Abraham Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln.

CHAPTER XXIV

Abraham Lincoln

the

Liberator of the

Slaves

Abraham Lincoln

the

Liberator of the

Slaves

[1809-1865]

The Southern slaveholders hoped by this war to gain from their weak neighbor territory favorable for the extension of slavery. For slavery had long since been dying out in the States east of the Mississippi and north of the Mason and Dixon Line and the Ohio. On the south of this natural boundary line the soil and climate were adapted to the cultivation of rice, cotton, sugar, and tobacco. These four staples of the South called for large plantations and an abundance of cheap labor always subject to the bidding of the[Pg 283] planter. Slavery satisfied these conditions, and therefore slavery seemed necessary to the prosperity of the South.

It was because the soil and climate north of this natural boundary line did not favor the use of slaves that slavery gradually died out in the North. The result was that in one section of the Union, the South, there was a pressing demand for slavery; and in the other, the North, there was none. As time wore on, it became evident that the North was growing in population, wealth, and political influence much faster than the South. Observing this momentous fact, the slaveholders feared that in the course of years Congress might pass laws unfriendly to slavery. Hence, their stubborn purpose to struggle for the extension of slavery as far as possible into the territory west of the Mississippi.

Lincoln's Birthplace.

Lincoln's Birthplace. When Abe was seven years old the family moved to Indiana, and settled about fifteen miles north of the Ohio River. The journey to their new home was very tedious and lonely, for they had in some places to cut a roadway through the forest.

Having arrived safely in November, all set vigorously to work to provide a shelter against the winter. Young Abe was healthy, rugged, and active, and from early morning till late evening he worked with his father, chopping trees and cutting poles and boughs for their "camp." This "camp" was a mere shed, only fourteen feet square, and open on one side. It was built of poles lying upon one another, and had a thatched roof of boughs and leaves. As there was no chimney, there could be no fire within the enclosure, and it was necessary to keep one burning all the time just in front of the open side.

In this rough abode the furniture was of the scantiest and rudest sort, very much like what we have already observed in Boone's cabin. For chairs there were the same kind of three-legged stools, made by smoothing the flat side of a split log, and putting sticks into auger-holes underneath. The tables were of the same simple fashion, except that they stood on four legs instead of three.

The crude bedsteads in the corners of the cabin[Pg 285] were made by sticking poles in between the logs at right angles to the wall, the outside corner where the logs met being supported by a crotched stick driven into the ground. Upon this framework, shucks and leaves were heaped for bedding, and over all were thrown the skins of wild animals for a covering. Pegs driven into the wall served as a stairway to the loft, where there was another bed of leaves. Here little Abe slept.

In the space in front of the open side of the cabin, hanging over the fire, was a large iron pot, in which the rude cooking was done. These backwoods people knew nothing of dainty cookery, but they brought keen appetites to their coarse fare. The principal vegetable was the ordinary white potato, and the usual form of bread was "corn-dodgers," made of meal and roasted in the ashes. Wheat was so scarce that flour bread was reserved for Sunday mornings. But generally there was an abundance of game, such as deer, bears, and wild turkeys, many kinds of fish from the streams close by, and in summer wild fruits from the woods.

During this first winter in the wild woods of Indiana little Abe must have lived a lonely life. But it was a very busy one. There was much to do in building the cabin which was to take the place of the "camp," and in cutting down trees and making a clearing for the corn-planting of the coming spring. Besides, Abe helped to supply the table with food, for he had already learned to use the rifle, and to hunt and trap animals. These occupations took him into the woods, and we[Pg 286] must believe, therefore, in spite of all the hardships of his wilderness life, that he spent many happy hours.

If we could see him as he started off with his gun, or as he chopped wood for the fires, we should doubtless find his dress somewhat peculiar. He was a tall, slim, awkward boy, with very long legs and arms. In winter he wore moccasins, trousers, and shirt of deerskin, and a cap of coonskin with the tail of the animal hanging down behind so as to serve both as ornament and convenience in handling the cap. On a cold winter day, such a furry costume might look very comfortable if close-fitting, but we are told that Abe's deerskin trousers, after getting wet, shrunk so much that they became several inches too short for his long, lean legs. As for stockings, he tells us he never wore them until he was "a young man grown."

But although this costume seems to us singular, it did not appear so to his neighbors and friends, for they were used to seeing boys dressed in that manner. The frontiersmen were obliged to devise many contrivances to supply their lack of manufactured things. For instance, they all used thorns for pins, bits of stone for buttons, and home-made soap and tallow-dipped candles. Candles, indeed, were a luxury much of the time, and in Abe's boyhood, he was obliged in the long winter evenings to read by the light of the wood fire blazing in the rude fireplace of the log cabin.

[Pg 287]

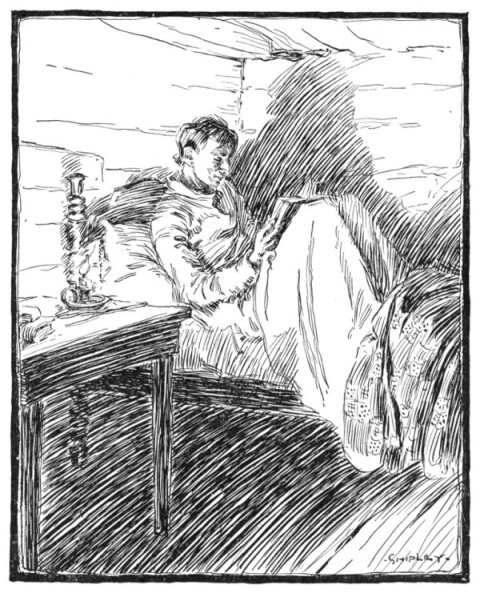

Lincoln Studying.

Lincoln Studying. A year after this sad event, his father brought home a second wife, who became a devoted friend to the motherless boy. Energetic, thrifty, and intelligent, this woman, who had been accustomed to better things than she found in her new home, insisted that the log cabin should be supplied with a door, a floor, and windows, and she at once began to make the children "look a little more human."

Abraham Lincoln's schooling was brief—not more than a year in all. Such schools as he attended were nothing like the graded schools of to-day. The buildings were rough log cabins with the earth for floor and oiled paper for windows. Desks were unknown, the little school-house being furnished with rude benches made of split logs, after the manner of the stools and tables in the Lincoln home. The teachers were ignorant men, who taught the children a little spelling, reading, writing, and ciphering. While attending the last school, Abe had to go daily a distance of four and a half miles from his home.

In spite of this meagre schooling, however, the boy, by his self-reliance, resolute purpose, and good reading habits, acquired the very best sort of training for his future life. He had but few books at his home, and found it impossible in that wild country to find many[Pg 289] in any other homes. Among those which he read over and over again, while a boy, were the Bible, "Æsop's Fables," "Robinson Crusoe," "Pilgrim's Progress," a History of the United States, and "Weems's Life of Washington."

His step-mother said of him: "He read everything he could lay his hands on, and when he came across a passage that struck him, he would write it down on boards, if he had no paper, and keep it before him until he could get paper. Then he would copy it, look at it, commit it to memory and repeat it."

His step-brother said: "When Abe and I returned to the house from work, he would go to the cupboard, snatch a piece of corn-bread, take down a book, sit down, cock his legs up as high as his head, and read." When night came he would find a seat in the corner by the fireside, or stretch out at length on the floor, and write or work sums in arithmetic on a wooden shovel, using a charred stick for a pencil or pen. When he had covered the shovel, he would shave off the surface and begin over again.

Having borrowed a copy of the "Life of Washington" on one occasion, he took it to bed with him in the loft and read until his candle gave out. Then before going to sleep, he tucked the book into a crevice of the logs in order that he might have it at hand as soon as daylight would permit him to read the next morning. But during the night a storm came up, and the rain beat in upon the book, wetting it through and through. With heavy heart Lincoln took it back to its owner,[Pg 290] who told him that it should be his if he would work three days to pay for it. Eagerly agreeing to do this, the boy carried his new possession home in triumph. This book had a marked influence over his future.

Until he was twenty his father hired him out to all sorts of work, at which he sometimes earned $6 a month and sometimes thirty-one cents a day. Just before he came of age his family, with all their possessions packed in a cart drawn by four oxen, moved again toward the West. For two weeks they travelled across the country into Illinois, and finally made a new home on the banks of the Sangamon River, a stream flowing into the Ohio. The tiresome journey was made in the month of March along muddy roads and over swollen streams, young Lincoln driving the oxen.

