived together…We don’t have specific ...Akaka bill hearing before the U.S. House Judiciary ...

Kilikina Kekumano, a retired flight attendant who has homes in Poka'i Bay and Williamsburg, Va., said she thought a formal 1993 apology to Hawaiians from President Clinton and Congress for the U.S. government's role in the 1893 overthrow might eventually lead …-

https://www.boem.gov/Honolulu-Transcript-Public-MeetingKilikina Kekumano ATTENDEES: Pamela Adam Ina Agcalon Kawika Au Blaine Cacho DeMont R.D. Conner Paul Conry/H.T. Harvey Associates John Corbin Miranda Foley Janice Fukawa Matthew Gonser Rachel Kailianu Todd Kanja Kilikina Kekumano Don Lasser/Qsela Group Luwella K. Leonardi Monica Machado Jeff Merz/AECOM Glenn Metzler Alton Miyasaka

At Meetings Statewide, Hawaiians Unite Against the Akaka ...

SPECIAL EDITION - Wrongful Dethronement of our Queen ...

Jan 16, 2016 · b) Documents of the Annexation Opposition signed by Queen Liliuokalani found by Researcher Kiliwehi Kekumano at the National Archives, Maryland. c) Queen Emma, widow of Alexander Liholiho/Kamehameha IV, deeded her dower/her interest in the Crown Lands to the "Hawaiian Government" in 1864.Legal Notice: Kingdom of Hawaii 2016-1007 - Rents Due ...

Some of the kanaka maoli:

Greg Wongham

Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell

John Ezzo/Kaulahea

Raymond Kamaka

Uncle Kamaka

Danny/Daniel Castro

Herbert Pratt

Glenn Kuhia/Kealoha Kuhea

Andrew Hatchie

Uncle Hatchie

Bobby Harmon and Friends

Helelani Rabago

Peggy Hao

Aunty Dela Cruz

Bobby Ebanez/Robert Ebanez

Routhe Bolomet

Michael Lee

Pilipo Souza

Aaron Ardaiz

Keoni Paaloa Choy

Tom Lenchanko

Tane Inciong

Pono Kealoha

All the Konohiki, Assistant Konohiki - Oahu, and outer Islands

Hank Fergerstrom

Keoki Fukumitsu

The Asam Twins and their cousins

San Tah and Orin

Joyclynn Costa

Deldrene Herron

Pomai Kinney

Many unnamed others includes the Royal Families

Macky Feary

Iz Kamakawiwoole

Malani Bilyeu

Gabby Pahinui

Martin Pahinui

George Helm

Walter Ritte

the descendants/heirs of all the documented defenders listed above

Other nations with ongoing Treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom, etc.

Mahalo and aloha to all.

Research incomplete.

Something smells and I know it's not us, the Royal Families, kanaka maoli, and friends.

We are Not the ones who did wrong.

aloha.

***************

References:

Huli Community Struggles and Ethnic Studies Soli Kihei Niheu

The following is Soli Niheu’s personal account of the history of the University of Hawaiÿi Ethnic Studies Program as part of the young political community from the early 1970s. It focuses especially on the Kanaka Maoli movement. Soli Niheu has been an active member of the indigenous rights and local land struggles since he as a young man returned from school in the continental US in the late 1960s. Also an early advocate for Pacific indigenous alliances, he has been the leading force in the Hawaiÿi contingent of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) since the early 1980s. Aloha mai, My ancestral name is Hanaleiwelokiheiakeaÿeloa Niheu, Jr., of Niÿihau. I went to school in America, in San José in the 1960s, where I was president of the Hawaiian Club. We tried to maintain cultural values and promote nä mea Hawaiÿi, Hawaiian things. There was a black students’ union group, and I made many friendships with people from the Black Panther Party. My political journey began with the Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato etc., and Roman intellectuals, but also with Jesuit thinkers. I thank my philosophy teacher and my European literature teacher for opening my eyes to “democracy.” I learned a lot. Engineering and philosophy were my fields. Culturally speaking, I was not aware of our great Kanaka Maoli political thinkers such as Malo and Kamakau. I was not exposed to them until I came home. But I participated in some of the civil rights marches. I learned from Martin Luther King and, of course, from Gandhi. I was told by Janet Lai that if I believed in what I believed in, I should return home. And I did.