On reaching the end of the journey, Abraham helped his father to build a hut and to clear and fence ten acres of land for planting. Shortly after this work was done he bargained with a neighbor, Mrs. Nancy Miller, to split 400 rails for every yard of brown jeans needed to make him a pair of trousers. As Lincoln was tall, three and one-half yards were needed, and he had to split 1,400 fence rails—a large amount of work for a pair of trousers.

From time to time he had watched the boats carrying freight up and down the river, and had wondered where the vessels were going. Eager to know by experience the life of which he had dreamed, he determined to become a boatman. He was hungry for knowledge, and with the same earnestness and energy[Pg 291] with which he had absorbed the great thoughts of his books, he now applied himself to learn the commerce of the river and the life along its banks. When an opportunity presented, he found employment on a flat boat that carried corn, hogs, hay, and other farm produce down to New Orleans. On one of his trips he chanced to attend a slave auction. Looking on while one slave after another was knocked down to the highest bidder, his indignation grew until at length he cried out, "Boys, let's get away from this; if I ever get a chance to hit that thing" (meaning slavery), "I'll hit it hard." Little did he think then what a blow he would strike some thirty years later.

Tiring at length of his long journeys to New Orleans, he became clerk in a village store at New Salem. Many stories are told of Lincoln's honesty as displayed in his dealings with the people in this village store. It is said that on one occasion a woman in making change overpaid him the trifling sum of six cents. When Lincoln found out the mistake he walked three miles and back that night to give the woman her money.

He was now six feet four inches tall, a giant in strength, and a skilful wrestler. Much against his will—for he had no love of fighting—he became the hero of a wrestling match with a youth named Armstrong, who was the leader of the rough young fellows of the place. Lincoln defeated Armstrong, and by his manliness won the life-long friendship of his opponent.

At times throughout his life he was subject to deep[Pg 292] depression, which made his face unspeakably sad. But as a rule he was cheerful and merry, and on account of his good stories was in great demand in social gatherings and at the cross-roads grocery stores. At such times, when the social glass passed around, he always declined it, never indulging in strong liquor of any kind, nor in tobacco.

Lincoln was as kind as he was good-natured. His step-mother said of him: "I can say, what scarcely one mother in a thousand can say, he never gave me a cross word or look, and never refused in fact or appearance to do anything I asked him." He was tender-hearted too, as the following incident shows:

Riding along the road one day with a company of men, Lincoln was missed by his companions. One of them, going to look for him, found that Lincoln had stopped to replace two young birds that had been blown out of their nest. He could not ride on in any peace of mind until he had restored these little ones to their home in the tree-branches.

In less than a year the closing of the village store in which Lincoln was clerk left him without employment. He therefore enlisted as a volunteer for the Black Hawk War, which had broken out about this time, and went as captain of his company. On returning from this expedition, he opened a grocery store as part owner, but in this undertaking he soon failed. Perhaps the reason for his failure was that his interest was centred in other things, for about this time he began to study law.[Pg 293]

For a while after closing his store he served the Government as postmaster in New Salem, where the mail was so scanty that he could carry it in his hat and distribute it to the owners as he happened to meet them.

He next tried surveying, his surveyor's chain, according to report, being a trailing grapevine. Throughout all these years Lincoln was apparently drifting almost aimlessly from one occupation to another. But whatever he was doing his interest in public affairs and his popularity were steadily increasing. In 1834 he sought and secured an election to the State Legislature. It is said that he tramped a distance of a hundred miles with a pack on his back when he went to the State Capitol to enter upon his duties as law-maker.

About four years after beginning to study law, he was admitted to the bar and established himself at Springfield, Ill. From an early age he had been fond of making stump speeches, and now he turned what had been a pleasant diversion to practical advantage in the progress of his political life. In due time he was elected to Congress, where his interest in various public questions, especially that of slavery, became much quickened.

On this question his clear head and warm heart united in forming strong convictions that had great weight with the people. He continued to grow in political favor, and in 1858 received the nomination of the Republican party for the United States Senate. Stephen A. Douglas was the Democratic nominee.[Pg 294] Douglas was known as the "Little Giant," on account of his short stature and great power as an orator.

The debates between the political rivals challenged the admiration of the whole country. Lincoln argued with great power against the spread of slavery into the new States. Although unsuccessful in securing a seat in the Senate, he won a recognition from his countrymen that led to his election as President two years later. In 1860 the Republican National Convention, which met at Chicago, nominated "Honest Old Abe, the Railsplitter," as its candidate for President, and elected him in the same autumn.

The burning political question before the people at this time, as for many years before, related to the extension of slavery into the Territories. The South was eager to have more States come into the Union as slave States, while the North wished that slavery should be confined to the States where it already existed.

Before the purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803, Mason and Dixon Line and the Ohio River formed the dividing line between the free States on the north and the slave States on the south. But after that purchase there was a prolonged struggle to determine whether the new territory should be slave or free.

It was thought that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 would forever settle the trouble, but such was not the case. It broke out again, as bitter as ever, about the Mexican Cession, which became ours as a result of the Mexican War. Again it was hoped that[Pg 295] the Compromise of 1850 would bring an end to the struggle. But even after this second compromise, the agitation over slavery continued to become more and more bitter until Mr. Lincoln's election, when some of the Southern States threatened to secede, that is, withdraw from the Union. These States claimed the right to decide for themselves whether or not they should remain in the Union. On the other hand, the North declared that no State could secede from the Union without the consent of the other States.

Before Lincoln was inaugurated, seven of the Southern States had seceded. The excitement was everywhere intense. Many people felt that a man of larger experience than Lincoln should now be at the head of the Government. They doubted the ability of this plain man of the people, this awkward backwoodsman, to lead the destinies of the nation in these hours when delicate and intricate diplomacy was needed. But, little as they knew it, he was well fitted for the work that lay before him.

While on his way to Washington for inauguration, his friends learned of a plot to assassinate him when he should pass through Baltimore. To save him from violence, therefore, they prevailed upon him to change his route and make the last part of his journey in secret.

In a few weeks the Civil War had begun. We cannot here pause for full accounts of all Lincoln's trials and difficulties during this fearful struggle that began in 1861 and ended in 1865. His burdens were almost[Pg 296] overwhelming, but, like Washington, he believed that "right makes might" and must prevail.

When he became President he declared that the Constitution gave him no power to interfere with slavery in the States where it existed. But as the war continued, he became certain that the slaves, by remaining on the plantations and producing food for the Southern soldiers, were a great aid to the Southern cause, and thus threatened the Union. He therefore determined, as commander-in-chief of the Union armies, to set the slaves free in all territory whose people were fighting against the Union. He took this step as a military necessity.

The famous state paper, in which Lincoln declared that the slaves were free in all the territory of the seceded States whose people were waging war against the Union, was called the Emancipation Proclamation. This he issued on January 1, 1863, and thus made good his word, "If ever I get a chance to strike that thing" (meaning slavery), "I'll strike it hard."

[Pg 297]

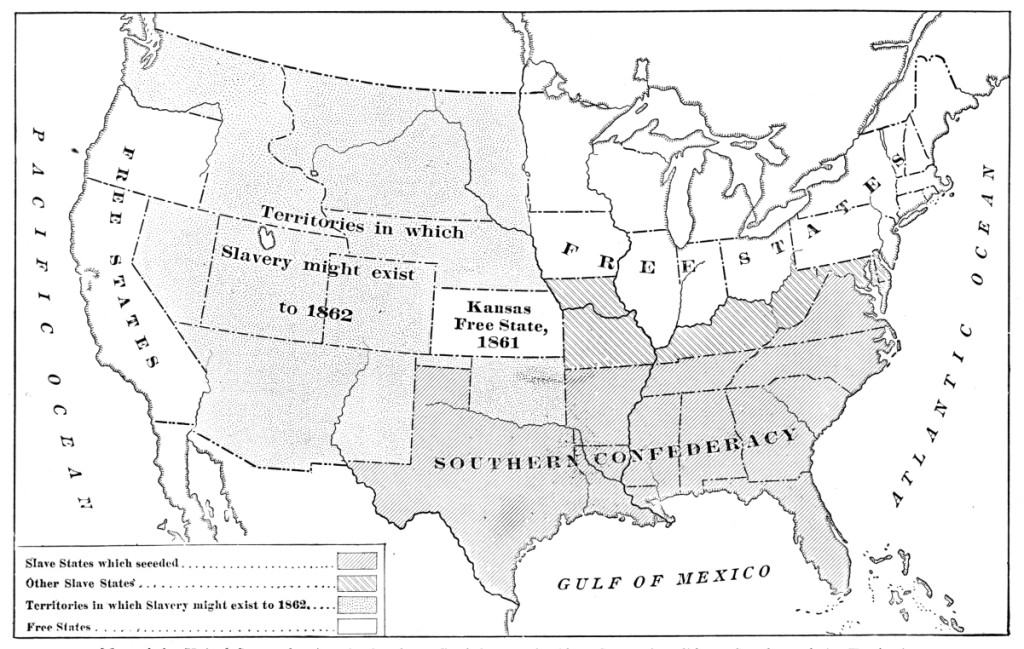

Map of the United States showing the Southern Confederacy, the Slave States that did not Secede, and the Territories.

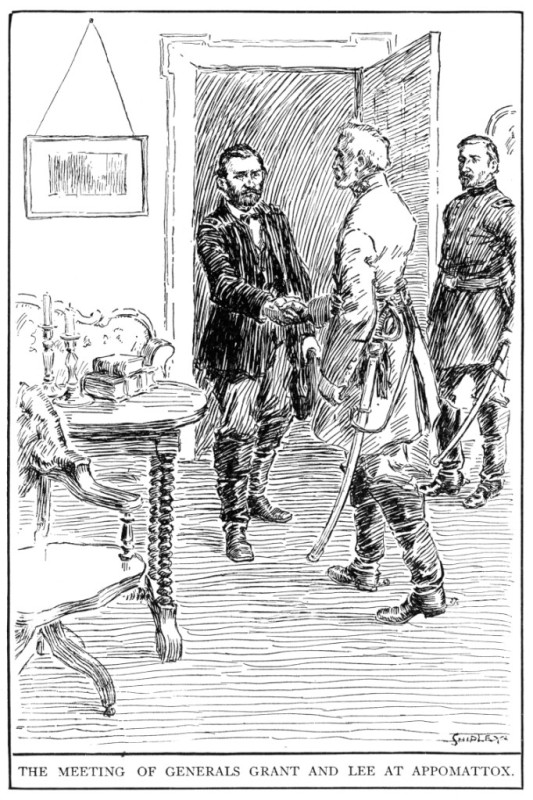

Map of the United States showing the Southern Confederacy, the Slave States that did not Secede, and the Territories. On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered his army to General Grant at Appomattox Court House. By this act the war came to a close. Great was the rejoicing everywhere. But suddenly the universal joy was changed into universal sorrow. Five days after Lee's surrender Lincoln went with his wife and some friends to see a play at Ford's Theatre in Washington. In the midst of the play, a half-crazed actor, who was familiar with the theatre, entered the President's box, shot him in the back of the head, jumped to the stage, and, shouting "Sic semper tyrannis!" (So be it always to tyrants), rushed through the wing to the street. There he mounted a horse in waiting for him, and escaped, but was promptly hunted down and killed in a barn where he lay in hiding. The martyr-President lingered some hours, tenderly watched by his family and a few friends. When on the following morning he breathed his last, Secretary Stanton said with truth, "Now he belongs to the ages." A noble life had passed from the field of action; and the people deeply mourned the loss of him who had wisely and bravely led them through four years of heavy trial and anxiety.

Wise and brave as the leadership of Abraham Lincoln was, however, the drain of the Civil War upon the nation's strength was well-nigh overwhelming. Nearly 600,000 men lost their lives in this murderous struggle, and the loss in wealth was not far short of $8,000,000,000.

But the war was not without its good results also. One of these, embodied later in the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, set free forever all the slaves in the Union; and another swept away for all time the evils of State rights, nullification, and secession. Webster's idea that the Union was supreme over the States had now become a fact which could never again be a subject of dispute. The Union was "one and inseparable."

[Pg 299]

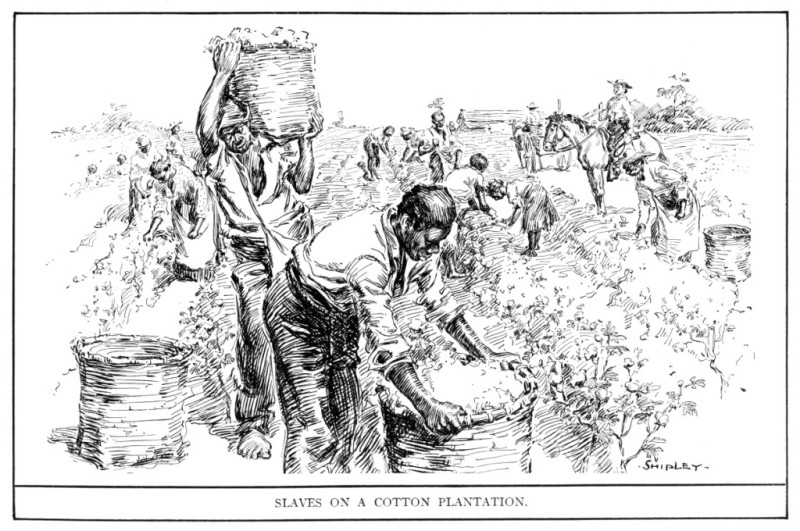

SLAVES ON A COTTON PLANTATION.

SLAVES ON A COTTON PLANTATION. The immortal words that Lincoln uttered as part of his Second Inaugural are worthy of notice, for in their sympathy, tenderness, and beautiful simplicity they reveal the heart of him who spoke them. This inaugural address was delivered in Washington on March 4, 1865, only about six weeks before Lincoln's assassination. It closed with these words:

"With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

REVIEW OUTLINE

The Mexican war.Conflict over the extension of slavery.

Abraham Lincoln in his Kentucky home.

The Lincoln family moves to Indiana.

The furniture and the food of the backwoods people.

Little Abe's busy life.

His personal appearance.

Backwoods makeshifts.

His school life; his reading habits.

Abraham Lincoln as a boatman.

"Honest Abe."

His physical strength.

His kindness and sympathy.

He is elected to the state legislature.

The great debate with Stephen A. Douglas.

Abraham Lincoln as president.

He issues the emancipation proclamation.

His assassination.

[Pg 301]

TO THE PUPIL

1. Explain the conflict between the North and the South over the extension of slavery.2. Form mental pictures of the following: the "camp"; the furniture and the food of the backwoods people; and Abraham Lincoln's personal appearance.

3. What were his reading habits?

4. Imagine yourself with Lincoln when he saw the slave auction in New Orleans, and tell what you see.

5. Tell, in your own words, what you have learned of his honesty, sympathy, and kindness.

6. The greatest act of Abraham Lincoln's life was the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation. What was this?

7. What do you admire in the character of Abraham Lincoln?

Ulysses S. Grant.

Ulysses S. Grant.

CHAPTER XXV

Ulysses

Simpson Grant

and the

Civil War

Ulysses

Simpson Grant

and the

Civil War

[1822-1885]

He was born in a humble dwelling at Point Pleasant, O., in April, 1822. The year following his birth the family removed to Georgetown, O., where they lived many years.

The father of Ulysses was a farmer and manu[Pg 303]facturer of leather. The boy did not like the leather business, but was fond of the various kinds of farm work. When only seven years old he hauled all the wood which was needed in the home and at the leather factory, from a forest, a mile from the village. As he was too small to load and unload the wood, the men did that for him.

From the age of eleven to seventeen, according to his own story as told in his "Personal Memoirs," he ploughed the soil, cultivated the growing corn and potatoes, sawed fire-wood for his father's store, and did any other work that would naturally fall to the lot of a farmer's boy. He had his recreations, also, including fishing, swimming in the creek not far from his home, skating in winter, and driving about the country winter and summer.

Young Grant liked horses, and early became a skilful rider. Lincoln told a story of him which indicates not only his expert horsemanship, but his "bull-dog grit" as well. One day when he was at a circus the manager offered a silver dollar to anybody who could ride a certain mule around the ring. Several persons, one after another, mounted the animal only to be thrown over its head. Young Ulysses was among those who offered to ride, but like the others he was unsuccessful. Then pulling off his coat, he got on the animal again. Putting his legs firmly around the mule's body, and seizing him by the tail, Ulysses rode triumphantly around the ring, amid the cheers of the expectant crowd.[Pg 304]

Although he cared little for study, his father wished to give him all the advantages of a good education, and secured for him an appointment at West Point. This was indeed a rare opportunity for thorough training in scholarship, but Ulysses was rather indifferent to it. He had a special aptitude for mathematics, and became an expert horseman, but with these exceptions, he took little interest in the training received at this famous military school, his rank being only twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine.