Coming Home At the time I came home there were demonstrations at Bachman Hall, sit-ins [see articles by Witeck and Sharma in this issue]. That was my first exposure to political issues in Hawaiÿi. Linda Delaney was president for the Associated Students of the University of Hawaiÿi (ASUH) at that time. We were protesting the war. When I first came, these guys, Mervyn Chang and Ray Catania, were working with a group and putting out the political paper, Hawaiÿi Free, from a van. Chang approached me and asked if I were an undercover cop. And I looked at him: “Hi brah, you must be nuts!” That began my close friendship with Mervyn Chang. I also met Kehau [Lee]. She went to Cuba. So I approached Kehau and told her, “Gee, you go fight for the Cubans, and no fight for the Hawaiian people.” I guess she just ignored me; she was politically trained by the House people of Tenth Avenue. They had a collective there called “the House.” It was under the leadership of Herb Takahashi. Some of the others there were Pete Thompson, Diane Choy, and Gwen Kim. They had their Marxist study group. The first Kanaka Maoli political struggle I was involved in was protesting a bill introduced in the State Legislature to take over Niÿihau by condemnation and turn it into a park. That struggle was put forward by Pinky Thompson, the administrative aide to John Burns. With my family, I lobbied all the legislators against the bill, speaking on behalf of our ÿohana [extended family] from Niÿihau. As a consequence, the bill was defeated. There was too much opposition. The Robinsons did not take a politically upfront profile; they just stayed in the background, while other people came forward to

2

support them, like we did in the Kanahele and Niheu ÿohana: Iliahi Kanahele, cousin Donald, and his son. That was in 1969.

Kökua Kalama and Ethnic Studies The struggle to stop the eviction of farmers to make way for upper-class housing in Kalama Valley on Oÿahu was closely related with changes in the Ethnic Studies Program. We formed the Kökua Kalama in 1970. The leadership was provided by myself, Larry Kamakawiwoÿole, and Kalani Ohelo, whom I met at the 1970 Youth Conference. Kalani was a young, outstanding, vibrant personality from Pälolo. Ethnic Studies students devised the slogan “Our History, Our Way,” and I can still see Al Abru – a fellow of Portugese descent – carry the sign and shouting. He became a well-known disc-jockey, and like many of the other students, he was also a member of Kökua Kalama. We had them all: Korean, Gwen Kim, Mary Choy, Linton and Dana Park; Japanese, Ko Hayashi and Lucy Witeck; Filipino, Ray Catania and Joy Ibarra, I think; Pake [Chinese], Carl Young; Kanaka Maoli, Roy Santana. Many Känaka Maoli but mixed blood, locals, also participated. On campus at the same time, a struggle went on, in regards to the Ethnic Studies Program. The director of Ethnic Studies was Dennis Ogawa, but because of conflict and in-fighting, eventually the people wanted Larry Kamakawiwoÿole to be the head of the Ethnic Studies Program. When Larry became the alakaÿi [leader] for that struggle, he went out to the community to get support. He gave me a call, and he gave Kalani Ohelo a call, to at least talk story about the Program. At the same time, there were Kehau, Jay Walbenstein, Linton Park, and, I think, John Witeck, who were involved in the Kökua Kalama Committee, as I think it was called at that time. The Hayashis, Ko and Lori, were also involved. They took the initial fights; they got arrested first. Larry Kamakawiwoÿole of Ethnic Studies decided not only to support the Kalama Valley residents, but to take a leading role in that struggle. So we had this thing going on between Kökua Kalama and Ethnic Studies. This activity initiated the renaissance of Hawaiian self-determination and, in a certain respects, sovereignty, because we wanted the military out of Hawaiÿi. We wanted to control immigration; we wanted our lands to go back to our people. We wanted the multinational corporations to get out of Hawaiÿi; we wanted the Bishop Estate to fulfill its fiduciary duties to our people. In one of our meetings with the Bishop Estate, Ed Michaels said that Hawaiian lifestyle should be made illegal. That was a famous quote that we used in our papers. He was the PR man [for the developers] in Kalama Valley. We organized the residents of Kalama and as a result, people like Moose Lui, Mama Lui, George Santos, and the Richards family (Black and Ann) played key roles in the struggle. We also had support from some of the local groups, aside from the House. One, for example, was a group called Concerned Locals for Peace with the family of Nick Goodness. Others were some church groups from Aina Haina and Niu Valley, and, of course, Marion and John Kelly also supported that struggle. Eventually more groups came to support. One group, however – the Hawaiians – was rather hesitant to support us, because whenever the topic of Kalama Valley came up on the TV screen, too many haole [white people] were seen, especially the hippie type, carrying banners and stuff like that. It did not look like a Kanaka Maoli struggle. Some of us sat on the board of directors of the Hawaiians, a group started in July of 1970. It was the first statewide political demonstration by Hawaiians since the days of the Liliÿuokalani protests and the Hawaiian Civic Club in the 1920s, I guess. The Hawaiians were the first group in contemporary times to question the state and its obligations towards our people. They felt that the Hawaiian Homes Commissioners were failing in their fiduciary