After graduation he wished to leave the army and become an instructor in mathematics at West Point. But as the Mexican War broke out about that time he entered active service. Soon he gave striking evidence of that fearless bravery for which he was to become so noted on the battle-fields of the Civil War.

It fell to his lot to deliver a message which necessitated a dangerous ride. He says of it: "Before starting I adjusted myself on the side of my horse farthest from the enemy, and with only one foot holding to the cantle of the saddle and an arm over the neck of the horse exposed, I started at full run. It was only at the street crossings that my horse was under fire, but there I crossed at such a flying rate that generally I was past and under cover of the next block of houses before the enemy fired. I got out safely without a scratch."

Shortly after the close of the war Grant was married. Six years later he resigned from the army and went with his family to live on a farm near St. Louis.[Pg 305] Although he worked hard, he found it up-hill work to support his family, and was eventually compelled by bad health to give up farming. He next tried the real estate business, but without success. At last, his father offered him a place in his leather and hardware store, where Grant worked as clerk until the outbreak of the Civil War.

With the news that the Southern troops had fired upon the flag at Fort Sumter, Grant's patriotism was aroused. Without delay he rejoined the army and at once took an active part in the preparations for war. First as colonel and then as brigadier-general, he led his troops. At last he had found a field of action in which he quickly developed his powers as a leader.

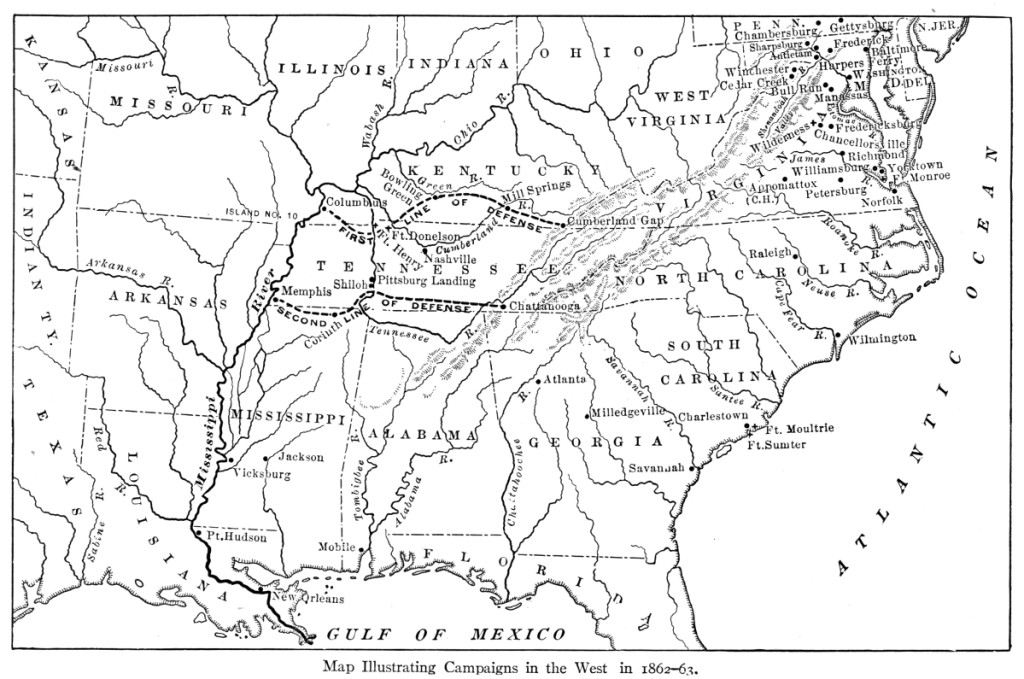

The first of his achievements was the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, the centre of a strong Confederate line of defence, extending from Columbus to Cumberland Gap. At Fort Donelson he received the surrender of nearly 15,000 prisoners, and by his great victory compelled the Confederates to abandon two of their most important strongholds, Columbus and Nashville.

After the loss of Fort Donelson the Confederates fell back to a second line of defence, extending from Memphis through Corinth to Chattanooga. The Confederate army took position at Corinth; General Grant's army at Pittsburg Landing, eighteen miles away. Here, early on Sunday morning, April 6, 1862, Grant was attacked by Johnston, and his men were driven back a mile and a half toward the river. It was[Pg 306] a fearful battle, lasting until nearly dark. Not until after midnight was Grant able to rest, and then as he sat in the rain leaning against the foot of a tree, he slept a few hours before the renewal of battle on Monday morning. With reinforcements he was able on the second day to drive the enemy off the field and win a signal victory.

By this battle Grant broke the second Confederate line of defence. Although the Confederates fought bravely and well to prevent the Northern troops from getting control of the Mississippi River, by the close of 1862 they had lost every stronghold except Port Hudson and Vicksburg. In 1863, General Grant put forth a resolute effort to capture Vicksburg, and after a brilliant campaign laid siege to the city. For seven weeks the Confederate army held out. Meanwhile the people of Vicksburg found shelter in caves and cellars, their food at times consisting of rats and mule flesh. But on July 4, 1863, the day following General Lee's defeat at Gettysburg, General Pemberton, with an army numbering about 32,000 men, surrendered Vicksburg to General Grant. Four days later Port Hudson was captured, and thus the last stronghold of the Mississippi came under control of the North.

General Grant's success was in no small measure due to his dogged perseverance. While his army was laying siege to Vicksburg a Confederate woman, at whose door he stopped to ask a drink of water, inquired whether he expected ever to capture Vicksburg. "Certainly," he replied. "But when?" was her next ques[Pg 307]tion. Quickly came the answer: "I cannot tell exactly when I shall take the town, but I mean to stay here till I do, if it takes me thirty years."

Map Illustrating Campaigns in the West in 1862-63.

Map Illustrating Campaigns in the West in 1862-63. General Grant having by his effective campaign won the confidence of the people, President Lincoln in 1864 made him lieutenant-general, thus placing him in command of all the Northern forces. In presenting the new commission, Lincoln addressed General Grant in these words: "As the country herein trusts you, so, under God, it will sustain you." General Grant made answer: "I feel the full weight of the responsibilities now devolving upon me; and I know that if they are met, it will be due to those armies, and above all, to the favor of that Providence which leads both nations and men."

Early in May, 1864, Grant entered upon his final campaign in Virginia, and while he marched with his army "On to Richmond," General Sherman, in Georgia, pushed with his army "On to Atlanta" and "On to the sea." Both generals were able, and both had able opponents. Grant crossed the Rapidan and entered the Wilderness, where Lee's army contested every foot of his advance. In the terrible fighting that followed Grant's losses were severe, but, with "bull-dog grit," to use Lincoln's phrase, he pressed on, writing to the President his stubborn resolve, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."

It did take all summer and more, for Grant found it impossible to capture Richmond by attacking it from the northern side. He therefore transferred his army[Pg 309] across the James River, and attacked the city from the south; but at the end of the summer Lee still held out.

Nor did Lee relinquish his position until April 2, 1865, when he was compelled to retreat toward the west. Grant pursued him closely for a week, during which Lee's troops suffered great privation, living mainly on parched corn and the young shoots of trees. Aware that the Southern cause was hopeless, the distinguished leader of the Confederate armies, after a most brilliant retreat, decided that the time had come to give up the struggle.

While suffering from a severe sick headache, General Grant received a note from Lee saying that the latter was now willing to consider terms of surrender. It was a remarkable occasion when the two eminent generals met on that Sunday morning, in what is known as the McLean house, standing in the little village of Appomattox Court House. Grant writes in his "Personal Memoirs": "I was without a sword, as I usually was when on horseback on the field, and wore a soldier's blouse for a coat, with the shoulder-straps of my rank to indicate to the army who I was.... General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value—very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia.... In my rough travelling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form.[Pg 310]

THE MEETING OF GENERALS GRANT AND LEE AT APPOMATTOX.

THE MEETING OF GENERALS GRANT AND LEE AT APPOMATTOX.  The McLean House

The McLean House While in the army he seemed to have marvellous powers of endurance. He said of himself: "Whether I slept on the ground or in a tent, whether I slept one hour or ten in the twenty-four, whether I had one meal, or three or none, made no difference. I could lie down and sleep in the rain without caring."

General R. E. Lee.

General R. E. Lee. It need hardly be said that at the close of the war he had a warm place in the hearts of his countrymen. Wherever he went people flocked to see him. But like Washington and Jefferson, he found speech-making most difficult. At one time, in the presence of friends, General Grant's young son Jesse, mounted a haystack and said, "I'll show you how papa makes a speech. 'Ladies and Gentlemen, I am very glad to see you: I thank you very much. Good-night.'" All present were greatly amused except Grant, who was much embarrassed, feeling that his little son's effort verged too closely upon the truth.

Grant was elected President of the United States in 1868, and served two terms. Upon retiring from the Presidency he made a tour around the world, and was everywhere received by rulers and people alike with great honor and distinction.

During his last days he suffered much from an in[Pg 313]curable disease, which became a worse enemy than he had ever found on the field of battle. After nine months' of struggle he died at Mount McGregor, near Saratoga, on July 23, 1885. His body was laid to rest in Riverside Park, on the Hudson, where in 1897 a magnificent monument was erected to his memory. Like Lincoln and Washington, he will ever live in the hearts of his countrymen.

REVIEW OUTLINE

Young Ulysses S. Grant fond of farm work.An instance of his "bull-dog grit."

Grant goes to West Point.

His bravery in the Mexican War.

He tries farming and business.

The beginning of the Civil War.

The battle of Pittsburg Landing.

General Grant captures Vicksburg.

General Lee's surrender.

General Grant's kindness and delicacy of feeling.

His personality.

His tour around the world; his last days.

TO THE PUPIL

1. Tell as much as you can about the boyhood of Grant.2. What can you say of his record in the Mexican War?

3. Give an account of his capture of Vicksburg.

4. Picture the scene of the interview which took place when Lee surrendered.

5. What can you tell about Grant's personality? About his ability as a speech-maker?

6. What traits in Grant's character do you admire?

CHAPTER XXVI

Some Leaders and Heroes

in the

War with Spain

in 1676

Some Leaders and Heroes

in the

War with Spain

in 1676

[1898-1899]

This is no doubt true of all times and countries, but it is eminently true of our own country, whose history is full of striking instances of individual heroism and devotion to the flag. We shall find no better example of patriotic daring than in the late war with Spain—a war which exhibited to us and to the world the strong and manly qualities of American life and character. It seems fitting, therefore, that we should in this closing chapter briefly consider a few of the recent events that[Pg 315] help us to understand what manner of people we have come to be, and what we are able to accomplish in time of earnest endeavor.

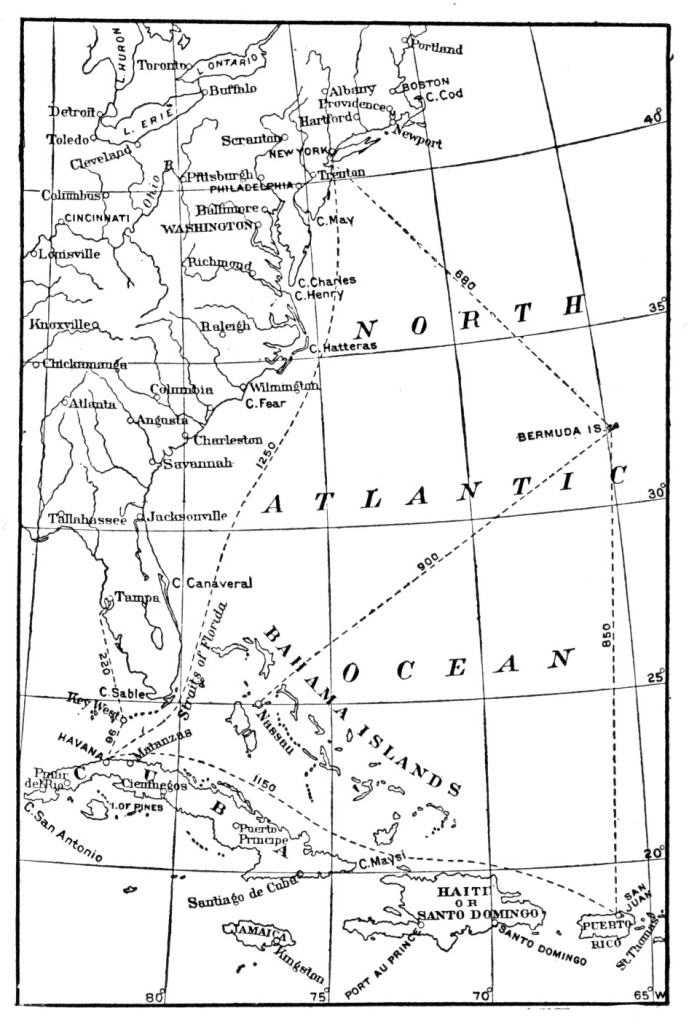

The United States Coast and the West Indies. Distances are given in geographical or sea miles, sixty miles in a degree of latitude.

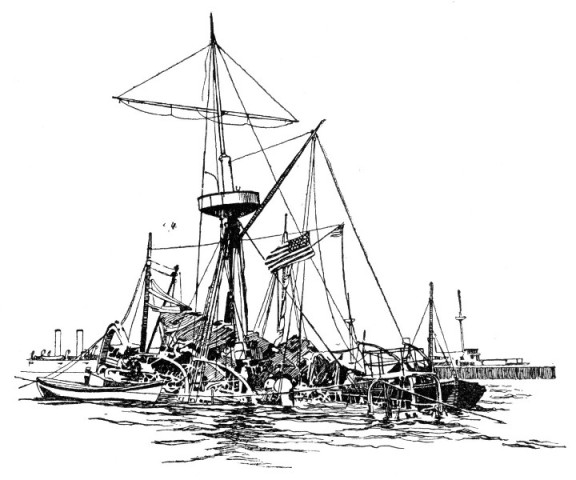

The United States Coast and the West Indies. Distances are given in geographical or sea miles, sixty miles in a degree of latitude. The Wreck of the Maine.

The Wreck of the Maine. But Spain was so stubborn that President McKinley, after trying in every possible way to prevent hostilities, was obliged to say in a message that "the war in Cuba must stop"; and on April 25, 1898, Congress took the momentous step of declaring war.

Our Secretary of the Navy, Mr. Long, lost no time in sending a despatch to Commodore Dewey,—who was in command of an American fleet of six war-vessels at Hong-Kong,—directing him to proceed at once to the Philippine Islands and capture or destroy the Spanish fleet stationed there.

Admiral Dewey.

Admiral Dewey. On the night preceding May 1st our fleet entered Manila Bay. The supreme moment in the life of Commodore Dewey, now in his sixty-second year, had come. He was 7,000 miles from home and in hostile waters. Without even a pilot to guide his fleet as it moved slowly but boldly into the bay, he knew well that he might be going into a death-trap. Two torpedoes ex[Pg 318]ploded just in front of the flag-ship Olympia, which was in the lead, but the fearless commander did not swerve from his course.

Drawn up at the entrance of Bakor Bay, not far from Manila, was the Spanish fleet, protected on either side by strong shore batteries. When about three miles distant Commodore Dewey quietly said to the captain of the Olympia, "If you are ready, Gridley, you may fire." Spanish shells had already filled the air all about the American fleet, but as the Spanish gunnery was exceedingly poor it did little serious damage. During the battle the American fleet steamed forward in single file, the Olympia in the lead. After going for some distance toward Manila the ships swung round and returned, firing terrible broadsides into the Spanish fleet as they passed. Five times they followed the course in this way, each time drawing nearer to the enemy's position, and each time pouring in a more furious and deadly fire.

President McKinley

President McKinley At the end of two hours, it being plain that the Spanish fleet was nearly done for, Commodore Dewey decided to give his tired men a rest. He therefore withdrew his fleet from the scene of battle, and gave his brave sailors some breakfast. Three hours later he renewed the fight, which ended with the destruction of the entire Spanish fleet. Although 1,200 Spaniards were killed or wounded, not one American was killed and only eight were wounded. None of Dewey's war-vessels received serious injury. The battle was a brilliant exhibition of superb training and seamanship on the part of the American sailors, whose rapid and accurate handling of the guns was marvellous.