3

responsibilities by allowing long-term leases for non-Hawaiians, like the Parker Ranch and countless others. Homestead land was also being used for schools and airports that had nothing to do with providing land for the people with the necessary koko [blood]. The Hawaiians put forward people like Jimmy Sablan and Georgiana Padeken. The group was primarily led by Pai Galdeira, a young fellow from Waimänalo. He was the alakaÿi for that hui [group] and in several meetings with us, he pointed out that they could not support us, because whenever you mentioned Kalama Valley, there were too many haole holding signs. First we decided that only Känaka Maoli could be part of the leadership. Then we changed it to locals. In our public relations, the community groups would only show Känaka Maoli and locals speaking on behalf of the organizations. And by local I mean those peoples who were oppressed by the plantation system, those whose ethnicity was Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, etc. The occupation had off and on four-hundred people, and a lot of support came from the white peace activists and environmentalists. Now the latter were asked to leave to ensure that the flavor was local. I think that was an important move on our part, and I must say that some of the whites understood the reasons and rationale – people like John Kelly and John Witeck, who were quite active, they understood – but some other people did not appreciate being asked to leave and displayed their frustration. In Kökua Kalama’s first beginnings, the primary seeds were Känaka Maoli. People like – besides myself, Kalani and Larry – Pete, Kehau Kaipo Lee, Lora Ellen Castle, and we must not forget, Edwina Akaka. She was also part of our group. A lot of the membership were students in the Ethnic Studies Program. In 1971, we changed the name to Kökua Hawaiÿi. One of the primary reasons for the name change was that we had to have a “global understanding.” In many of our study sessions we read about Mao, Marx, and Lenin, and in order to have Kökua Hawaiÿi be proletarian, we had to change our criteria for leadership. We formed alliances with groups such as the Young Lords Party of New York, and IWK and other Chinese and Japanese groups out of San Francisco. They were oriented towards the teaching of Maoism, Marxism, and Leninism, and many of the teachers were young people like Juan Gonzales of New York. At this time, we also managed to communicate with some of the indigenous people of Alaska, the Inuit. The reparations of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act were important to us, and we had a big conference at the Makiki Christian Church in Honolulu, inviting the Alaskan people to come over here. This was under the leadership of a group from the House collective. Some of the leadership in Kökua Hawaiÿi were House people, trying to come in and influence us with Marxism, Leninism, and all those types of things. However, when the time came for the eviction of the residents of Kalama Valley, a call was put forward by the leadership of the House collective not to participate in the boycott, not to get involved or arrested, but some of the people like Ko Hayashi and Pete and Gwen from the House broke the directive from their leader; they did come up to the Valley. Why they were supposed to stay out of the Valley, only Herb Takahashi, Mel Chang, and those guys would know. The Ethnic Studies Program helped organize the China People’s Friendship Association. There were tours between here and China in the 1970s. One of my degrees is in hotel management and tourism, and when they initiated a fundraiser to send people to China, it was quite clear to me that they were charging too much. Also, if they were going to charge that much for these tours, they should have provided more slots for indigenous peoples. This was a big issue. Some of our people went, though. Kalani Ohelo did go, and Edwin Richards from Hauÿula, who was married to Margaret Richards, who was active in the welfare rights organizing committee back in the seventies. Pete Tagalog went, because the organizers provided scholarships. There was a series of tours. It was important to expose some of our grassroots people to world

4

issues. In China at that time, a lot of things were going on, so we felt the need for people to gain first-hand knowledge. This was political education, to learn from what was happening in China. It was an excellent idea.