The people were electrified with joy when the news of the glorious achievement in Manila Bay was cabled to America. On May 9th, Congress voted that ten thousand dollars ($10,000) should be spent in securing a sword for Commodore Dewey and medals for all his men, and President McKinley promptly appointed him a rear-admiral. Before the middle of August an army of 15,000 troops, under General Merritt, was sent to Manila to unite with the fleet under Admiral Dewey in capturing the city. Manila surrendered on August 13th.[Pg 320]

With the destruction of the Spanish fleet at Manila, within a week after Congress declared war, all danger of attack from Spanish war-vessels upon our Pacific coast was at an end. But there was grave fear that the Spanish fleet under Admiral Cervera might attack the large and wealthy cities upon our Atlantic coast. Shortly after the war began, this fleet was reported to have left the Cape Verde Islands and to have directed its course toward Cuban waters.

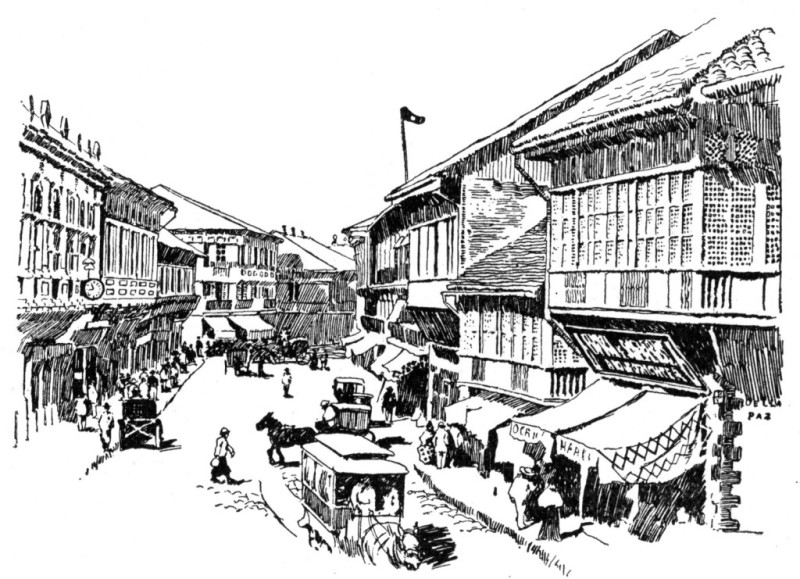

"Escolta," Manila's Main Street.

"Escolta," Manila's Main Street. But the uncertainty did not long continue, for soon it was learned by cable that Cervera had stopped at Martinique, and later at a small island off the coast of Venezuela, whence he had speedily steamed northward toward Cuba. We now know that he went to Santiago harbor, which he thought would prove a good hiding-place while his fleet took on board coal and other supplies. Shortly after Cervera's arrival at Santiago an American fleet under Commodore Schley discovered him, and blockaded the harbor in order to prevent his escape. It was extremely important to keep him "bottled up" there until an American army might come down and capture Santiago and the Spanish army which held the place. This capture accomplished, Cervera would have to fight either in the harbor or out on the open sea. But there was still some anxiety lest he might on some dark, stormy night manage to steal out and make his escape.

One reason why Cervera went into the Santiago harbor was that the entrance was very narrow and well protected by headlands surmounted by batteries. At its narrowest place, the channel was not much more [Pg 322]than a hundred yards wide. If, therefore, the American war-vessels should attempt to enter the harbor they would have to enter in single file, and the foremost one would possibly be blown up by the Spanish torpedoes, many of which were planted in the channel. The sinking of a single vessel in the channel would block the way for all the rest.

With these facts in mind Admiral Sampson planned to obstruct the entrance to Santiago harbor to prevent the Spanish fleet from getting out. Lieutenant Hobson, a young man of twenty-eight, worked out the plan of sinking the collier Merrimac across the channel; and to him the important task of carrying it out was assigned. Torpedoes were so arranged on the sides of the Merrimac that their explosion would shatter her bottom and sink her in the channel.

There was serious difficulty in selecting the small number of brave, cool-headed men who were to accompany Lieutenant Hobson in this perilous enterprise, for several hundred American sailors were eager to go, even though they knew that in so doing they were running serious risk of capture or death. But such was the heroic temper of the American sailors that many of them begged for an opportunity of rendering this loyal service.

On the night appointed for the daring feat, the Merrimac did not get well started before the morning light began to appear in the eastern sky, so that Admiral Sampson recalled the expedition.

After a long, nervous day of waiting, the next morn[Pg 323]ing, June 3d, the Merrimac started off a second time. The vessel moved stealthily forward with its eager, silent crew, but before the place of sinking could be reached the Spaniards discovered her. Suddenly from the forts and the war-vessels in the harbor a storm of shot and shell beat in pitiless fury about the Merrimac. But she pressed forward. When the moment came for her to be swung across the channel Hobson found that the rudder of the ship had been shot away, so that she could not be swung about according to the plan. He therefore had to be content with sinking her along instead of across the channel.

When the torpedoes exploded and she went down, her crew of eight men, struggling for life in the seething waters, managed to reach a float which they had brought with them on the deck of the collier. To this float they clung, hanging on with their hands, for they dared not expose their bodies as targets to Spanish soldiers on land or to Spanish sailors in the launches that were trying to find out what had happened. For some hours Hobson and his men remained in this uncomfortable position, shivering with the cold. At length Hobson hailed an approaching launch to which he swam. He was pulled in by an elderly man, with the exclamation, "You are brave fellows." This was Admiral Cervera, who treated the prisoners, Lieutenant Hobson and his crew, with great kindness. With the rest of the world he admired the courageous spirit of the "brave fellows" who had given so much in the service of their country.[Pg 324]

During the remainder of June, the American fleet kept watch at the harbor entrance. Before the end of the month an American army of 15,000 men was ready to advance through a tropical forest upon the Spanish defences outside of Santiago. On July 1st the Americans made a vigorous attack upon these outworks, and won a glorious victory.

It looked to Cervera as if he might be compelled to surrender his fleet without striking a blow. Although he was likely to suffer defeat in a battle, there was nothing to gain by remaining in the harbor. So he decided to dash boldly out, in a desperate effort to escape. When at about half-past nine of that quiet Sunday morning (July 3d) the foremost Spanish war-vessel was seen heading at full speed out of the harbor, the American sailors sent up a shout, "The Spanish fleet is coming out!" and leaped forward to their places at the guns. As at Manila, the battle was one-sided. The superior seamanship and gunnery of the Americans enabled them quickly to win a victory as brilliant as that won by Dewey and his men. Every Spanish vessel was destroyed, 600 Spaniards were killed, and 1,300 captured. Not one American ship was seriously injured, while but one American was killed and one badly wounded. About the middle of July Santiago and a Spanish army of 22,000 men surrendered to the Americans.

Although this ended the serious fighting of the war, the treaty of peace was not ratified by the United States Senate until February 6, 1899. In accordance with this treaty Spain gave up Cuba and ceded Porto Rico[Pg 325] to the United States; and she also ceded to us the Philippine Islands, in return for which we agreed to pay her $20,000,000.

But some of the most striking results of the war with Spain received no mention in the terms of the treaty. From the beginning of the struggle, Spain doubtless hoped that one or more of the Great Powers of Europe might intervene in her behalf. Some of them, with ill-concealed dislike for the United States, were quite ready to interfere in Spain's interests. But England refused to take any part in the movement. Her friendly attitude toward us in this struggle has done much to bring the two countries into closer sympathy with each other. A reflection of this good-will toward England was especially evident at the time of Queen Victoria's death in January, 1901.