Land Struggles and Kökua Hawaiÿi Kökua Hawaiÿi played a very important role, not only in the Ethnic Studies Program, but also in the Kanaka Maoli movement and in local land struggles. We were all over. So many struggles ... I do not see how we did it. All kinds of struggles, from PACE [People Against Chinatown Evictions], to Heÿeia Kea, Waiähole-Waikäne, Nukoliÿi, to Niumalu-Näwiliwili. I would like to recognize some of the leadership in these struggles. In Kalama Valley, people like the pig farmers George Santos and Otelo, Black and Ann Richards, and Moose and Mama Lui were some of the key figures. We were working with Jerry and his wife Rocky in Heÿeia Kea, fighting eviction by Hawaiian Electric. In Chinatown, we worked with Emile Makuakane, Charlie Minor, Duke Choy, May Lee, Oliver Lee, and others. They tried to evict people from one of the buildings there, so a call went out from Emile for Kökua to come on down. So we went down there and supported the evictions. I got arrested, when we tried to stop the eviction by locking arms. As people from outside, we could only do certain things. It is so important that we remember that the leadership in any struggle should be the people who are directly affected. As malihini [outsiders] we should know what our roles are, and not to try to take leadership, which would be wrong, because part of the process of selfdetermination is for people to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development. To prevent centralized bureaucracy is one of the things we must strongly support. Among the Hawaiians, we had people like Georgiana Padeken, who played a very important role. Others were Randy Kalahiki and Christine Teruya from Maui. From the Big Island, we had tons of people, among others Joe Tassell, Dixon Enos, and Boot Matthews. I mention these names to let people know that there were supporters out there who never received appropriate recognition for the sacrifices they made. We originally had a committee in 1972 investigating landing on Kahoÿolawe, but it was not until several years later that the first landing took place. In PKO [the Protect Kahoÿolawe ÿOhana] you had the Helms, the Rittes, and Emmett Aluli, just to mention a few. From Molokaÿi there was also Judy Napoleon. She was with the Hawaiians and with Hui Ala Loa, which was the beginning of Protect Kahoÿolawe ÿOhana. There was a struggle with Molokaÿi Ranch, regarding access to the west coast of Molokaÿi, Kaluakoÿi, and all those places. I went there to support them. Speaking about Molokaÿi struggles, I think that Kökua Hawaiÿi made a big mistake, because of a memo of the steering committee. I initiated a communication, inviting PKO to come to Kökua Hawaiÿi if they needed to get information out. But unfortunately, we did not give enough support to PKO and Hui Ala Loa. We did not print some of their requests in our newsletter, Kökua Hawaiÿi. The collective that was printing the paper decided against providing technical support. They condemned PKO’s material as “cultural nationalistic.” I was so angry. That was a conflict between the cultural and Marxist perspectives, and we were too dogmatic. That is what I think. But then, others might say otherwise ... We must not forget Joy Ahn. She has been in the movement for a long time. She was working for Patsy Mink, and when we first met her, we were quite impressed with her manaÿo [thinking]. One of my obligations as a leader was to try to drag her into Kökua Hawaiÿi. It was just a matter of going, “Hi, Sister, how about coming with us?” Her politics was clear already. It was not hard.

5

Speaking about people working with us, we had Jimmy and Rosanne Ng of Kona, whom I knew up in San José where I went to school with Jimmy. When they came back to Hawaiÿi, I was at the airport sending off our contingent, Kalani Ohelo and Edwina Akaka (commonly known as Moanikeala Akaka), off to the Black Panther Conference in Washington, DC. When I sent them off, here come Jimmy and Rosanne. Straight from there, we went to Kalama Valley. When Kalani and Edwina returned from the conference, they brought the idea of wearing berets, but some of us, me and Mary Choy for instance, refused to wear berets. In the Niumalu-Näwiliwili struggle in 1973, there was Stanford Achi. Here was a man who worked all his life, a hard worker, now threatened by eviction for resort development at Niumalu-Näwiliwili. I think that without Stanford, his wife June Achi, and of course their daughter, Karen, we could not have done it. The sacrifices they made as a family were just tremendous. With some of the students of Ethnic Studies, we went there as a unit, along with the John Kelly crew. John provided technical and organizing support. We won the struggle. In the Waiähole-Waikäne struggle, we worked with Bobby Fernandez, Bernie Lam Ho, Hannah Salas and her husband and their Guamanian contingency. Many Chamorro farmers and residents were involved. They were strong; it was beautiful. And, of course, Ike Manalo and some of the Filipino contingency were key persons. In the Ota Camp struggle, we had Pete Tagalog. We were working with Tom Ebenez in the struggle to prevent eviction of the residents of Hälawa Mauka to allow H2 to go through. The state passed a bill that any time they removed people for a state project, they would have to pay them a certain amount, depending upon the number of members of the household and the number of rooms in their homes. That was the end result of that part of the Hälawa Mauka struggle. At the time, it was an important victory. The Aloha Stadium struggles were even more interesting. The state government was always trying to divide us, and what they did in this case was to send Abraham Akaka [a well-known Kanaka Maoli minister] out to bless the Stadium with his Kamehameha Koa Bowl. But the residents of lower Hälawa, Kupi Palio, Shirley Nahoopii, and the rest of the ÿohana – I can’t remember all the names, but the leaders were women – they confronted Akaka, and he put down his Kamehameha Bowl. He did not use his Kamehameha Bowl to bless the Stadium. Some of the workers got killed. In fact, even a safety inspector was run over by a cement truck. When some of the other workers died in accidents, Akaka suggested to give Kupi Palio a call and ask her to come down. There was a movement called Stop the TH-3, and I remember the slogan was "Stop TH-3, for land and sea" – and that movement stalled the construction for years. The highway did not go through Moanalua Valley as planned; it was shifted to Hälawa Valley. John Dominis Holt supported our struggle, and he also provided financial assistance to many people in the sovereignty movement, including funding a tour to Aotearoa [New Zealand] for indigenous artists. The alliance of John and his wife Patches with the movement was one of the good things that came out of that struggle. We formed this Hawaiian Stop All Evictions Coalition. All the leaders of community associations who were facing evictions, from Waiähole-Waikäne to Ota Camp and Hälawa, a whole bunch of people came down, even from Nukoliÿi. We had a big demonstration, a march to stop the H3 [freeway]. Paige Barber was involved, Tom Ebenez from Hälawa Mauka was a leader, and Kupi Palio and Shirley Nahoopii were from Hälawa Makai, the Stadium. They all came together. I organized the first Apprenticeship Council in the Carpenters’ Union, nationwide. We provided different levels of apprenticeship according to the numbers of years you have been an apprentice. I became the chairman of the council. When the question came up regarding the construction of the H3, the unions got together and had hundreds of workers showing support for H3 at a hearing at the City Hall. I spoke