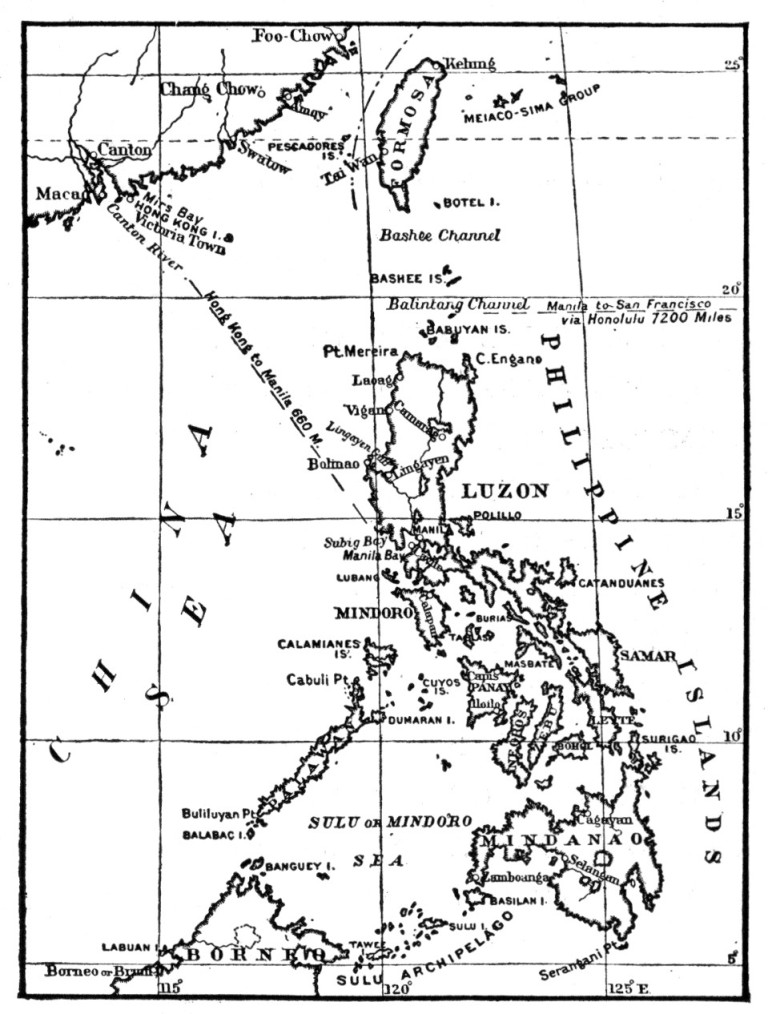

Portion of the Coast of China and the Philippine Islands.

Portion of the Coast of China and the Philippine Islands. REVIEW OUTLINE

Spain's cruel rule in Cuba.The blowing up of the battle-ship Maine.

Commodore Dewey heads his fleet for the Philippines.

The dangerous enterprise.

The glorious victory.

Serious Questions About Admiral Cervera's Plans.

His fleet "bottled Up."

The daring feat of Lieutenant Hobson and his men.

The destruction of Cervera's fleet.

The treaty of peace.

Friendly relations between our country and England.

Closer sympathy and union of the North, the South, The East, and the West.

TO THE PUPIL

1. What is a hero? Whom do you most admire of all the heroes you have read about in this book?2. Why did Commodore Dewey go with his fleet to the Philippines?

3. Imagine yourself with him, and give an account of the battle.

4. What did Lieutenant Hobson and his men do? Impersonating Hobson, give an account of the daring feat.

5. What caused the war with Spain? What were its most striking results?

6. What do you admire in the character of Admiral Dewey? What, in the American sailors in the war with Spain?

7. What do the following dates signify: 1492, 1607, 1620, 1775-1783, 1861-1865, 1898?

[Pg 327]

INDEX

Adams, Samuel, 156;

in public life, 157;

opposes tax on tea, 158-162

Bacon, Nathaniel, 55;

marches against the Indians, 59;

his struggle with Berkeley, 60-62

Boone, Daniel, 222;

goes to Kentucky, 224;

at Boonesborough, 227;

captured by Indians, 230

"Boston Tea Party," 158-163

Braddock, General, 132, 133

Bradford, Governor, 69, 70, 74

Bunker Hill, battle of, 173

Burgoyne, General, 203-205

Cabot, John, 31

Cartier, 103

Carver, Governor, 70, 74-76

Cervera, Admiral, 320-324

Champlain, 104

Civil War, 295, 298

Clermont, the, 250-252

Columbus, Christopher, 1;

at Lisbon, 4;

goes to Spain, 5;

first voyage, 10;

in the New World, 12-15;

other voyages, 17-20

Concord, battle of, 170-173

Continental Congress, 193

Cornwallis, General, 200-203, 206, 207, 214-220

Cortez, 22, 23

Cowpens, battle of, 214, 215

Dale, Sir Thomas, 56

Dawes, William, 167-170

Declaration of Independence, 186, 239

De Leon, 23

De Soto, Hernando, 22;

lands in Florida, 24;

his trials and difficulties, 26-28;

discovers the Mississippi, 29

Dewey, Admiral, 317-319

Dinwiddie, Governor, 128, 131

Douglas, Stephen A., 293, 294

Drake, Sir Francis, 36

Elizabeth, Queen, 33-35

Fairfax, Lord, 124-127

Faneuil Hall, 159, 160

Ferdinand, King, 6

Franklin, Benjamin, 175;

in his brother's printing-office, 176;

goes to Philadelphia, 179;

in London, 181;

"Poor Richard's Almanac," 182;

his great discovery, 184;

"Plan of Union," 185;

in France, 186

French War, Last, 128-133, 136-144

Fulton, Robert, 246;

his boyhood, 247;

invents a torpedo boat, 249;

the Clermont, 250-252

Gage, General, 166, 167

Gates, General, 212

George III., 146-152

Grant, Ulysses S., 302;

his boyhood and youth, 303;

in Civil War, 305-309;

captures Lee's army, 309-311

[Pg 328]

Greene, Nathaniel, 211;

a Quaker boy, 212;

joins the army, 213;

in the South, 214-220

Griffin, the, 108-110

Hancock, John, 165-168, 170

Henry, Patrick, 146;

early life, 148;

opposes Stamp Act, 150;

his great speech, 153

Hobson, Lieutenant, 322

Howe, General, 195-197, 203-205

Hudson, Henry, 105

Hutchinson, Governor, 159-162

Indians, 14, 15, 17, 48, 49

Iroquois, 104-106

Isabella, Queen, 6, 8

Jackson, Andrew, 253;

his boyhood, 254;

goes to Nashville, 256;

conquers the Creeks, 258;

at battle of New Orleans, 259;

as President, 260

James I., 65, 66

Jefferson, Thomas, 234;

at college, 235;

as President, 240;

the Louisiana Purchase, 241-243

Jesuit Missionaries, 106

La Salle, 103;

his plans, 108;

his explorations, 109-112;

his colony, 112;

his assassination, 114

Lee, General, his surrender, 296, 309-311

Lincoln, Abraham, 282;

in Kentucky and Indiana, 283-289;

goes to Illinois, 290;

debates with Douglas, 294;

Emancipation Proclamation, 296;

his assassination, 296

Long Island, battle of, 196

Mckinley, President, 317-319

Maine, the, 316

Manila, 317

Marion, Francis, 217-219

Marquette, Father, 106

Massasoit, 75, 76

Merrimac, the, 319-322

Mimms, Fort, massacre at, 258

Montcalm, General, 138-140, 143, 144

Morgan, General, 214-216

Morse, Samuel F. B., 273;

studies painting, 274;

invents the telegraph, 276-280

Narvaez, 24

Navigation Laws, 58

New Orleans, battle of, 259, 260

Nullification, 260

Old North Church, 167, 168

Old South Church, 159, 161

Olympia, the, 316

Ortiz, 24

Penn, William, 92;

turns Quaker, 94;

his settlement in Pennsylvania, 98;

his Indian treaty, 99;

his country home, 100

Pilgrims, 65-79

Pittsburg Landing, battle of, 305

Pizarro, 22, 23

Plymouth, landing at, 72

Pocahontas, 50, 52

Powhatan, 49-52

Puritans, 65, 81-88

Quakers, 92-101

Quebec, capture of, 142-144

Raleigh, Sir Walter, 31;

in France, 33;

his first colony, 35;

second colony, 37-39;

in the Tower of London, 40

[Pg 329]