6

out against it, and that exposed me: how could I talk about being for the workers when here I was fighting against the freeway, a project which would provide jobs for hundreds of workers, carpenters, steel men, electricians, and masons? That was a contradiction as far as my being a union person, fighting for jobs. But I took the position that it was only a short-term solution; as soon as the job was done, they still would not be able to provide homes for our carpenters or people in the union. The people who were really “making out,” when you looked at it, were the multinational corporations ... and they made the workers do the dirty work for them. Perhaps the overhead rail system would have been better, providing more jobs for a longer period of time, less disruption of the traffic flow, and less destruction of the environment. When it really came down to it, I took the position for cultural rights versus workers rights, (proletarian rights). It is a hard choice under the capitalist system. When I did that, there too went my job opportunities as far as my working as a carpenter. I was “black-balled” and started getting all the dirty jobs, the dangerous jobs. Our group was also involved in the Ad hoc Committee for a Hawaiian Trustee, in 1972 and in ALOHA [Aboriginal Lands of Hawaiian Ancestry] led by Louisa Rice and her son, Herbert DeMello, in 1972. Peggy Hao Ross returned home in 1972 and initiated the ÿOhana o Hawaiÿi. There was the Congress of Hawaiian People, in which Paige Barber was one of the leaders, and there was Home Rule with Fred Cachola, Hui Hänai and many others. In the 1980s there was Hui Nä ÿÖiwi. We put on the first sovereignty forum 1985 and fought Waimänalo evictions that same year. In Waimänalo, there were two particular struggles that we participated in. One was the Waimanalo Plantation struggle under the leadership of Herb Takahashi and some of the people that he represented. We worked with Walter Kupau fighting the eviction there, and we preserved housing for the plantation community. We also had the Waimänalo park eviction further down the road. Kalani Ohelo and Kamakea played a strong role there. So all these struggles were actually connected to Ethnic Studies. I got arrested twice from the beach park and then we went and occupied the Hawaiian Homes office, Georgiana’s office, for two or three days. The guy who came to arrest me there with the State Law Enforcement Division was a carpenter whom I knew from the time that I organized the Carpenters’ Apprenticeship Council. He was one of my supporters at that time.

Ethnic Studies and the People’s Committee I did not get involved with Ethnic Studies Program until 1970. Because of the problems with the program director at the time, we decided to support Larry Kamakawiwoÿole as director. It was quite obvious that he had mana [divine power, authority]. He was the type of person who was quiet and very effective. He was very intelligent, and because he was Kanaka Maoli, we went and supported him. We formulated a leadership structure for Ethnic Studies with a People’s Committee in order to get input from different perspectives. It had representatives from the faculty and student groups as well as from the community. It worked out pretty well, as a total effort. We showed a united front. In the People’s Committee, we had a faculty contingent, of five people, the community contingent of five people, and the students. Some of the names of Ethnic Studies faculty were Kay Brundage, Ross McCloud, Pua Anthony, Marion Kelly, and Agnes Nakahawa-Howard. Representing the community were myself, Francis Kaÿuhane, Roy Santana, Mary Choy, and I think the last one was Buddy Ako. Francis was with the group called the Hawaiians; Roy Santana, Mary Choy and I were with Kökua Hawaiÿi; and Buddy Ako was with the Youth Center in Hauÿula. Some of the students I remember were Terri Kekoÿolani, Davianna McGregor, Guy Fujimura, and Mel Chang, and Pete Thompson.