Revere, Paul, 165;

on his "midnight ride," 167-170

Sampson, Admiral, 322

Santiago, fighting near, 322-324

Schley, Commodore, 321

Secession, 295

Slavery, 282, 283, 294, 296

Smith, John, 42;

early life, 46;

in Virginia, 47-53;

relations with the Indians, 47-52;

explores New England coast, 53

South Carolina, 261, 262

Stamp Act, 147-151

Standish, Miles, 64;

military leader of the Pilgrims, 68;

explores coast, 69-71;

at Plymouth, 72-79

State Rights, 269

Tariff, 261, 262

Telegraph, the electric, 276-280

Tobacco, 57, 58

Trenton, battle of, 200-202

Valley Forge, suffering at, 205, 206

Vicksburg, capture of, 306

Warren, Dr. Joseph, 167

Washington, George, 116;

at home and school, 117-124;

the young surveyor, 124-127;

his journey to the French forts, 130;

at Great Meadows, 132;

with Braddock, 132;

at Mount Vernon, 189-193;

as General, 193-207;

as President, 208

Washington, Lawrence, 118-121

Webster, Daniel, 264;

his boyhood and youth, 265-268;

his "Reply to Hayne," 269;

his last days, 271

West, Benjamin, 274, 275

Williams, Roger, 81;

goes to Salem, 86;

driven into exile, 88;

his settlement at Providence, 89

Wolfe, James, 136;

his youth, 136;

at Quebec, 138-144

in public life, 157;

opposes tax on tea, 158-162

Bacon, Nathaniel, 55;

marches against the Indians, 59;

his struggle with Berkeley, 60-62

Boone, Daniel, 222;

goes to Kentucky, 224;

at Boonesborough, 227;

captured by Indians, 230

"Boston Tea Party," 158-163

Braddock, General, 132, 133

Bradford, Governor, 69, 70, 74

Bunker Hill, battle of, 173

Burgoyne, General, 203-205

Cabot, John, 31

Cartier, 103

Carver, Governor, 70, 74-76

Cervera, Admiral, 320-324

Champlain, 104

Civil War, 295, 298

Clermont, the, 250-252

Columbus, Christopher, 1;

at Lisbon, 4;

goes to Spain, 5;

first voyage, 10;

in the New World, 12-15;

other voyages, 17-20

Concord, battle of, 170-173

Continental Congress, 193

Cornwallis, General, 200-203, 206, 207, 214-220

Cortez, 22, 23

Cowpens, battle of, 214, 215

Dale, Sir Thomas, 56

Dawes, William, 167-170

Declaration of Independence, 186, 239

De Leon, 23

De Soto, Hernando, 22;

lands in Florida, 24;

his trials and difficulties, 26-28;

discovers the Mississippi, 29

Dewey, Admiral, 317-319

Dinwiddie, Governor, 128, 131

Douglas, Stephen A., 293, 294

Drake, Sir Francis, 36

Elizabeth, Queen, 33-35

Fairfax, Lord, 124-127

Faneuil Hall, 159, 160

Ferdinand, King, 6

Franklin, Benjamin, 175;

in his brother's printing-office, 176;

goes to Philadelphia, 179;

in London, 181;

"Poor Richard's Almanac," 182;

his great discovery, 184;

"Plan of Union," 185;

in France, 186

French War, Last, 128-133, 136-144

Fulton, Robert, 246;

his boyhood, 247;

invents a torpedo boat, 249;

the Clermont, 250-252

Gage, General, 166, 167

Gates, General, 212

George III., 146-152

Grant, Ulysses S., 302;

his boyhood and youth, 303;

in Civil War, 305-309;

captures Lee's army, 309-311

[Pg 328]

Greene, Nathaniel, 211;

a Quaker boy, 212;

joins the army, 213;

in the South, 214-220

Griffin, the, 108-110

Hancock, John, 165-168, 170

Henry, Patrick, 146;

early life, 148;

opposes Stamp Act, 150;

his great speech, 153

Hobson, Lieutenant, 322

Howe, General, 195-197, 203-205

Hudson, Henry, 105

Hutchinson, Governor, 159-162

Indians, 14, 15, 17, 48, 49

Iroquois, 104-106

Isabella, Queen, 6, 8

Jackson, Andrew, 253;

his boyhood, 254;

goes to Nashville, 256;

conquers the Creeks, 258;

at battle of New Orleans, 259;

as President, 260

James I., 65, 66

Jefferson, Thomas, 234;

at college, 235;

as President, 240;

the Louisiana Purchase, 241-243

Jesuit Missionaries, 106

La Salle, 103;

his plans, 108;

his explorations, 109-112;

his colony, 112;

his assassination, 114

Lee, General, his surrender, 296, 309-311

Lincoln, Abraham, 282;

in Kentucky and Indiana, 283-289;

goes to Illinois, 290;

debates with Douglas, 294;

Emancipation Proclamation, 296;

his assassination, 296

Long Island, battle of, 196

Mckinley, President, 317-319

Maine, the, 316

Manila, 317

Marion, Francis, 217-219

Marquette, Father, 106

Massasoit, 75, 76

Merrimac, the, 319-322

Mimms, Fort, massacre at, 258

Montcalm, General, 138-140, 143, 144

Morgan, General, 214-216

Morse, Samuel F. B., 273;

studies painting, 274;

invents the telegraph, 276-280

Narvaez, 24

Navigation Laws, 58

New Orleans, battle of, 259, 260

Nullification, 260

Old North Church, 167, 168

Old South Church, 159, 161

Olympia, the, 316

Ortiz, 24

Penn, William, 92;

turns Quaker, 94;

his settlement in Pennsylvania, 98;

his Indian treaty, 99;

his country home, 100

Pilgrims, 65-79

Pittsburg Landing, battle of, 305

Pizarro, 22, 23

Plymouth, landing at, 72

Pocahontas, 50, 52

Powhatan, 49-52

Puritans, 65, 81-88

Quakers, 92-101

Quebec, capture of, 142-144

Raleigh, Sir Walter, 31;

in France, 33;

his first colony, 35;

second colony, 37-39;

in the Tower of London, 40

[Pg 329]

Revere, Paul, 165;

on his "midnight ride," 167-170

Sampson, Admiral, 322

Santiago, fighting near, 322-324

Schley, Commodore, 321

Secession, 295

Slavery, 282, 283, 294, 296

Smith, John, 42;

early life, 46;

in Virginia, 47-53;

relations with the Indians, 47-52;

explores New England coast, 53

South Carolina, 261, 262

Stamp Act, 147-151

Standish, Miles, 64;

military leader of the Pilgrims, 68;

explores coast, 69-71;

at Plymouth, 72-79

State Rights, 269

Tariff, 261, 262

Telegraph, the electric, 276-280

Tobacco, 57, 58

Trenton, battle of, 200-202

Valley Forge, suffering at, 205, 206

Vicksburg, capture of, 306

Warren, Dr. Joseph, 167

Washington, George, 116;

at home and school, 117-124;

the young surveyor, 124-127;

his journey to the French forts, 130;

at Great Meadows, 132;

with Braddock, 132;

at Mount Vernon, 189-193;

as General, 193-207;

as President, 208

Washington, Lawrence, 118-121

Webster, Daniel, 264;

his boyhood and youth, 265-268;

his "Reply to Hayne," 269;

his last days, 271

West, Benjamin, 274, 275

Williams, Roger, 81;

goes to Salem, 86;

driven into exile, 88;

his settlement at Providence, 89

Wolfe, James, 136;

his youth, 136;

at Quebec, 138-144

FOOTNOTES

[1] The belief that the world was round was by no means new, as learned men before Columbus's day had reached the same conclusion. But only a comparatively small number of people held such a view of the shape of the earth.

[2] The sum sent was 20,000 maravedis of Spanish money.

[3] De Leon discovered this land in the full bloom of an Easter Sunday (1513). In token of the day and the flowers he named it Pascua Florida.

[4] The Huguenots were French Protestants, who were then at war with the Catholics in France.

[5] According to tradition, the Pilgrims, in landing, stepped on a small granite bowlder, since known as Plymouth Rock. The date of landing, December 21, is called Forefathers' Day.

[6] Squanto had been taken to England by some white men in 1614.

[7] Oxford University is composed of a number of colleges. The one Penn attended was Christ Church College.

[8] This war has sometimes been called the Old French War, and sometimes the French and Indian War.

[9] This number is too large. Two millions is nearer the truth.

[10] The other two ships arrived a few days later.

[11] Franklin was one of the three commissioners to make a treaty with England at the close of the Revolution. The two other commissioners were John Adams and John Jay. They were all men of remarkable ability, and their united effort secured a treaty of peace highly favorable to their country. But, as in many other brilliant political achievements in which Franklin took part, his delicate tact was a strong force.

[12] The American battle-ship Oregon was then on her famous trip from San Francisco, by way of Cape Horn, to join Admiral Sampson's fleet.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

1. Images have been moved from the middle of a paragraph to the closest paragraph break.2. Footnotes have been renumbered and moved to the end of the text.

3. Obvious punctuation errors have been silently corrected.

4. The following misprints have been corrected:

"Wahington" corrected to "Washington" (page 190)

"Breeze" corrected to "Breese" (page 273)

"1809-1861" corrected to "1809-1865" (page 282)

5. Other than the corrections listed above, printer's inconsistencies in spelling, hyphenation, and ligature usage have been retained.

End of Project Gutenberg's American Leaders and Heroes, by Wilbur Fisk Gordy *** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN LEADERS AND HEROES ***

No comments:

Post a Comment