7

Before we were officially recognized as a program in the College of Social Sciences under Dean Contois, the dean set up the Steve Boggs Committee to investigate the possibility of a permanent Ethnic Studies program. They had to have a separate group of faculty determine the validity of Ethnic Studies. Representing the administration were Dean Contois and Chancellor Takasaki. We had to convince the Board of Regents to support the program, and we succeeded because of persistence and because of the importance of the Ethnic Studies Program. At that time at the University, this was the only opportunity to learn the history from a native or from a people’s point of view. There was no Center for Hawaiian Studies. In fact, one of the things that came out of the Ethnic Studies Program was an understanding of the necessity for Hawaiian Studies. This University can have a Korean Studies Center, all kinds of studies and programs – and the University sits on ceded lands – so why was there no Hawaiian Studies? Hawaiian was taught as a foreign language. Now we have both Hawaiian Studies and Ethnic Studies.

Independence and Self-Determination Self-determination is the will of the people, but sometimes people are misinformed because of slick propaganda or false media coverage. Based upon this misinformation, they take positions that are contrary to the best interests of all people. One of my good friends in the Mormon church says that if a majority of people express delight for a certain thing, it does not mean that it is right. Using the example of cow dung, he said that even if it attracts a lot of flies, it does not mean that cow dung is good. What he was really saying was that just because a majority expresses a certain desire, like continuing the wardship of the United States (which at the present time, the polls indicate that the majority of people want to continue), this does not mean that this is the right way to go. I think that it is beginning to change, however. At the present time, it is getting fairly close to the fifty percent mark. That is why education is so important. Self-determination is a catchword, and it is a positive word. But you have to be very careful. If people are not afforded the truth, the real history, they will voice the continuance of welfare from the colonizers. There is a difference between selfdetermination and independence. Self-determination is a cop-out for our case, particularly because we are colonized. Part of decolonization is that we have to decolonize our minds. People who are not part of the processes of decolonization will end up in a worse position. So, when you talk about the native Hawaiian vote [in 1996] and a constitutional convention proposed by Hä Hawaiÿi [in 1998], it is kind of spooky.

Nuclear Free – and Independent – Pacific We have played a very important role in the movement for self-determination and sovereignty in association with the Nuclear Free Pacific movement. In 1974, or it might be 1975, there was conference in Suva, Fiji, for a Nuclear Free Pacific. The people who went there from Hawaiÿi were Pete Thompson, John Kelly, Auntie Peggy Hao Ross, and her husband. Auntie Peggy’s husband was involved in the bombing of Bikini Island, and he got cancer from participating in that testing. The second conference was in Pohnpei, I think, and the third one was in Hawaiÿi in 1980. At that time, it was called the Nuclear Free Pacific (NFP). The organizers down here were mostly peace activists. I got involved as the head cook; that was my beginning. One of the things that were upsetting was that the organizers were only allowing three delegates to represent Hawaiÿi. I took the position that because this was a once-in-a-lifetime thing, the fact that our people got a chance to

8

be with people from all over the world to protest the nuclear build-up, and therefore, we should have more delegates. Bernard Punikaÿia felt as strongly as I did that we needed more positions opened for Kanaka Maoli activists, and we met with the organizers on the steering committee at the American Friends Service Committee. We took a strong position, Bernard and I. Not all Känaka Maoli felt that it was appropriate to take a certain line. But we insisted and finally said, “Look, if you don’t give us more delegates, we are going to boycott this whole conference.” I think they got the message. So they asked us, “How many delegates do you want?” “Oh, a dozen.” What happened was that the organizing committee met separately to decide our request, and they were quite concerned, but Bernard and I stood fast. They came back with a counter-offer, a compromise. Politics, as defined by certain people, is the art of compromise. “How about five delegates?” Bernard and I left the room and went outside to discuss the counter-offer, which we accepted kind of in a laughing way, because we exerted self-determination. We went back inside and told them that we accepted. But then they wanted five names, specific names. We told them, “No, we want five slots so we can allow people to rotate and be part of the delegation.” We wanted people from the neighbor islands, people like Joyce Kainoa, Emmett Aluli, and Judy Napoleon to get a chance to participate. Then we had Angel Pilago and Edwina Akaka, and people like Hoÿoipo DeCambra who was not a delegate, but helped with the cooking. What happened at that conference was very, very important. We called for the indigenous peoples to caucus – to use a haole word – among ourselves. Those people who spoke at that meeting strongly believed that we should include independence as part of the movement in the Pacific. That was where people like Hilda HalkyardHarawira, with the Maori People’s Liberation Movement, and Liz Martin, with a group called Te Matariki, expressed strong feelings of including independence in a change of the name. The supporters for this change were primarily Känaka Maoli, Maori, and Maohi (Tahitians) – those peoples who were involved in independence struggles. We also got support from the different island states’ representatives, and of course from the Aboriginals of Australia. There were about half-half white people and indigenous people. After the caucus, we took the position to expand the name from NFP to NFIP. Some of the peace activists were kind of upset; they felt that they were “hijacked” (that was the exact word that they used) by some of the indigenous activists, such as myself. They knew they would look bad if they did not support us. A lot of the times when we have struggles, the involvement of environmentalists and peace activists is a dead end for our people, because once their goals have been accomplished, they no longer support our indigenous struggles. They really don’t, especially the Greenpeace people here in Hawaiÿi. Even some of the parts of the peace movement in Aotearoa call for nuclear free provisions, but when it comes to supporting Tino Rangatiratanga [sovereignty] for the Maori, they just slide into the background. We have support from some of the peace activists, though. We have good people like Bill Armstrong and others. Even within the black struggles, they are pushing for black rights, but when it comes to supporting Pacific rights, it becomes very difficult for them. Other ethnic groups also compromise. They get what they want, and just compromise our rights – that is one of the main problems, even to today. Our first main office of NFIP was here in Hawaiÿi. Then it moved to Aotearoa, and from there it moved back to Fiji. We do have an office in Sydney, but that office is primarily for the newsletter, Pacific News Bulletin. We were in limbo for a couple of years. There were complications between the head of the office who was a haole and some of the staff; the two could not get along, because the director offended the indigenous core group. We furthermore needed to share the responsibility with the rest of the Pacific, so we decided to move it to Aotearoa.

9

I have always been part of the independence movement, so in 1981 I did a threemonth tour of the Pacific. One month in Aotearoa, one month in Australia, and one month in Tahiti. We got to meet a lot of people and created bonds that lasted for many, many years. In fact, the bonds have become very strong, even to the point where I became the Godfather of Hilda’s daughter, whose Kanaka Maoli name is Aloha ÿÄina. She was named after the association with Protect Kahoÿolawe ÿOhana. Emmett Aluli is the Godfather of one of Hilda’s other daughters. So we have been politically and personally allying with the Maori movement. They call it Whanau, hänau [to give birth]. The “f” is our “h,” but they spell their “f” with a “wh.” To this day, there are very close political and ÿohana type relationships between our peoples. This is the same way our people built alliances in the old days. In the art of politics, in order to prevent bloodshed, you offer women to be part of the other side, thus creating alliances. Kamehameha, for example, married a high-ranking chiefly woman to increase his mana and to make alliances with other groups. I am still the alakaÿi of NFIP Hawaiÿi, and my whole family has been very helpful. Kalama Niheu, one of my daughters, especially, is very active in the Pacific context. I was shocked when Kalama decided to become part of the struggle. We did not push her; we did not lecture her. She came upon it herself, she exercised her on selfdetermination. Her name carries ancestral obligations. Kalama was named after our participation in Kalama valley, but culturally, the valley’s name, according to Mama Lui, was Wäwämalu. Bishop Estate, the developers, changed the name.

Ka Päkaukau In the late 1980s we did a lot of our work through Ka Päkaukau, the round-table, which had only Kanaka Maoli members. The original organization was the Pä Kaukau coalition. In Pä Kaukau, we had Nä ÿÖiwi o Hawaiÿi and ÿUhane Noa (Nihipali them). We also had Peggy Hao Ross, Steve Maldonado, Uncle Tom Maunupau, Kawaipuna Prejean, Puhipau, ÿÏmaikalani Kalahele, and of course myself. That was Pä Kaukau. Our efforts in Ka Päkaukau were always to support the front-line struggles, and to provide them with information that would support the sovereignty and independence movement. We aimed to support the cultural rights and the right to exist in harmony with ourselves and our culture and with our people. And that is the role we have always taken, to make sure that people get informed as much as possible - to be aware that we are not isolated, that we can work together on a community by community basis, and that we do not need centralization of power. It is better to be community-based so that we can actually control our leaders and prevent them from going off on a tangent and start selling away our rights. In movements that have only one leader, that is often the beginning of the end. Even with Kamehameha, the centralized power contributed to the destruction of our people to a certain extent. Look at the Bishop Estate now. We have Bernice Pauahi Bishop, who was a direct descendent of Kamehameha. Then she develops an institution now worth about fifteen to twenty billion dollars, a trust over which five trustees have control. You do not have to be a rocket scientist to know that they are not doing their fiduciary duty. That has to be pointed out. What is happening at Bishop Estate with members of a trust, the same thing happened in Aotearoa where trust boards totally sell out the rights of their ÿiwi, their tribes. We have to be very careful with statewide associations, for example, the Hawaiian Civic Clubs, and even the State Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations, SCHHA. We have to be very careful. Imagine, we have an institution that has a portfolio of over fifteen billion – they have more money than many countries. And they are responsible for the welfare of so many thousands of Kanaka Maoli beneficiaries. We know that they can do a better job! They have many good teachers up there, like Randy Fong, who has done an excellent job in educating not only young

10

people through song and dance, but a lot of other people out there. They did a great Höÿike [show] on the overthrow.

The Responsibility of the University Students and Faculty Today It was good that the Ethnic Studies Program went the way it did. It was good, considering all the activities we participated in with the community struggles. It is very important to maintain contact with the community, and somehow I do not see that happening now. I may be wrong, but in all the major struggles in recent times that I have participated in, I have not seen a strong support from Ethnic Studies. The intent of the Ethnic Studies Program was to account for the true history of our peoples, whether it be Känaka Maoli, or others. It is always important to maintain the right connections and get information from first-hand experience, and not to be isolated on the campus. Now I see a lot of the community contact happen with the Center for Hawaiian Studies students. They are out there, a lot of their students are involved in community struggles, involved in Ka Lähui and very active on campus too. The more exposure our struggles get, the more the movement for sovereignty and self-determination will move forward. However, it is most unfortunate that some members of our Kanaka Maoli intelligentsia cannot get along. We have some taking different positions. The differences among the leaders do affect the community, and we do not have enough time in our struggles with our “masters” to waste expertise. I would like to recognize Marion Kelly as part of the Ethnic Studies Department, as well as part of local land struggles, for the effort she makes in all the things she researches and writes of our fantastic culture and the beauty of our people. A lot of things that she writes provides important information as to our way of life. I also honor her for her long involvement in our movement, in the peace movement, and in the human rights movement. I appreciate her expression of support for our struggle, but also her criticisms – of which we had many. They make me stop and think, just like the phrase, “The dream of a slave is not freedom, but a slave of its own,” which has proven true so often in liberation struggles in Africa and in South America, and can happen here in our struggles at home as well as struggles elsewhere in the Pacific. I would like to stress that there is no one person, no one group, who will determine the political and economic direction of our peoples, and that it is the responsibility and obligation of all groups or individuals to fully understand their or his responsibilities and obligation to our people in order to move forward. We have to know when to give and when to take, and we must be in contact with our peoples out in the communities as much as possible in a day-to-day existence. We must always support those groups that are kü’ë, resisting. We can have all those conferences, we can have all these demonstrations, but without working with our people on a day-to-day basis, it becomes difficult to reach the goal of obtaining independence or exercise selfdetermination in my lifetime. This is my manaÿo; some people might agree, and some might disagree. Every opportunity should be afforded to those people who disagree with what I have said to state their opinion. In retrospect, the word mana comes into my mind, whether it applies to individuals, organizations or ÿohana. Your mana depends on your ability to influence people to move in the direction of self-determination. Part of the responsibilities of mana is that you would have to give your mana to others, so whatever work that you have done in the past – in moving the people in a direction of self-determination – must continue forever and ever. For what you have done in the past – and that and a buck won’t buy you a cup of coffee – its rhetoric can provide a common cause only for so long. That is why we say in Ka Päkaukau: “Educate, ed-your-cate, edu-my-cate, kükäkükä [discuss], hele wäwae ka ÿolelo (walk the talk) and küÿë (resist).” This is an off

11

shoot of Kökua Hawaiÿi’s principle of huli. What we said in the past was that huli means to discover the truth in which to overturn, in which to make things pono {in balance, righteous], in building a new society based upon our indigenous values. Huli means find the truth, but huli also means overturn, and huli is a new kalo generation that propagates new plants. Excerpts from interview for Social Process in Hawaiÿi by Ulla Hasager, March 1998

Reference: http://www2.hawaii.edu/~aoude/ES350/SPIH_vol39/08Niheu.pdf

**********

facebook:

* Pirate Eyes on Hawaii Series: Identity Thieves, Pirates, Pillagers, Squatters, Justice Failures Injuring Our People...…

No comments:

Post a Comment